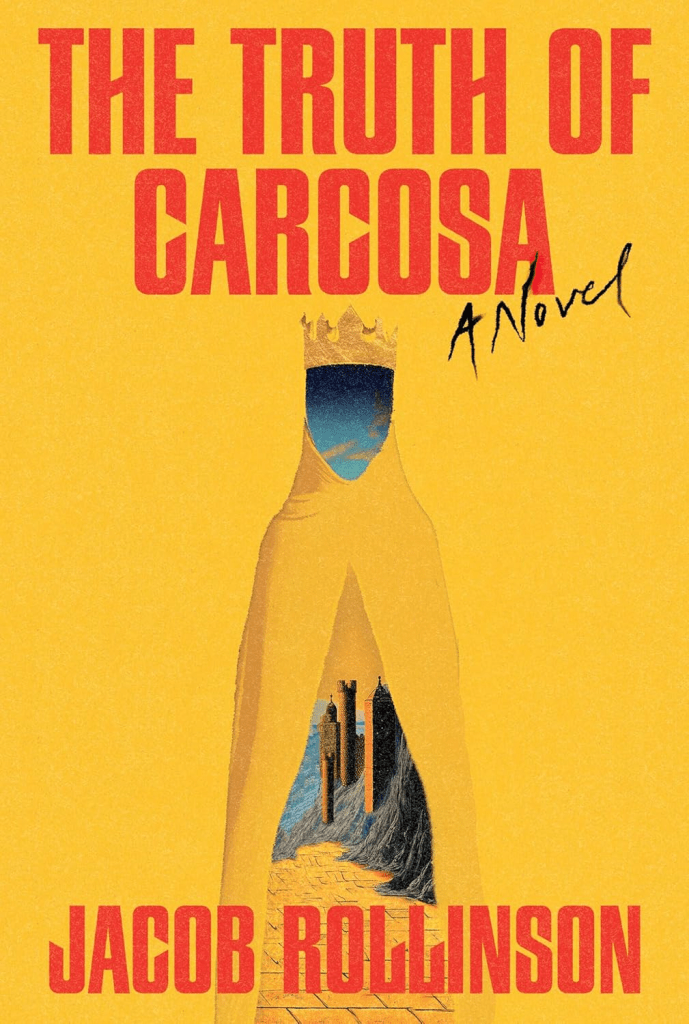

TL;DR: Rollinson takes the “evil book” premise and actually makes it feel dangerous again, not just a cute bookshelf creepypasta. This is a jittery, brainy, occasionally hilarious spiral about archives, state violence, and the unbearable itch to break out of your own skull and finally mean something to someone else. It lands, hard, even when it’s being a weird little freak about it.

Jacob Rollinson is, fittingly, an academic librarian with a creative writing PhD, and you can feel that whole “I have handled strange paper in cold rooms and it has handled me back” energy in every page. He’s published shorter work in lit venues, and this book reads like the moment his interests snap into a bigger, more confident shape: cosmic dread filtered through institutional language, bureaucracy, and the dark comedy of people clinging to procedure while the world liquefies around them.

Our POV is Sol, a man trying to stay sober in a country that’s coming apart at the seams. He falls in with Scottie and Judith Bea as they chase a suppressed manuscript connected to an exiled author, a book so toxic it was meant to be erased. The hunt drags them from grimy city danger into the supposed safety of Greenwood Community, and then right back out again, because safety is always conditional and people get real shitty when they’re scared. A denunciation note about a “Cannibal House” and rumors of skin-changing injections pull them into the orbit of militias, corporate enforcers, and an encroaching something that doesn’t give a damn about human rules.

The book keeps switching the lens you’re looking through, like it’s daring you to keep your footing. A burned-out living room becomes an archaeological dig site, and the plot literally coughs up its own haunted paperwork: a sealed folder containing a “Special Report” and a thick slab of correspondence, turning the novel into a nested dossier that feels both bureaucratic and cursed. It’s a great trick because it makes the reader do the same thing the characters are doing, digging through artifacts, trying to figure out what’s real, what’s propaganda, what’s cope, and what’s infection.

Rollinson also nails the specific modern terror of institutions going feral. There’s a killer scene where a UN-branded “fact finder” shows up and everyone performs order while quietly admitting, basically, nobody’s in charge. The horror isn’t just the cosmic stuff. It’s the way authority keeps changing uniforms, rebranding itself as “procedure,” and demanding obedience while failing to protect anyone.

And then there’s the philosophical hook that gives the dread real meat: loneliness as a structural feature of language, the idea that most of what matters inside you can’t be fully transmitted to anyone else. The “report” sections frame it as loneliness being baked into communication itself, and the novel uses that as both thesis and curse. When the narrative pivots into the claim that “True Communication” might be possible, it doesn’t read like a gothic flourish. It reads like the relapse thought at the edge of a bad night, the moment your brain goes: what if the impossible fix is real though? That is such a smart way to modernize the Carcosa mythos. The King in Yellow is not just a spooky monarch in the distance. It’s the promise of finally being understood. Which is, in human terms, the most dangerous drug imaginable.

