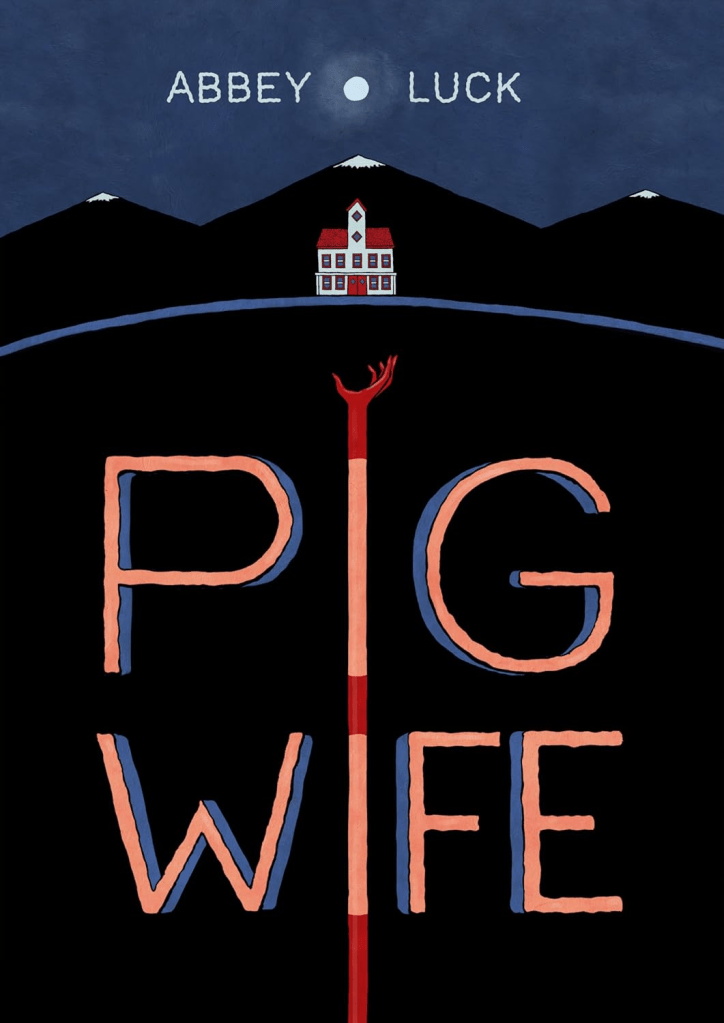

TL;DR: Pig Wife is a claustrophobic, acid-bright bunker nightmare where the real monster is what people do to each other when love gets swapped out for control. It is gross, funny, and weirdly tender in the same breath. It lands more often than it whiffs, even when it gets tonally messy or pokes sore representational nerves.

Abbey Luck comes to Pig Wife from an animation and visual storytelling background, and you can feel that in how the book thinks in images first and exposition second. This reads like a creator who’s used to conveying emotion through pacing, shape, and color, then letting dialogue catch up afterward. Pig Wife is positioned as her first full-length graphic novel, and it plays like a debut that’s not interested in being “nice” or polite. It’s maximal, high-contrast, and willing to get grotesque to make a psychological point. If you’ve followed her broader art and design work, the same instincts show up here: immersive environments, body language that tells on people, and a taste for turning internal panic into external architecture. In other words, this isn’t someone trying horror as a genre exercise. It’s someone using horror as the most efficient tool available to talk about control, shame, and what survives when you’re trapped with people who want to rename you.

