Ray Bradbury’s The October Country turns seventy this year, yet its pulse remains as steady as the autumnal drumbeat of dry leaves skittering along an empty road. First published in 1955, this short story collection stands as a testament to Bradbury’s mastery in bending horror, fantasy, and melancholic nostalgia into tales that feel both timeless and eerily prescient. Through these stories, Bradbury captures a universe teetering between the ordinary and the grotesque, where human fears are laid bare like raw nerves exposed to the chilling wind of an eternal October.

Before he became one of the most beloved American authors of the 20th century, Ray Bradbury was a boy enraptured by libraries, circuses, and the quiet horrors lurking in small-town shadows. Born in 1920 in Waukegan, Illinois, Bradbury spent much of his youth feeding on Edgar Allan Poe, H.G. Wells, and the pulpy pages of Weird Tales. Unlike many of his contemporaries, Bradbury never veered toward the hardened edge of realism; instead, he reveled in poetic allegory, blending science fiction, horror, and magic into narratives that shimmered with metaphor and dreamlike dread.

The October Country was a reworking of his earlier Dark Carnival collection, with many stories rewritten and refined. This revision solidified Bradbury’s signature style: an eerie mingling of psychological horror and folkloric mysticism, all underpinned by a profound empathy for the strange and the outcast.

The stories within The October Country are as diverse as they are unsettling. From the surreal carnival nightmare of “The Dwarf,” where a man’s distorted self-image is exploited for the amusement of others, to the aching tragedy of “The Small Assassin,” in which a mother becomes convinced that her newborn baby harbors murderous intent, Bradbury’s narratives crackle with paranoia and poetic sorrow.

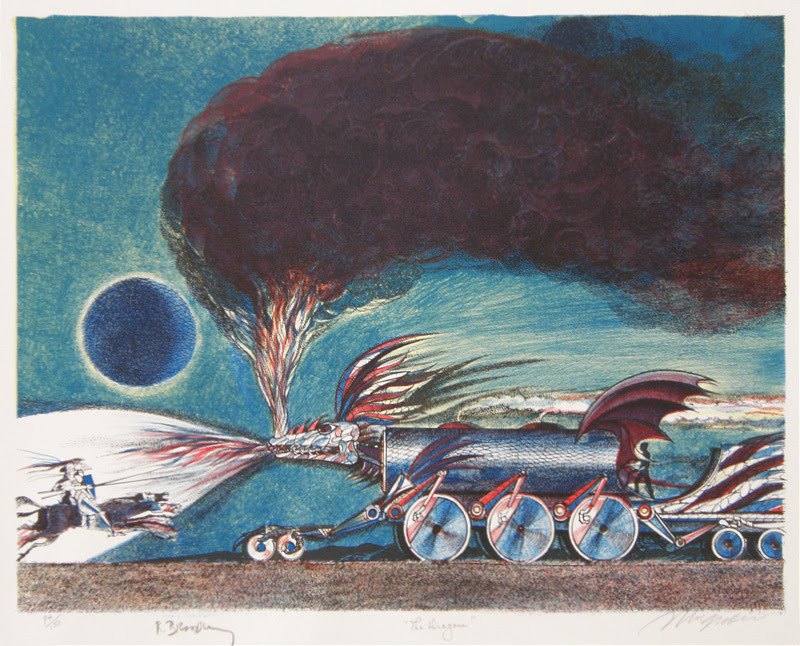

There’s “The Wind,” a tale of an unseen force with an almost sentient malevolence, and “Skeleton,” in which a hypochondriac descends into obsession with his own bones. “Homecoming” presents a hauntingly beautiful family of supernatural beings gathering for a reunion, echoing Bradbury’s lifelong infatuation with outcasts searching for belonging. “The Crowd” chills with its unsettling meditation on the way people gather around accidents—a phenomenon that suggests something sinister beneath the collective gaze of bystanders.

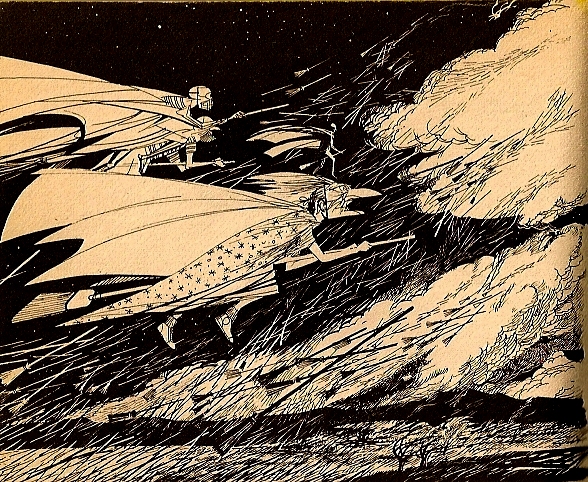

What unites these tales is an uncanny ability to turn the mundane into the macabre. In Bradbury’s world, mirrors distort more than reflections; they reveal hidden horrors. Shadows do not merely stretch but conspire. The wind does not simply blow—it whispers secrets only the doomed can hear.

