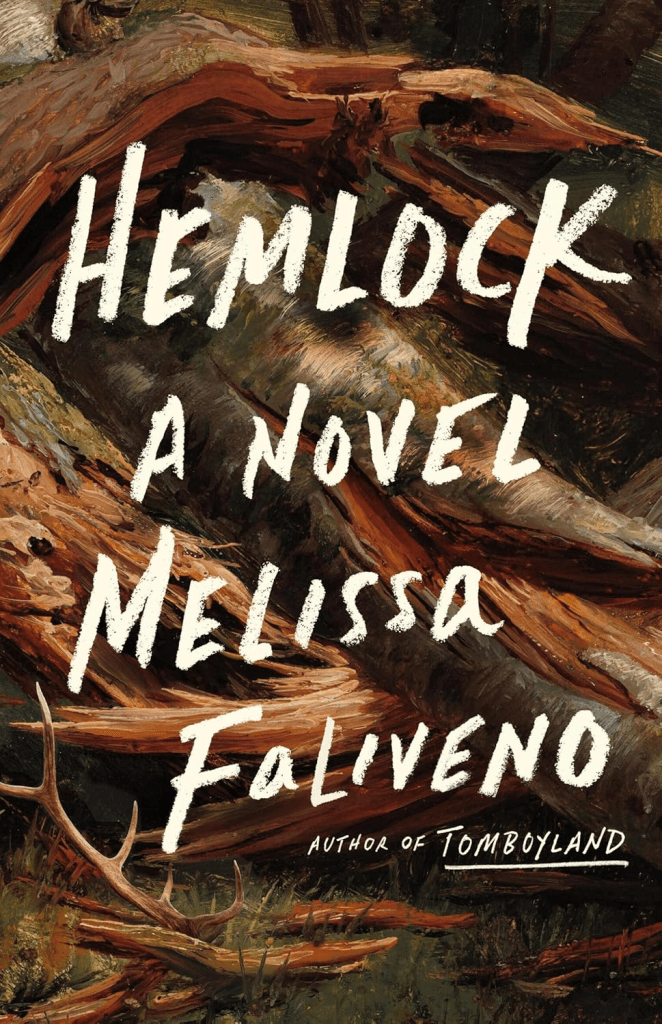

TL;DR: Hemlock is crisp, readable, and tense, running on that deliciously reliable engine where someone returns to a remote place, thinks they’re fixing a house, and instead gets slowly unstitched by grief, booze, and whatever the fuck lives in the trees. It lands more often than not, but it stops just short of going fully fucked up BWAF-banner savage.

