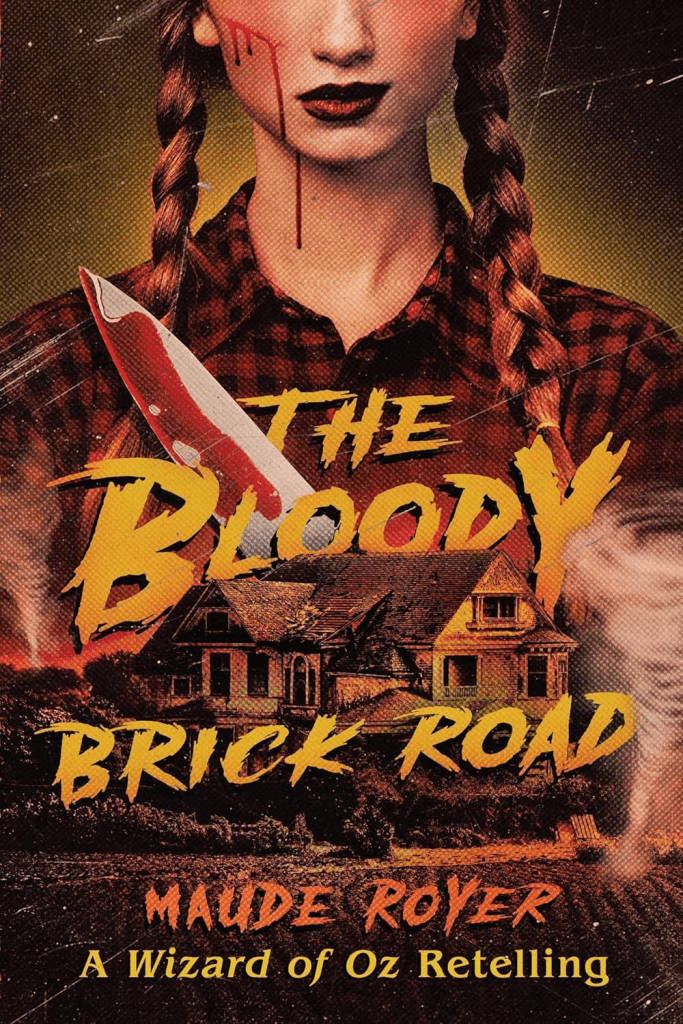

TL;DR: This is a mean, pulpy Wizard of Oz remix that smashes fairy-tale iconography into Quebec-set serial-killer filth, with shoe obsession, extremist weirdos, and enough gore to make your lunch file a complaint. It’s fun as hell when it’s sprinting and disgusting, but it also overreaches, wobbles tonally, and doesn’t always land the emotional swings it keeps daring you to feel.

Maude Royer’s background helps explain the vibe: she came up writing fantasy (and kids’ work) before pivoting into adult horror, and you can feel that “story-first, momentum-first” engine in the way this book keeps clicking into the next set piece. The English edition is a 2026 translation, originally published in Canada in 2022. That matters because the book reads like it wants to be devoured in big bites: cliffhangers, rotating viewpoints, sharp turns into nastiness, then a pivot into a procedural beat, then right back to “what the fuck did I just read.”

In Montreal, Dorothy Noroît is a woman whose life has been hollowed out by an old catastrophe, and she’s wired her remaining sanity to two things: motherhood as an ache she cannot quit, and shoes as a private religion. Around her, a cast of modern-day Oz “companions” orbit the same gravitational sinkhole: a heartless con-artist type, a fearful shut-in, and a gentle, easily used farm kid. When a string of murders starts stacking bodies, detectives Henri Duhaime and Emilianne Saint-Gelais begin to see a pattern that leads back to a single, cursed slice of time in 1994 and a cohort of NICU babies who shared the same hospital window. Meanwhile, Dorothy’s path tangles with a charismatic activist, Antoine Lebeau, who fronts a group called the Winged Monkeys and talks about human worth with the dead-eyed confidence of a cult leader who thinks he’s doing society a favor. The stakes aren’t “get home to Kansas,” they’re “survive a world where bodies become arguments, and arguments become knives.”

Royer doesn’t just modernize the Oz archetypes, she weaponizes them. The “lion” figure isn’t simply timid; the fear curdles into isolation and dependence. The “tin man” energy isn’t quaint; it’s predation and entitlement. The “scarecrow” sweetness becomes a vulnerability the world keeps exploiting until something snaps. And the book’s grossest joke is that the slippers aren’t a symbol of wonder, they’re an evidence problem, a fetish object, a ritual tool, and a breadcrumb trail. The procedural reveals are often delivered with a nasty little grin, like: oh, you thought this was whimsical? Here’s a jar.

The book is brisk, direct, and scene-forward. The prose isn’t trying to be lyrical, it’s trying to be effective: quick sensory cues, a hard pivot into dialogue, a button at the end of a chapter that pushes you into the next one. When it works, it’s addicting. The Dorothy shoe-boutique bits, for example, capture obsession in a way that’s both funny and sad: she’s not buying footwear, she’s buying a controlled hit of meaning. The detectives’ banter also helps cut the heaviness so it doesn’t become an unbroken sludge of misery. But the downside is that the emotional beats can feel “told” rather than fully metabolized. Some characters read more like functions in the Oz machine than like people who breathe off-page, and a few escalations feel like the book going, “What if we made it even more fucked up?” instead of “What would this specific person do next?”

Under the splatter and the punchlines, this is a book about dehumanization, especially around reproduction, disability, and who society decides is “worth” the cost. Lebeau’s rhetoric about premature babies is presented as seductive and monstrous at the same time, which is exactly how extremists actually work. And Dorothy’s origin wound is pure body-horror grief: the collision of fate, medicine, and a personal loss that turns into an obsession that never stops chewing. The book sews green-glass dread and a sort of queasy question: how many stories do we tell ourselves about “mercy” before it becomes permission to do violence?

As adult horror fairy-tale remixes go, this sits closer to pulpy grindhouse and tabloid-mystery than prestige dark fantasy, and that’s both its charm and its ceiling. It’s a sticky, bingeable mess that absolutely has its own greasy voice, even if it doesn’t fully earn every big swing.

A nasty, high-concept Oz splatter-procedural that’s frequently entertaining as shit, occasionally smart, and a little too uneven to be truly great.

Read if you want Oz iconography dragged through a crime-scene gutter, lovingly.

Skip if you want “retelling” to mean cozy homage, not a boot to the teeth.

The Bloody Brick Road by Maude Royer,

published January 6, 2026 by Gallery Books.

Leave a comment