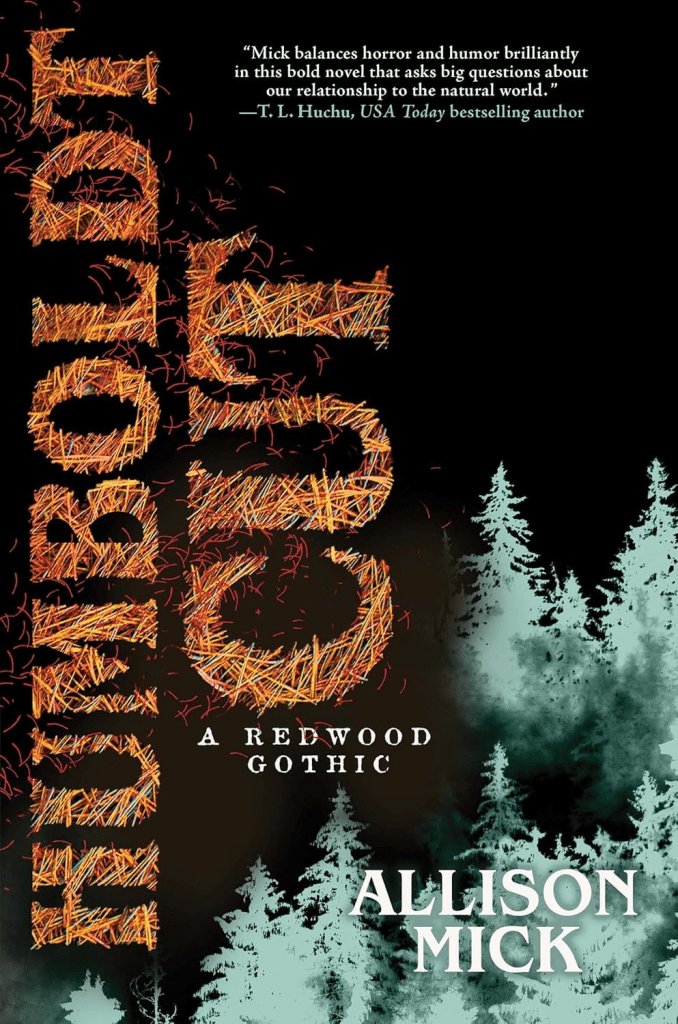

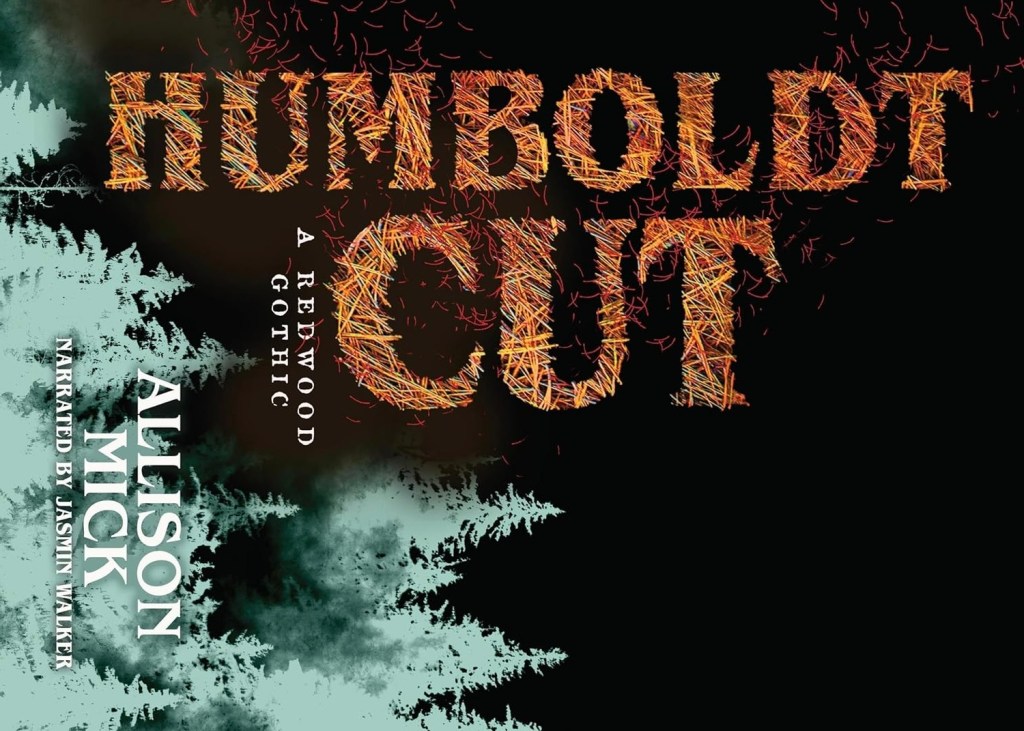

TL;DR: Humboldt Cut is a lush, death-haunted eco-horror road trip into the redwoods where grief, family rot, and the land itself start taking votes on who gets to stay human. It lands hard on atmosphere and sustained dread, with a nasty creature concept and real bite, even if some late-game scaffolding feels familiar and a little too “genre mechanisms, engage.”