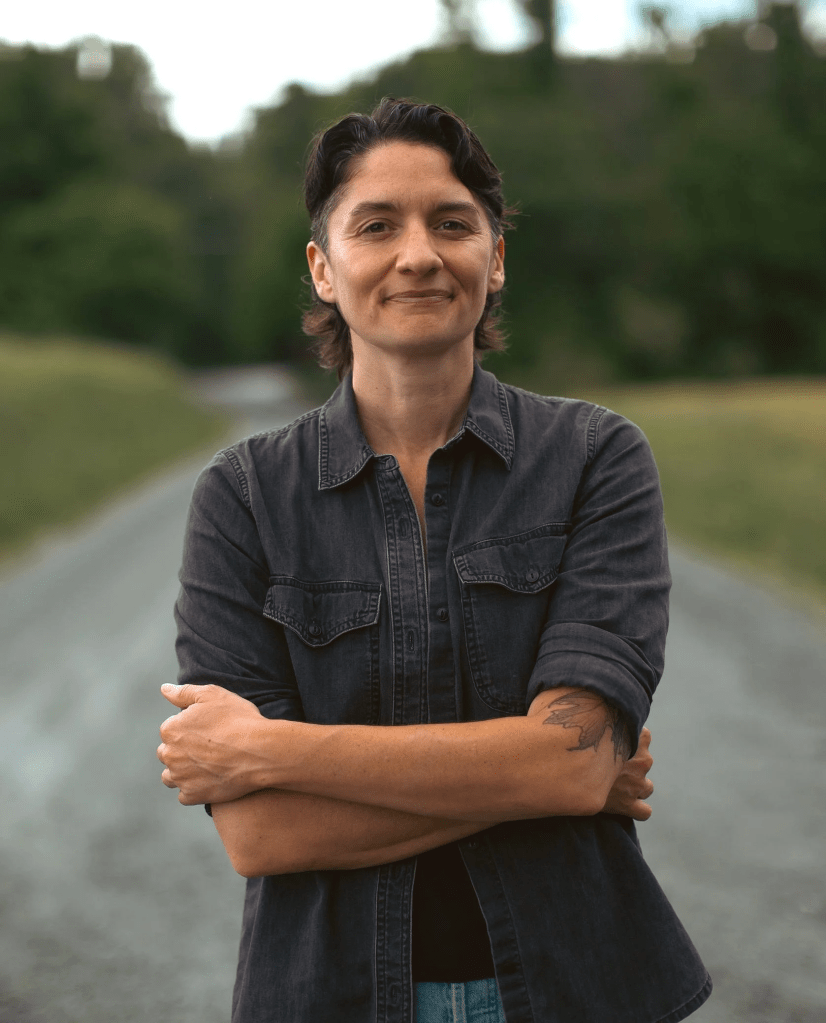

Melissa Faliveno comes to fiction from nonfiction and editing, and you can feel that control in the sentences. She’s the author of the essay collection Tomboyland and has worked as a senior editor at Poets & Writers; she also teaches creative writing (including at UNC-Chapel Hill and Vermont College of Fine Arts). That resume matters here because Hemlock reads like somebody who knows how to pace a scene, land an image, and tighten a paragraph until it squeals.

Sam, living in Brooklyn, drives back to her family’s cabin deep in Wisconsin’s Northwoods, arriving at night with the dark pressing in like a physical thing. She tells herself she’s here for a practical mission: repair the place, clear it out, sell it, and get her father unstuck. But the cabin is where her mother went for a walk and never came back, as if the woods swallowed her whole. Sam is also carrying fresh wreckage of her own, including a relationship shaped by tenderness and loss (Stephen, Monster the cat, the life she is trying to keep from collapsing). Out here, the obstacles are not just rot and repairs. It’s the locked basement door, the local lore, the sense of being watched, and the creeping suspicion that “fixing the cabin” is actually the cabin fixing her.

The best thing Faliveno does is turn familiar horror furniture into emotional ammunition. A locked basement door should be a cliche, but she writes it with such lived-in dread and self-awareness that it feels like your brain doing that late-night inventory of every true-crime nightmare you ever swallowed for fun. The cabin isn’t a haunted house in the theme-park way. It’s a place weighted with absence, a grief object, a working-class artifact built by a father who believed naming something was a form of love. And then she threads in the double-meaning of “hemlock,” both tree and poison, with a scene where Lou-Ann riffs on Macbeth and Socrates, basically handing Sam a bouquet of doom wrapped in literature. There’s also a killer recurring vibe of the Northwoods as something ancient, storied, and hungry, where people vanish and the land does not apologize.

“It was a place of many names. To the locals, though, it was known only as the Northwoods.”

The prose is clean but not sterile. It’s got that sharp sensory edge: rot-sweet air, musty rooms, the woods sounding “loud” in silence, the sky full of stars that make the city feel like a bad dream. Faliveno’s biggest strength is momentum. Chapters come quick, and she uses repetition like a spell, especially around addiction. The relapse sequence, starting with “It started with a beer,” hits like a trap snapping shut, with Sam narrating her own rationalizations while the book calmly tightens the rope. The voice is intimate and unsparing, and the horror is often psychological first, supernatural second, which is exactly how it should be for this story. The downside is that when it’s time to go full clawing-at-the-wall bonkers, Faliveno often chooses restraint. That’s tasteful, sure, but sometimes you want the novel to stop being polite and start being a fucking problem.

Two big threads linger: grief as a geography, and addiction as a haunting. The woods become a physical map of what’s missing, especially with the mother’s disappearance hovering over every task Sam does to “set things right.” And alcohol functions like the book’s most reliable demon, seductive and familiar, with sobriety framed as something Sam has to rebuild daily in a place designed to make you disappear. The aftertaste is damp pine and dread, plus that specific next-day question: if you go back to the place that broke your family, are you reclaiming it, or volunteering to be swallowed too?

“It started with a beer. Just one beer, on a warm night, not long after she arrived. She hadn’t planned it.”

As Faliveno’s debut novel after Tomboyland, Hemlock feels like a genre vehicle built to carry the same obsessions: home, identity, class, the Midwest, the body as a battleground, and the way “nature” can feel both holy and predatory. It sits in the queer Gothic lane of “return-to-origin-and-it-bites,” and it does it with enough craft that you can hand it to a mainstream reader without apologizing for it.

A tight, tense, satisfying descent where the cabin breathes and the bottle whispers, but it holds back just enough that it never becomes the full-on feral nightmare it keeps daring itself to be.

Read if you want “cabin-in-the-woods” horror with real emotional bruises and working-class texture.

Skip if you hate relapse narratives or fiction that sits in messy interior space for long stretches.

Hemlock by Melissa Faliveno,

published January 20, 2026 by Little Brown.

Leave a comment