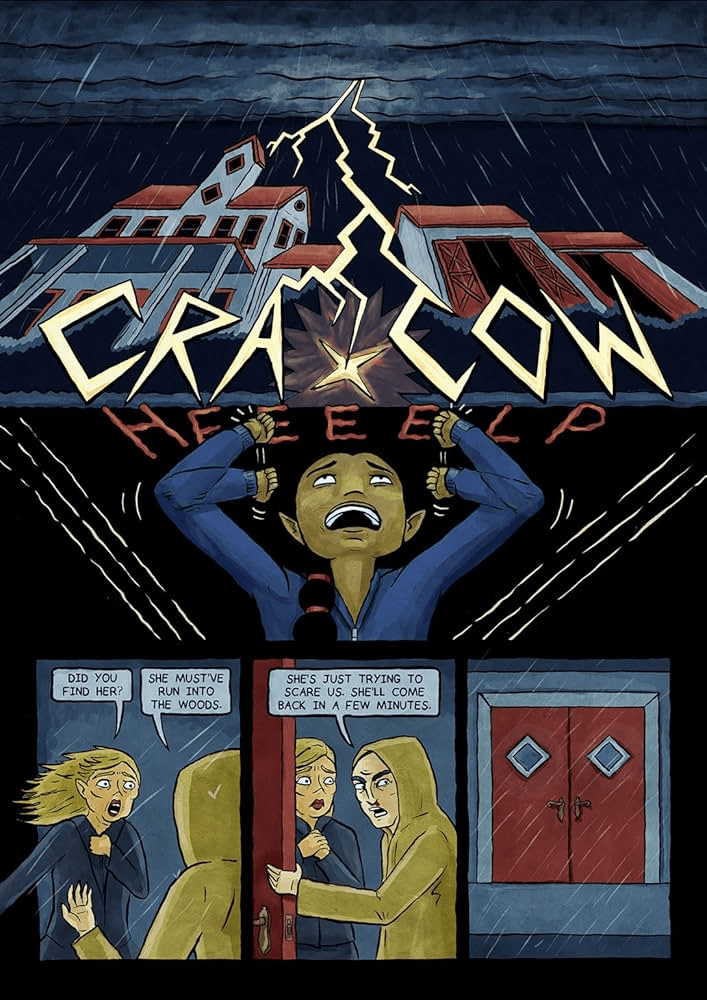

Mary starts the book already loaded like a shaken soda can. Her mom and stepdad drag her to a remote mining town to deal with the estate of dead Aunt Pearl, and Mary’s family dynamic is the usual blended-family misery buffet: resentment, money panic, emotional neglect, and the constant sense that everyone is talking past everyone. After a blowup, Mary bolts, slips into an abandoned mine through a hidden entrance, and immediately learns the horror story rule that should be printed on the back of every teenage skull: running away does not fix your life, it just changes which kind of terrible you are trapped with.

She is sealed underground with two men who have been cut off from the outside world, and they greet her like she is a delivery from God and Mommy and the End Times all at once. The stakes are simple and brutal: get out, stay alive, and do not let their fantasy turn you into furniture. From there the story becomes this relentless tug-of-war between Mary’s will to survive and the way captivity works like a slow infection, rewriting the rules of reality until you catch yourself thinking, Okay, maybe this is just how it is now. That is where the book starts to really bite.

What’s special here is how the comic makes isolation feel like a physical substance. The mine is not just a setting, it is a pressure cooker that forces character into the open. The plot keeps sliding between immediate survival and the slow reveal of how these people were made, and that drip-feed backstory is the real engine. You are not just watching a teen try to escape, you are watching a generational chain of neglect and abuse tighten, link by link, until the present-day plot snaps like a trap.

When the book gets mean, it is not mean in a cheap “look at my edgy horror” way. It is mean like real life is mean: petty humiliations, selfish decisions, and the kind of parental damage that leaves a kid furious at the wrong target because the truth is too big to hold. The family stuff is not window dressing. It is the psychological kindling that makes Mary vulnerable to the bunker’s warped little universe. The horror is not just “bad men in a hole.” It is the whole messy apparatus of control that Mary has been swimming in aboveground too, now stripped down to its most obvious, disgusting form.

