Agustina Bazterrica, an Argentine writer whose reputation has grown internationally due to her searing, dystopian explorations of violence, power, and human nature, has once again delivered a provocative narrative with The Unworthy. Best known for Tender is the Flesh (check out our review), a harrowing dissection of a society that normalizes cannibalism, Bazterrica continues to examine the fragility of morality when faced with oppressive systems. Her work often probes at the intersection of power, religion, and bodily autonomy, crafting visceral and unsettling worlds that force readers into moral contemplation.

In an interview, Bazterrica commented on the purpose of her writing: “I don’t know if literature can really change things, but I do believe it often offers new perspectives on the world. And I’m not interested in creating partisan, moralistic literature. I am interested, though, in the book moving people, asking them questions, making them reflect.” This encapsulates her approach in The Unworthy, where she crafts a world that disturbs, provokes, and demands engagement.

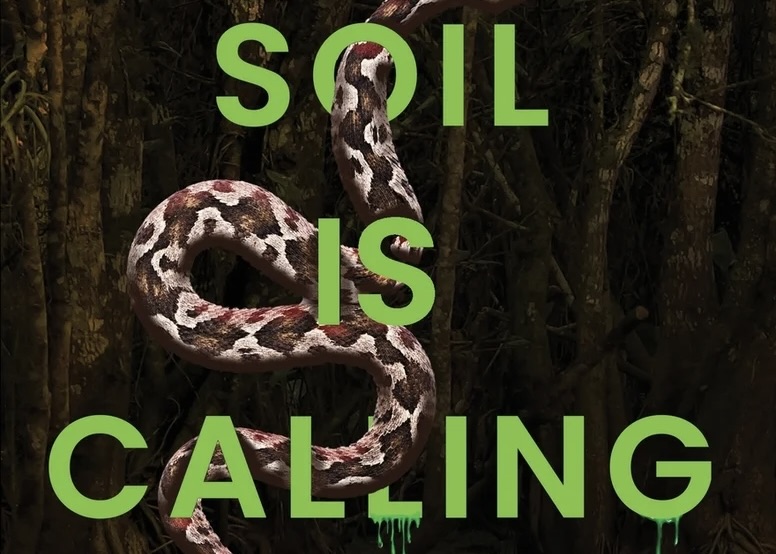

Set in a bleak post-apocalyptic world ravaged by environmental catastrophes and wars over water, The Unworthy presents a society in which a theocratic order governs with absolute control. The story follows a young woman trapped within the House of the Sacred Brotherhood, a secluded religious institution where women are indoctrinated, brutalized, and sacrificed in the name of an enigmatic higher power known only as “Him.” The novel unfolds through the fragmented, diary-like entries of the protagonist, offering an intimate glimpse into a mind both indoctrinated and struggling against its confinement.

The protagonist records the grotesque rituals and ascetic punishments inflicted upon the women under the rule of the severe and enigmatic Superior Sister. A hierarchy of suffering is established, with The Unworthy enduring relentless discipline, while the highest echelons of the faithful—The Enlightened—serve as spiritual conduits between the followers and their invisible deity. As the protagonist’s observations sharpen, her internal struggle emerges, leading her to question the legitimacy of her captors’ authority. Yet, her rebellion is not one of grandiose heroism but of slow, painful realization, tainted by fear and doubt.

Bazterrica’s novel is a meditation on the nature of faith, indoctrination, and control, drawing parallels to historical and contemporary theocracies where women’s bodies become battlegrounds for ideological warfare. Through her protagonist’s constrained existence, she examines the psychology of submission and the slow corrosion of selfhood under systemic oppression.

Religious fanaticism is at the heart of The Unworthy, depicted through rituals of self-flagellation, purification rites, and the cruel elevation of suffering as a means to spiritual transcendence. The faceless deity known as “Him” remains an unknowable presence, reinforcing the asymmetry of power: faith is demanded without proof, suffering is meted out as a divine test, and dissent is met with retribution.

