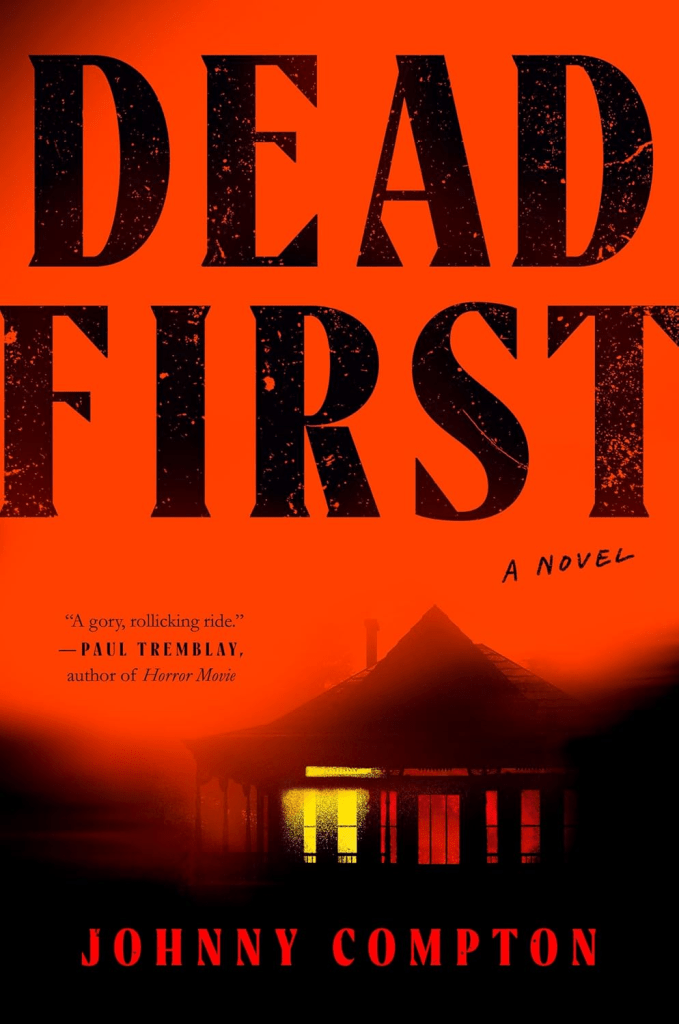

TL;DR: Dead First is a slick, vicious supernatural noir that moves like a blade. Johnny Compton fuses private-eye momentum with occult dread, delivering crisp set pieces, grim humor, and a steady sense that power is the real haunting. It’s propulsive, nasty, and smart about predation, with folklore mechanics that actually bite.

Dead First by Johnny Compton is a supernatural noir that knows exactly how to keep your pulse up while it drags you into something old, ugly, and spiritually uninsured. It’s the kind of book that reads like a fast walk through a bad neighborhood with a loaded backstory, where the streetlights keep flickering and you start noticing the same footprints behind you in every puddle.

The opening posture is pure hard-boiled dread: Shyla Sinclair, a private investigator with a fucked past, gets summoned to billionaire Saxton Braith’s manor, a place described like a floodlit fort that turns into a “dark church” after sundown. That vibe is the book’s operating system. Shyla’s job offer quickly becomes a guided tour through Braith’s secrets, including his eerie confidence in what people are, what they want, and how easy they are to push into the shape he needs. And because this is Compton, the story does not dawdle. The chapters move with that clean thriller hunger, but the horror keeps interrupting with blunt, bodily wrongness: head trauma that does not behave like head trauma, the lingering stink of ritual, and the constant suggestion that “wealth” here is not just money but an occult advantage. A PI gets hired by a terrifyingly well-prepared billionaire, uncovers the machinery behind his survival, and gets pulled into a revenge chain that has been waiting a long time to close its fist.

The writing is a close third on Shyla, with enough interiority to make her fear and fury feel lived-in, but not so much navel-gazing that the engine stalls. Shyla’s skepticism is one of the book’s best tonal choices. She’s surrounded by people who believe in things: a clairvoyant ex (Jinh Gang), a billionaire who treats “ESP” like a résumé bullet, and a whole ecosystem of institutional myth. Shyla’s refusal to immediately worship any of it creates friction, and friction creates heat. The dialogue is punchy without trying to be cute, and Compton has a knack for letting people say the sharp thing, then immediately regret saying it, which is how real conversations work when your nerves are already shredded.