Stylistically, this thing is a smartass and I mean that as a compliment. It can do crisp, propulsive paranoia in the “regular” chapters, then turn around and give you these cool, controlled archival passages that feel like someone trying very hard to sound sane while their internal weather turns apocalyptic. The sentences have a clipped, slightly formal bite when they’re in report-mode, and a more breathless physical panic when Sol is moving through spaces where the geometry feels wrong. It’s not purple. It’s not minimalist. It’s that delicious middle: lucid, detailed, and increasingly untrustworthy in a way that makes you keep reading because your brain wants the pattern to resolve.

The themes that linger are the commodification of art and memory, and the way authoritarian hunger always rebrands itself as “safety” and “procedure.” In this world, corporations show up with lawyer-warrants and militias show up with uniforms, and everyone points guns while insisting they are the adults in the room. The cosmic horror expresses those themes by making information itself feel predatory. The book keeps asking what happens when stories, documents, and evidence aren’t neutral but hungry, when they don’t just describe reality but start rewriting it.

By the time the epilogue hits, the story has basically swallowed its own receipts. You get this security-footage vibe, a kind of “here is the official record” artifact that morphs into something like an art film recap of Sol’s ordeal, complete with a disorienting detour into time weirdness and an attempt to solve the problem from inside the system. It’s a bold move because it refuses the comfort of a clean ending. Instead it gives you the true cosmic horror closer: the feeling that the narrative itself has become contaminated, that even the version of events you’re holding in your hands might be part of the trap.

So, if “True Communication” is possible, is it salvation, or just the final form of invasion? Because sure, maybe you don’t have to be lonely anymore. But also, what if the price is that something else finally gets to speak through you?

In the current King in Yellow tribute ecosystem, this one earns its place by not just name-dropping Carcosa, but by making the concept feel like a modern infection: memetic, bureaucratic, and opportunistically monetized. It reads like a strong “arrival” novel, scaling up the author’s weird-comedy-and-dread instincts into something bigger and meaner without losing the bite.

A well-crafted, distinctive mindfuck that weaponizes archives and loneliness into genuine cosmic dread, and it mostly sticks the landing, even when it’s being a spooky little paperwork pervert.

Read if you want cosmic horror that’s also about paperwork, institutions, and social collapse.

Skip if you want cozy occult puzzles instead of “oh shit, the world is peeling”.

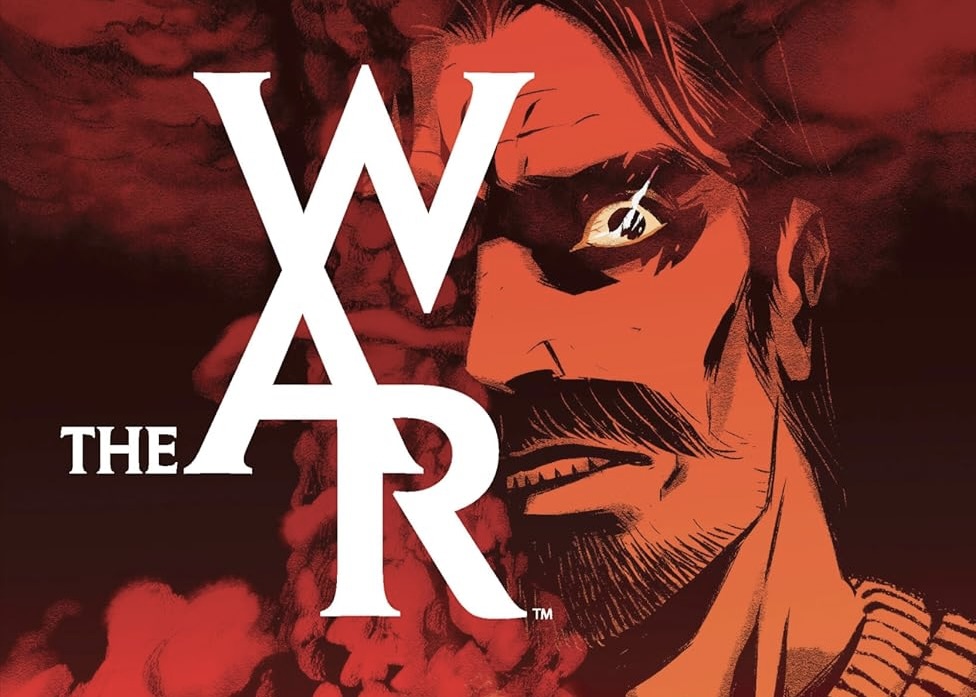

The Truth of Carcosa by Jacob Rollinson,

published January 13, 2026 by Union Square.

Leave a comment