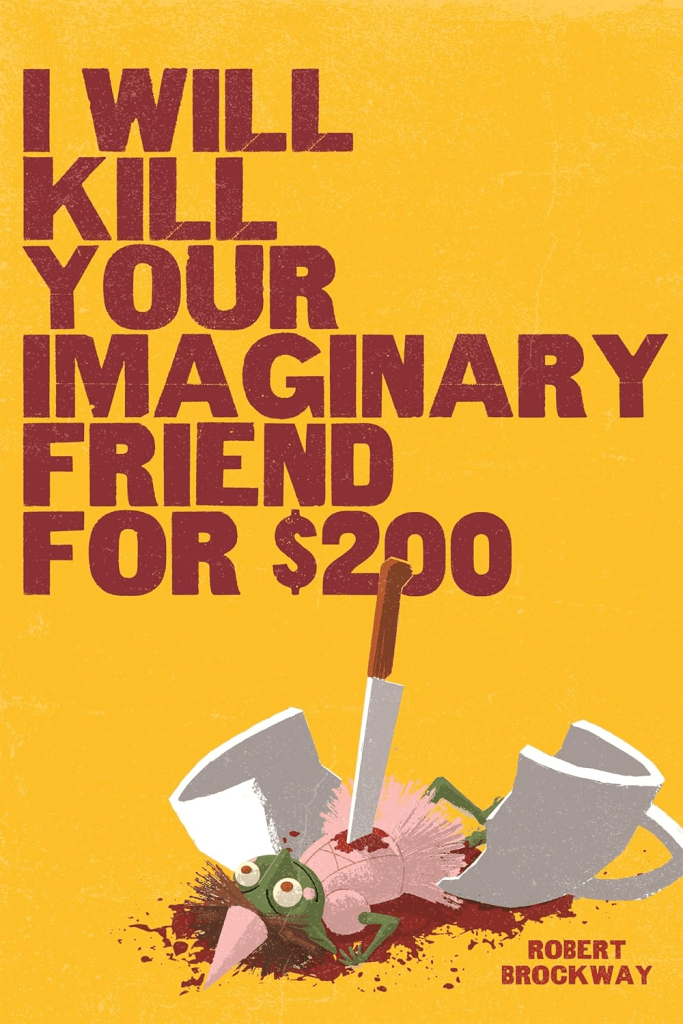

TL;DR: A gig-economy horror gut-punch where “imaginary friend” mythology gets weaponized into a full predator ecosystem of cords, bonds, and hunger that feels freakishly specific. It’s inventive, grotesque, and mean in the smart way, taking a bar-joke premise and turning it into a filthy little nightmare that sticks to your ribs.

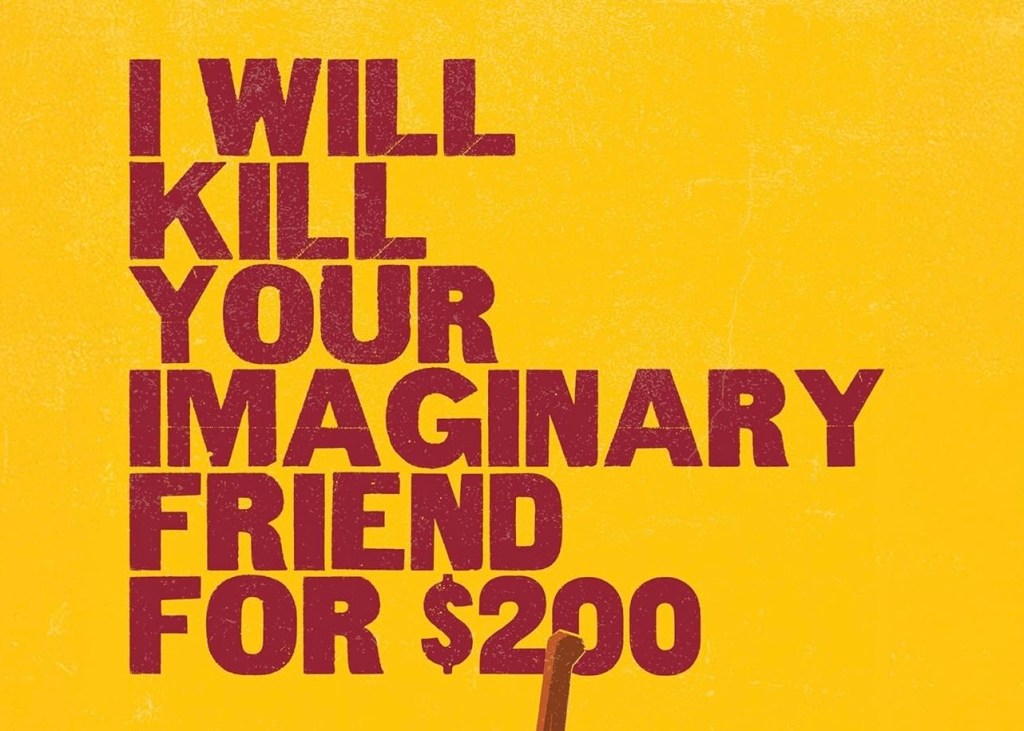

This book opens with the kind of premise that sounds like a joke you tell at a bar and then you realize you are laughing because you are scared. A broke adult in a rain-soaked city takes gigs killing the imaginary friends that never properly died. Not exorcising, not therapizing, not “helping you make peace.” Killing. For two hundred bucks. It is the perfect gig-economy nightmare, a service economy for the things we used to survive childhood, now grown teeth and predatory instincts and a Yelp-ready business model.