This book moves. Shyla investigates, gets leads, hits walls, gets shoved into the next room anyway. There’s a satisfying escalation ladder: the creepy mansion meeting, the widening circle of Braith’s history, the dive into the Yorktown psychiatric hospital lore, then the confrontation sequences that turn “investigation” into “survive this right now.” Compton times reveals with professional confidence, including the way Braith’s past gets teased through photos, archives, and the stink of Garrett Schramm, a pilot with a service record and a trail of sick stories attached. The mid-book doesn’t sag because Compton keeps swapping your flavor of dread: sometimes it’s procedural, sometimes it’s occult, sometimes it’s pure “this guy is a monster and the system makes room for him.” The downside of that efficiency is that it rarely becomes disorienting. It’s propulsive and clear, not a hallucinatory mind-maze.

Braith’s manor feels like wealth weaponized into architecture, all black windows and doors that read like a dare. The Yorktown material adds institutional rot: rumors of secret chapels, “death tunnels,” neglect, and abuse, all filtered through small-town gossip and family memory that gradually stops feeling like gossip. Compton’s recurring motifs are physical and humiliating: hands, wounds, the body as evidence, and the way “inheritance” can mean money, trauma, or an actual cursed object you cannot return to sender. The book’s grossest images do not feel random. They’re tied to the central idea that power is always eating somebody.

Compton knows when to imply and when to show. The “hand of glory” element is handled with the right mix of folklore explanation and tactile disgust: a severed hand preserved into a glove, worshipped, handled, worn, and eventually used as the story’s ugliest instrument of justice. The scenes in the subterranean hospital spaces hit because the book treats them like a battery, a place where belief has been fed for decades and now it’s hungry again. And the action beats are staged cleanly enough that you can picture them, but not so cleanly that they feel sanitized. When bodies get hurt, it’s not glamorous. It’s splintery, rubbery, panicked.

Johnny Compton broke out in the last few years with The Spite House (his debut novel) and followed it with Devils Kill Devils, and he has also published horror short fiction. He’s been recognized by the Horror Writers Association ecosystem, including a Bram Stoker Award nomination for The Spite House, which places him in the “newer, but already widely clocked” tier of modern horror writers. In interviews around Dead First, he’s talked explicitly about wanting a detective noir nested inside horror, and about anger and revenge as thematic fuel, which tracks with how this book keeps returning to the pleasures and costs of payback. He also positions himself as someone steeped in classic spooky storytelling, but writing in a contemporary register that cares about systems, publicity, and how predators hide in plain sight. Dead First reads like a pivot toward a more overt crime-framework than his haunted-house branding, without abandoning the supernatural dread that got him noticed in the first place.

This is a book about predation dressed as opportunity. It’s about how the powerful collect people, how institutions (money, mental health systems, policing, celebrity-adjacent fame) can become cover stories, and how revenge becomes its own kind of faith when there’s no other structure left that feels fair. The title’s idea of being “dead first” is a worldview: some people treat everyone else’s life as the cheap part of the equation, and their own survival as the only real resource. That entitlement is the true monster, and the supernatural elements function like a cosmic audit. Not a moral lesson, not a neat parable, but a reckoning that has been accruing interest.

The book keeps returning to hands, to touch, to what it means to put your mark on somebody else’s life. Compton doesn’t do the prestige-horror fade-out where you’re left squinting at ambiguity like it’s profundity. He commits to resolution while still letting the aftermath sting, especially for Shyla, whose emotional arc involves letting go of a hatred that has kept her upright. The final sequences are brutal in a satisfying way, and they pay off the folklore you’ve been collecting all book. The plotting is clean, the set pieces are legible, the dread is engineered rather than unknowable. If you want a supernatural thriller that feels like it could be adapted without losing its spine, this is your meal. It’s sharp, nasty, and confident.

Read if “billionaire occult bullshit” is your favorite subgenre and you like your revenge served cold.

Skip if you want your monsters to be abstract metaphors instead of knives with backstories.

Dead First by Johnny Compton,

published February 10, 2026 by G.P. Putnam’s Sons.

Leave a comment