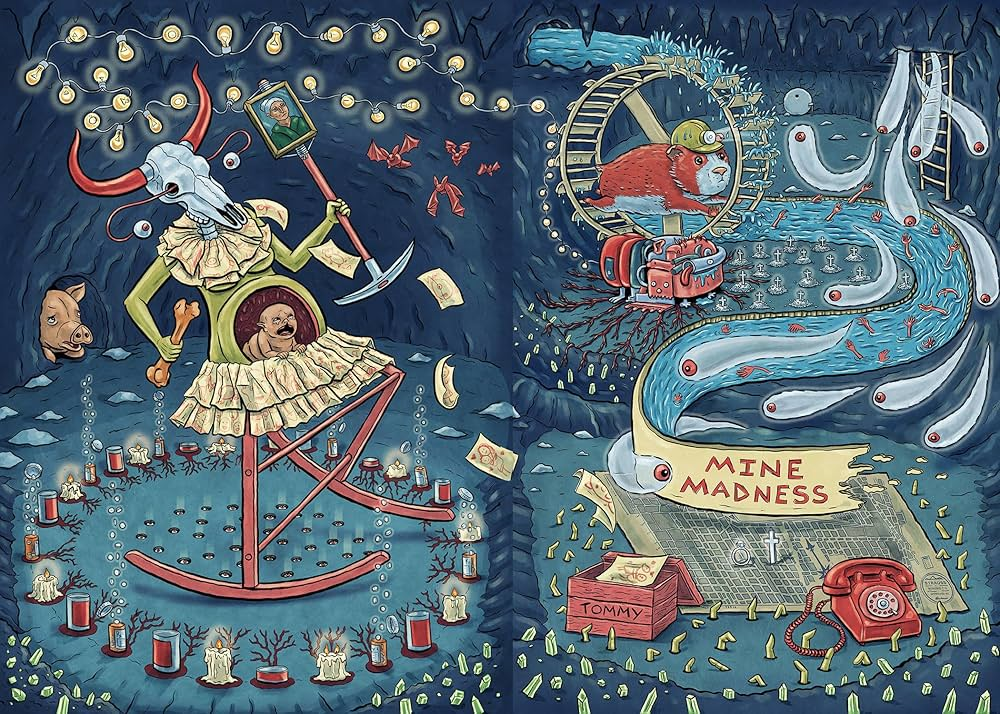

The best moments are when the book leans into visual metaphor and nightmare logic instead of playing everything straight. It is at its strongest when it lets the art carry emotional information that dialogue never could. When Mary spirals, the page language spirals with her. When the bunker reality becomes unbearable, the comic slips its leash and turns into a fever map. Those surreal interludes and psychedelic breaks are where this feels like a real “indie swing” instead of a competent genre product.

The aesthetic is intentionally ugly-cute in a way that will be polarizing: chunky expressions, grotesque bodies, and a cartoon sensibility that makes the violence feel both more absurd and more upsetting. That clash is either the secret sauce or the reason you bounce off. I loved it, because it keeps the book from becoming a prestige misery-drama where everyone whispers trauma in tasteful lighting. This looks like someone drew it with their teeth clenched. The nastiness is part of the honesty. Also, the book’s comedic timing is sharp enough to be dangerous. Sometimes the jokes land like a pressure valve hissing open, and you laugh and then feel like an asshole because the scene is still horrible. That’s the sweet spot for this kind of horror.

Now the flip side, because I am not handing out charity points. The tone can wobble. When the comic leans into dark humor, it can either intensify the dread or undercut it, and a couple stretches flirt with “I wandered into a different comic for ten minutes” energy. It is a tricky balancing act. Most of the time it works because the underlying situation is so bleak that humor feels like the only sane reaction. But a few beats come off a little too “bit” when the story needs to be fully locked in on dread.

There is also the question of portrayal. The comic is clearly angry at abuse and sympathetic toward its victims, but it sometimes brushes up against horror shorthand around mental illness and disability-coded grotesquerie. I do not think the intention is cruel, but intention does not magically solve impact. It is worth naming because it is part of what might make this feel thorny to some readers. If you have zero patience for that kind of trope-adjacent imagery, this might be a hard no.

This is a story about dehumanization and the lies people tell themselves to justify it, especially the “I’m protecting you” lie that is actually “I’m protecting me.” The horror machinery expresses that theme through confinement and bodily degradation: people reduced to roles (wife, son, burden, sinner), then reduced further to needs (food, sex, obedience), until identity is something you have to fight to keep. How much love can you offer someone who has only ever learned love as ownership?

In the current wave of horror comics that blend trauma, absurdity, and body disgust, Pig Wife sits closer to “swing big, risk the mess” than “polished, safe, bookstore-friendly.” It is not trying to be pretty. It is trying to be sticky. For a debut graphic novel, that ambition is the point, and even its misfires feel like the cost of making something personal instead of product. A nasty, heartfelt, claustrophobic fever-dream that earns its weirdness, even when the tone wobbles and a few choices land like a bruise you keep pressing to see if it still hurts.

Read if you like bunker horror where the “monster” is a whole family system rotting in the dark and you crave surreal, psychedelic visual breaks that translate emotion into nightmare scenery.

Skip if you need clean tonal consistency and hate comedy showing up at the worst possible time.

Pig Wife by Abbey Luck,

published January 13, 2026 by Top Shelf.

Leave a comment