Another key theme is the manipulation of language and knowledge. The protagonist’s diary is both an act of defiance and a means of self-preservation. Her writing becomes an archive of the unspeakable, a resistance against forced amnesia. This recalls Orwellian themes of linguistic control, where the ability to articulate dissent is systematically eroded. Bazterrica has spoken about her fascination with language in previous works, stating, “When you want to impose a new paradigm—like, in this case, eating human flesh[referring to Tender Is the Flesh]—language is fundamental, because language creates reality.” This manipulation of reality through controlled narratives is an ever-present force in The Unworthy as well.

The novel also leans heavily on gothic and dystopian imagery. The convent-like House of the Sacred Brotherhood functions as both a fortress and a prison, its halls steeped in whispered conspiracies and silent suffering. The constant presence of surveillance and the omnipotent yet absent “Him” evoke a sense of inescapable doom reminiscent of The Handmaid’s Tale and Never Let Me Go.

Bazterrica’s prose in The Unworthy is both poetic and grotesque, weaving lyricism into scenes of extreme brutality. The novel’s fragmented, diary-like structure allows the protagonist’s voice to shift from detached observation to suffocating paranoia, making the reading experience deeply immersive. This fragmented style mirrors the protagonist’s fractured reality, where the boundaries between faith, fear, and reality blur.

Her use of sensory detail is particularly striking. The reader can almost smell the decay in the air, feel the chill of the stone walls, and hear the distant echoes of suffering. The novel’s claustrophobic atmosphere is heightened by Bazterrica’s precise, almost surgical use of language. Like Tender is the Flesh, The Unworthy forces the reader into an intimate confrontation with discomfort, using language as a scalpel to dissect themes of bodily control and systemic violence.

One of The Unworthy’s greatest strengths is its ability to sustain tension through ambiguity. Bazterrica refuses to offer easy explanations, leaving much of the novel’s horror to fester in the reader’s mind. Is “Him” truly divine, or just another mechanism of control? Are The Enlightened truly enlightened, or merely the most successful at self-delusion? The novel does not dictate answers, which enhances its haunting impact.

The psychological depth of the protagonist is another highlight. Her oscillation between reverence and skepticism, between complicity and silent rebellion, makes her a deeply compelling character. Unlike conventional dystopian heroines, she does not embody a clear-cut revolution, but rather a more nuanced, hesitant reckoning with truth. The novel’s critique of religious extremism and its parallels to real-world oppressive systems is both timely and universal. By setting the story in an ambiguous, ruined world, Bazterrica sidesteps direct allegory, making her message feel disturbingly applicable across different societies and historical periods.

Bazterrica herself acknowledges the role of discomfort in her storytelling: “Good art, or the art that interests me, is art that keeps bringing up new questions or making me feel uncomfortable. And, for me, that’s a political position.” This discomfort is central to The Unworthy, ensuring that the reader is never allowed to settle into passive consumption.

While The Unworthy is a triumph of atmosphere and thematic depth, its commitment to ambiguity may frustrate. The lack of a traditional narrative arc—where actions build toward a climactic resolution—makes the novel feel like an extended meditation rather than a structured story. Some may find the protagonist’s passive resistance unsatisfying, longing for a more active rebellion against the system… though there is something potentially more realistic and horrifying with Bazterrica’s approach here. Additionally, the relentless bleakness of the novel can feel overwhelming. Unlike Tender is the Flesh, which had moments of sardonic humor to offset its grimness, The Unworthy offers little respite from its oppressive world. While this serves the novel’s thematic intentions, it is certain to alienate those who depend upon narrative momentum or catharsis.

The Unworthy is a masterful, unsettling work that solidifies Agustina Bazterrica’s status as a leading voice in contemporary dystopian fiction. Its exploration of faith, indoctrination, and bodily autonomy is both chilling and thought-provoking, and its prose lingers like a fever dream. Though its ambiguity and unrelenting bleakness may not appeal to all, those who appreciate literary horror and dystopian fiction (The BWAF readership?) will find it a rewarding, if harrowing, read.

Scribner

Published March 4, 2025

Leave a comment