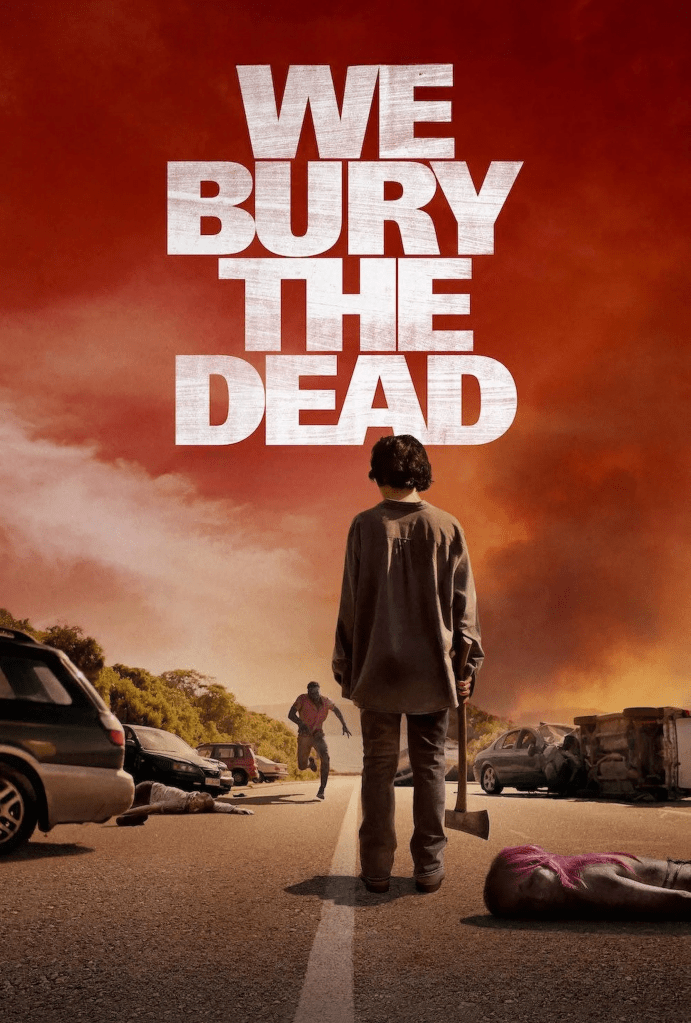

TL;DR: A grief-soaked, zombie-adjacent road movie where the real monster is unfinished business. Daisy Ridley drags you through a localized apocalypse in Tasmania, chasing closure with bloody hands and a tight jaw. It’s not a splatter buffet, it’s a sad, sharp gut-punch with one genuinely nasty audio choice. Solid.

Zak Hilditch writes and directs this thing, and if you’ve seen These Final Hours, 1922, or Netflix’s Rattlesnake, you know his lane: ordinary people making desperate choices while the world quietly, politely ends around them. We Bury the Dead feels like him trying to smuggle an intimate relationship autopsy into a zombie movie’s luggage, then acting innocent when the baggage starts screaming at baggage claim. It also reads like a deliberate pivot away from “global pandemic, save the world,” toward “one place is on fire, everyone else is checking the morning news and eating cereal.”

Ava Newman (Daisy Ridley) heads to Tasmania after a catastrophic military screw-up wipes out roughly 500,000 people. Her husband Mitch (Matt Whelan) was there on a work retreat, and Ava signs onto a body retrieval unit because “he’s definitely dead” is not the same as seeing it. The military quarantines zones, corpses sometimes “come back online,” and Ava teams up with Clay (Brenton Thwaites), a charming dirtbag with a vibe like “I cope by making jokes and pretending I’m fine.” They push into restricted territory, run into a soldier named Riley (Mark Coles Smith), and the trip turns into a moving target of hope, dread, and the ugly logistics of mass death.

The scale and the attitude of the film are its strongest assets. This isn’t “the whole planet is rubble.” It’s “Tasmania is an open wound,” and the movie stays locked on one woman’s need to put a period at the end of a sentence that got cut off mid-word. The body-retrieval framing is a nasty little masterstroke because it forces the horror into routine: lifting, tagging, hauling, trying to be respectful while your stomach is doing backflips. And the zombies, when they show up, are not immediately your standard sprinting rage machines. They are often docile at first, more “wrong” than “attack,” which makes the whole thing feel like grief made physical.

Then there’s the teeth. Dear God, the teeth. Hilditch gives the undead a grinding habit, and the sound design is so viscerally awful it feels like the movie is flossing your brain with barbed wire. It’s a brilliant choice and I hated it, which is kind of the point. That noise alone does more work than a dozen cheap jump scares.

The film is patient to a fault, but it’s also often gorgeous in that scorched, end-of-the-road way. The Tasmania travel stretch leans into wide, smoldering landscapes and slow, ominous movement, with Ava and Clay cutting through spaces that look abandoned five minutes after God left the chat. The movie also isn’t afraid to spike its misery with moments of life, including pop and rock needle-drops against bleak imagery, plus pockets of gallows humor from Clay and the crew. That tonal cocktail mostly works: it keeps the film from becoming a prestige-dirge while still letting the sadness breathe.

Where it wobbles is the midsection, when the movie drifts toward the genre’s oldest chorus: “the dead are scary, but the living are worse.” It’s not that those beats can’t work. It’s that the film has already built a better engine, one powered by mourning and bureaucracy and the sheer exhausting labor of aftermath, and then it briefly swaps in a more familiar zombie-thriller gearbox. Add in marriage flashbacks that sometimes feel like they’re teasing a reveal for slightly too long, and you can feel the momentum get a little sketchy.

Still, Ridley carries the center with a performance that’s mostly quiet, clenched, and human. She sells Ava as someone who doesn’t want heroism, she wants confirmation. Thwaites is a solid counterweight, warm enough to be believable, slippery enough to keep you wary. And when the film returns to its more contemplative posture in the back third, it remembers what it’s actually about: closure as a wound you choose to reopen because the alternative is living with a question mark stapled to your chest.

Grief is the obvious theme, but also the cruelty of “maybe.” The zombies aren’t just monsters here, they’re unresolved endings shambling around, forcing you to ask whether seeing a husk is kinder than seeing nothing. The movie’s lingering mood is ash-in-the-mouth uncertainty. Not “what would I do in a zombie apocalypse,” but “what would I do if the person I loved became a question I could never answer.”

Ultimately, this feels like Hilditch doubling down on his specialty, intimate character suffering under apocalyptic pressure, but swapping the ticking-clock panic of These Final Hours for something more procedural and mournful. In the landscape of zombie flicks, it’s a “zombie movie that sometimes refuses to be a zombie movie,” and that’s both its freshest trait and its biggest gamble.

A bleak, often beautiful grief-machine with one unforgettable audio nightmare, even if it occasionally trips on the same old “humans are the real monsters” shit.

Watch if you’re into grief-horror, slow dread, and emotional splinters.

Skip if you require constant action, big set pieces, or a rising-infection escalation.

Directed by Zak Hilditch, written by Zak Hilditch.

Released January 2, 2026 by Vertical.

Leave a comment