Allison Mick comes out of comedy and animation, and you can feel it in the timing, the side-eye, and the way she’ll drop a killer line right when you’re bracing for the next awful thing. She’s Los Angeles–based, with roots in the San Francisco/Oakland comedy scene, and her writing has shown up in outlets like Reductress and The Hard Times (among others). Humboldt Cut is positioned as her debut novel, and it reads like somebody who’s been sharpening voice for years finally decided to point it at the forest and pull the trigger.

Jasmine Bay, a psychiatric nurse in the Bay Area who is running on fumes and bad brain weather, heads back up to Humboldt County for her godmother Aunt Gin’s funeral, riding north with Henry Savage, a coworker whose crush is obvious enough to file as workplace documentation. Up in Redcedar, she reconnects with her estranged brother James and his pregnant wife, Tilly, and the trip instantly turns into a pressure cooker: old resentments, a town that feels like it’s watching, and a surrounding redwood wilderness that does not give a single fuck about human boundaries. Then James goes missing and the woods start looking pretty damn sinister, pushing Jasmine toward a family legacy that is not just “unpleasant history,” but something alive and hungry.

This book absolutely nails the feeling of driving into a place that is gorgeous, wrong, and fully capable of swallowing you. Mick gets the redwoods as an oppressive cathedral, a “roof on the world,” not in a precious nature-writing way, but in a “cool, now you’re trapped” way. The creature work is the other big flex: the barkers are a specific kind of nightmare, camouflaged as the forest’s own deformities, sliding between botanical and predatory with a body logic that is just alien enough to make your skin itch. When they show up hairless and slick and “covered in rusty leopard spots,” it’s not just a monster entrance, it’s a thesis statement: the land is wearing violence like patterning. And Mick keeps finding gross, memorable little set-pieces that feel like local legend turned lethal, like the roadside tourist kitsch moment that goes from funny to “oh shit” in a blink.

“There are things worse than death. Being killed is nothing against being stolen from one’s home. To drag it away and sell it and rub antimicrobial agents on it and dip it in plastic so it can never, ever rot. My body is thieved from me, carried away piece by piece…”

The writing has a muscular, modern snap, with a comedian’s sense of escalation. Mick loves specificity, the kind that makes a scene tactile: pollen, bark texture, the weirdness of clear-cuts, the social friction of a small town that has its own rules and grudges. She builds dread through accumulation rather than cheap jump-scares, letting the woods feel subtly “off” before the outright violence arrives. The POV and timeline play also do real work. You get forward momentum from Jasmine’s present-tense crisis, but the story’s deeper horror is generational, braided into the landscape and into what people choose to ignore until it eats them. There are moments where the engine edges toward familiar horror beats (the local “weird church,” the town elders with secrets, the ancestral ledger coming due), but the voice usually keeps it sharp and emotionally pointed instead of generic.

This is a grief book disguised as a monster book, and it’s also a book about inheritance that refuses to be sentimental about it. The forest’s regenerative logic is beautiful, but Mick keeps showing how “life feeding death feeding life” can become an ideology people use to justify cruelty, sacrifice, and control. There’s also an ugly, effective current about environmental destruction and who pays for it, not in a preachy way, but in a “the land remembers, and it’s done being polite” way. When you’re done reading, you might just wake up with redwood needles in your teeth, not totally sure you got them all out.

“An entity so large as to be rendered faceless, stripped of individuality, becoming one of those things that are so big we have no choice but to call them ‘places,’ a forest rather than a tree.”

As a debut, this lands in that sweet spot where the voice feels fully formed and the thematic ambition is bigger than the plot machinery, in a good way. Publisher copy has floated comps like Annihilation and The Only Good Indians, and while comps are always a little bullshit, the vibe checks out: the landscape is a character, and the horror is personal, cultural, and bodily all at once.

Lush, death-haunted eco/landscape obsession with real atmosphere and bite; it sustains dread like a champ, even when it leans on familiar genre scaffolding.

Read if you crave eco-horror with real atmosphere and a mean creature concept; small-town dread, family baggage, and “the woods have opinions” energy; dark humor undercutting the terror without defanging it.

Skip if you need clean heroes and uncomplicated family dynamics; a purely subtle horror novel with minimal on-page brutality; your eco-horror to be metaphor-only, no monster delivery.

Humboldt Cut by Allison Mick,

published January 27, 2026 by Erewhon.

Leave a comment