At its core, The October Country is an exploration of fear—both supernatural and deeply personal. Death looms large in these stories, not just as a shadowy inevitability but as a cruel and sometimes arbitrary force. Many characters grapple with existential horror, from the man obsessed with his skeleton to the doomed individuals who encounter “The Scythe,” where a mysterious farmstead holds dominion over life and death.

Loneliness pervades the collection as well. The titular country is one inhabited by outcasts, eccentrics, and those who fail to fit into society’s neat expectations. Whether it’s the freaks of the carnival, the unseen forces lurking in darkened rooms, or the old woman counting the beats of her own heart in “The Next in Line,” Bradbury’s characters are always on the precipice of existential isolation.

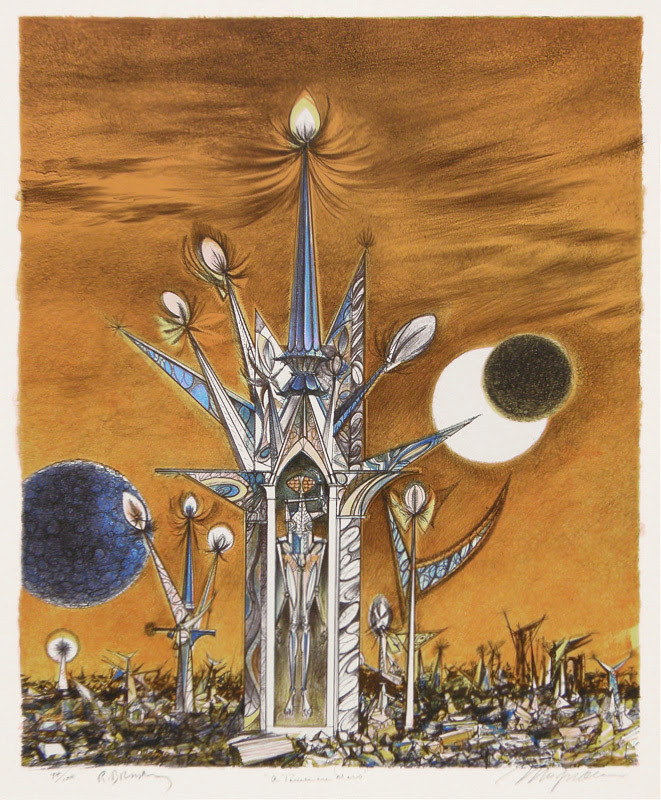

Beneath all this, however, is an undeniable reverence for the weird, the grotesque, and the forgotten. These stories celebrate the eerie beauty of decay, the poetry of the strange, and the quiet dignity of those who live on the margins of the ordinary world.

Bradbury’s use of symbolism elevates his horror beyond simple frights. The stories in The October Country are drenched in metaphor, often using the physical to explore the psychological.

Take “Skeleton,” for example. The protagonist’s obsession with his bones serves as a terrifying reflection of bodily anxiety and self-destruction. “The Jar” transforms a grotesque carnival oddity into a mirror of its owner’s subconscious desires and insecurities. “The Small Assassin” literalizes parental paranoia and postpartum depression, crafting a horror tale that resonates with real-life fears of new parenthood.

Even the very concept of October—a month poised between life and death, warmth and cold, light and darkness—serves as an overarching metaphor for the collection. This is a world forever on the cusp of change, teetering between the known and the unknowable.

What sets Bradbury apart from other horror writers is his lyrical, almost romantic approach to terror. His prose is rich with sensory detail, painting each scene with poetic intensity. Unlike Lovecraft, who reveled in cosmic dread, or Stephen King, who roots his horror in the visceral realism of the everyday, Bradbury writes horror like a melancholic bard spinning ghost stories under a harvest moon.

His dialogue is often theatrical, his descriptions baroque. He is unafraid to slow the pacing for a well-placed metaphor or a lingering moment of eerie beauty. This makes his horror feel dreamlike, as though the reader is drifting through a dark carnival of the subconscious, where reality blurs with nightmare.

Bradbury’s strengths are undeniable: his poetic storytelling, his ability to find horror in the smallest crevices of life, and his profound empathy for outsiders. The stories in The October Country still feel fresh, largely because they tap into universal fears—of loneliness, of change, of the unknown—that remain relevant today.

At times, Bradbury’s prose can be overwrought, his metaphors leaning into the overly ornate. Some stories, particularly “The Watchful Poker Chip of H. Matisse,” feel more like conceptual exercises than fully realized narratives. Additionally, modern readers may find some of his gender dynamics and portrayals of women as limited by the era in which they were written.

Despite these minor criticisms, The October Country remains a hauntingly beautiful collection, one that deserves its place among the great works of horror and fantasy. It is a book that lingers in the mind like the scent of burning leaves. For those who revel in eerie autumn nights, in stories that pulse with strange and melancholic beauty, The October Country is a must-read. As it turns seventy, it proves itself ageless, standing as a landmark in literary horror.

The October Country by Ray Bradbury, published November 16, 1955

Leave a reply to HPLinks #63 – HPL in Korea and Mexico, Horrorbabble’s HPL megababble, Roerich, and more. | Tentaclii Cancel reply