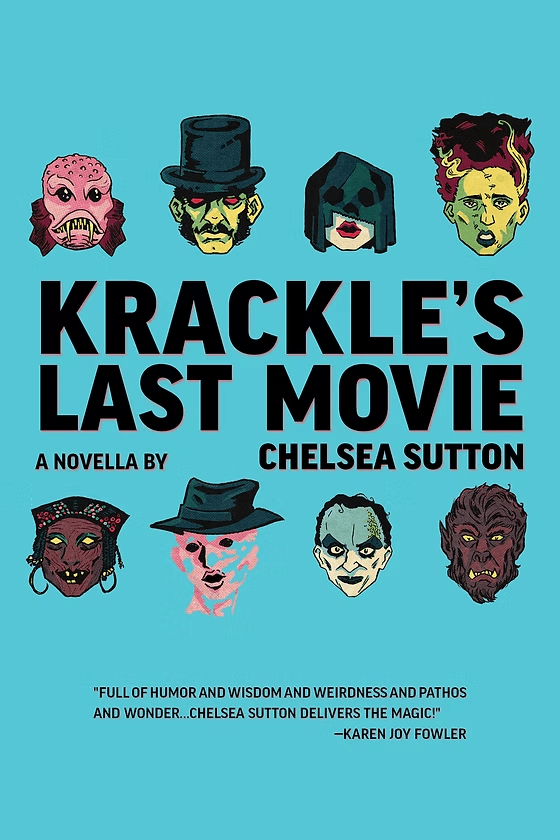

TL;DR: A faux-documentary novella about monsters, missing artists, and the messy ethics of turning somebody’s life into a “project,” it’s funny as hell and strangely tender at the worst possible moments. The voice is sharp, the structure is inventive, and the emotional gut-punch lands even when it’s wearing clown makeup and dripping ectoplasm.

Chelsea Sutton is an LA-based writer and theatre/film maker who describes her lane as “gothic whimsy,” and her fiction has appeared in places like Uncanny and others; she’s also connected to programs like PEN America’s Emerging Voices and the Clarion SF/F workshop. If you’ve run into her flash chapbook Only Animals, you’ve already met the same strengths this novella leans into: transformation, domestic weirdness, and humor that doesn’t flinch when the feelings show up with a knife.

Harper, assistant to underground documentarian Minerva Krackle, is left holding an impossible deadline when Krackle vanishes after filming an interview with “Meggie the Mummy,” a local legend with a body that keeps turning up in parts. With only Krackle’s footage, Harper’s narration, and the chaotic help of Dr. Danger (a ridiculous, oddly loyal tech-and-theatrics freak), Harper tries to finish the film, find out what happened, and survive the gravitational pull of Krackle’s world, where monsters are real and “real” is a moving target.

The big trick is the format. This thing reads like an edited film assembled from clips, interviews, diary-like narration, and the exhausted mental math of someone trying to make a coherent story out of a life that keeps glitching. It’s got that “found footage” feeling without pretending it’s raw, because the whole point is that it’s curated, controlled, and still somehow spiraling. Sutton also nails the monster-as-mirror angle without turning it into a lecture. The creatures are funny, horny, tragic, petty, mystical, and sometimes just kind of…working a shift. There’s a line that sums up the book’s willingness to be crude and true in the same breath: “You have not felt shame until you know what it feels like for mermaids to fuck with you.” That’s the vibe: comedy that opens the trapdoor to something bruised underneath.

Harper’s voice is intimate, observant, and constantly negotiating shame, awe, and anger. The prose loves sensory hooks and weird little systems, like naming colors and treating Time like a tangible substance you can lose, steal, or drown in. Dialogue pops with dry timing, especially when Dr. Danger rolls in like a cartoon villain who, irritatingly, keeps being right about emotional things. The pacing is nimble because the “clip” structure lets Sutton jump years, locations, and monsters without losing momentum, and then suddenly slow down when it matters, like when Harper reveals what it meant to grow up treated as a problem to be cut away: Harper remembers their parents using pruning shears and home-grown medical advice to remove wings over and over. It’s horrifying, but it’s written with restraint, which makes it hit harder.

Under the monster glitter, this is about self-erasure and the brutal little bargains we make to be allowed to exist. “Normal” is framed as a costume with seams that split, and the horror machinery is all about bodies that will not stay edited: wings regrow, identities resurface, the past refuses to stay buried. There’s also a quiet theme about art as both rescue and exploitation. Krackle’s lens is loving, but it’s still a lens, and Harper has to decide whether finishing the film is devotion, self-defense, or just another kind of disappearance. It leaves you with an itchy question that sticks under your skin: what part of yourself have you been trimming down so long you forgot it was yours?

As a debut novella, it swings like someone who’s been building this universe in shorter work and finally got to let it sprawl in a bigger container. It sits in that sweet spot where contemporary weird horror is heading: not “elevated,” not ironic, just emotionally literate and unafraid to be bizarre, tender, and profane in the same scene.

A smart, weird, big-hearted little nightmare that turns the camera back on the viewer and asks what the hell you think you’re doing when you watch someone bleed for a story, then closes on Harper stepping into the public with those wings finally unhidden.

Read if you crave mockumentary structure, archival vibes, “clips within clips” storytelling; monsters treated like people, not plot coupons; grief and identity horror served with a filthy joke and a soft hand.

Skip if you need clean answers and tidy mythology; straightforward linear plotting without format play; zero body-horror-adjacent discomfort around cutting, regrowth, and flesh.

Krackle’s Last Movie by Chelsea Sutton,

published February 10, 2026 by Split/Lip Press.

Leave a comment