And Brockway actually commits. He does not turn it into a cute high-concept romp where the imaginary friend is a wacky mascot who learns a lesson. He makes the IF ecosystem feel like a food chain, and he keeps dragging it back to the same ugly truth: loneliness is a resource, and something is harvesting it.

The story’s main spine runs through Ivan, a man who looks like trouble because he is trouble, and because being visibly “unsafe” is part of how he stays safe. His work puts him in proximity to children without ever letting you forget why that is terrifying. He is careful, paranoid, and deeply uninterested in hero narratives. He is also, crucially, not a blank cool-guy. He carries his own history, his own internal cord to something he cannot quite release, and Brockway uses that to keep Ivan’s chapters from becoming procedural monster-of-the-week. You feel the moral corrosion. You feel the hunger for cash. You feel the fatigue of doing one more job because rent is not a metaphor.

Running counterpoint is Kay, eight years old, mothered by Mack in a world where money is always the third person in the room. Kay’s imaginary friend, Eddie Video, is a loud, prank-happy answer to silence, and the book is smart about how “silence” is not neutral for a kid. It is a threat. Eddie arrives like relief, like noise you can hold onto, and Brockway lets that sweetness exist long enough to hurt when it curdles.

Kay’s home life and Ivan’s gig-work start as separate tracks, then converge as the reality of imaginary friends is revealed to be bigger and older and meaner than either of them understands. Along the way, the novel braids in other voices and timeframes that show how IFs form, how they attach, and what happens when attachment becomes a weapon. The endgame pivots into a full world story, with rules around cords and bonds, and a predator logic that treats children as both home and pantry.

Brockway builds tension by letting the reader learn the rules one bruise at a time. Imaginary friends are not generic ghosts. They are born from a particular recipe of need, and once they exist, they obey a physical-emotional infrastructure: cords, bonds, proximity, hunger, and the terrible fact that love is not always protective. The horror is often choreographed through pursuit and containment. An IF can be tethered and furious, stuck at the end of its cord like an animal on a chain. Or it can be unbound, moving through spaces it should not be able to move through, and that’s when the story gets genuinely fucked. The best sequences feel like watching a children’s TV character sprint across the edge of your vision in a mall window, except the joke is that it is not for children anymore.

Voice and POV are one of the book’s gambles. It is not a single clean lane. You get close third that hugs Kay and Ivan, but you also get other perspectives and timeframes that function like myth fragments and case studies. When it works, it makes the world feel deep, like IFs are not one weird thing happening to one family, but a shadow industry embedded in decades of lonely kids. When it wobbles, it is because the book is juggling a lot of tonal ingredients: grim gig-economy realism, childlike whimsy, and late-stage grotesque violation. There are moments that flirt with “this could be a slick streaming pitch,” then Brockway yanks the camera back into the muck and reminds you he is not trying to sell you a fun ride. He is trying to make you uncomfortable.

Chapters have momentum. Scenes end with pressure still in the room. The reveals are timed so that you get enough information to worry, then just enough to realize you were worrying about the wrong part. There is some structural looseness in the middle where the braid of voices can feel like it is widening rather than tightening, and a few beats repeat the same emotional note (desperation, panic, scramble, repeat). But the later material earns it by turning that sprawl into a larger map. The book becomes, very deliberately, about systems of predation, not just one scary friend.

Character work stays grounded in motive. Kay’s need for noise, for attention, for a buffer between her and adult stress, is painfully believable. Mack reads like a parent trying to do math with a broken pencil while the room is on fire. Ivan is the standout because he is both predator-adjacent and protective, capable of violence and also capable of care that costs him something. Dialogue lands because it is not trying to be charming. It is transactional, defensive, occasionally funny in the way people are funny when they are trying not to cry.

Robert Brockway came up writing in comedy and internet culture, including as a senior editor and columnist at Cracked, and you can feel that background in the book’s willingness to take an absurd premise seriously without sanding off the bite. He has also written across genre lanes, including horror and punk-rock urban fantasy, with titles like Carrier Wave and the “Vicious Circuit” novels (The Unnoticeables, The Empty Ones, Kill All Angels). That genre elasticity shows up here as a confidence with tonal collision: childhood whimsy beside bodily violation, jokes beside dread.

Imagery and setting do a lot of heavy lifting. Portland’s rain becomes texture and pressure, a constant reminder that the world is wet and cold and not interested in your problems. The book also nails the visual language of children’s media, not as comfort but as camouflage. Bright characters, simple shapes, a smile that is too wide. Brockway keeps returning to the body as a site of horror, not just gore, but the idea of the self as something that can be invaded, rewired, corded, harvested. The late-stage stuff is where the novel becomes truly mean in a smart way, with body and psyche violations that feel bespoke to this mythology, not generic “things get gross because horror.”

The novel is about exploitation, but not in the abstract. It is about how desperation creates markets, how loneliness gets monetized, how childhood coping mechanisms can become adult liabilities, and how predators love a system that lets them call hunger “need.” It is also, quietly, about parenting under capitalism: the way a kid’s imagination becomes both refuge and target when adults are too exhausted to be present.

If you want a perfectly elegant, single-voice novel that never risks tonal collision, this might feel messy. If you hate the idea of childhood iconography being used for grotesque horror, hard pass. But if you like high-concept horror that actually follows through, that takes a ridiculous hook and turns it into a specific, nasty ecosystem with rules, consequences, and a moral hangover, this one fucking rocks.

Read if the phrase “gig-economy exorcist for imaginary friends” makes you laugh and then immediately feel worse, in a good way.

Skip if you prefer dread that’s subtle and atmospheric over “late-stage grotesque” endgame mechanics.

I Will Kill Your Imaginary Friend for $200 by Robert Brockway,

published January 27, 2026 by Page Street Horror.

Leave a comment