TL;DR: Campbell’s debut novel turns Liverpool into a haunted conscience, skewers true-crime voyeurism, and builds dread like mold in your ribs. Precise prose, pitiless psychology, and an ending that feels inevitable and rotten. Fifty years on, it still bites and then asks why you wanted to watch.

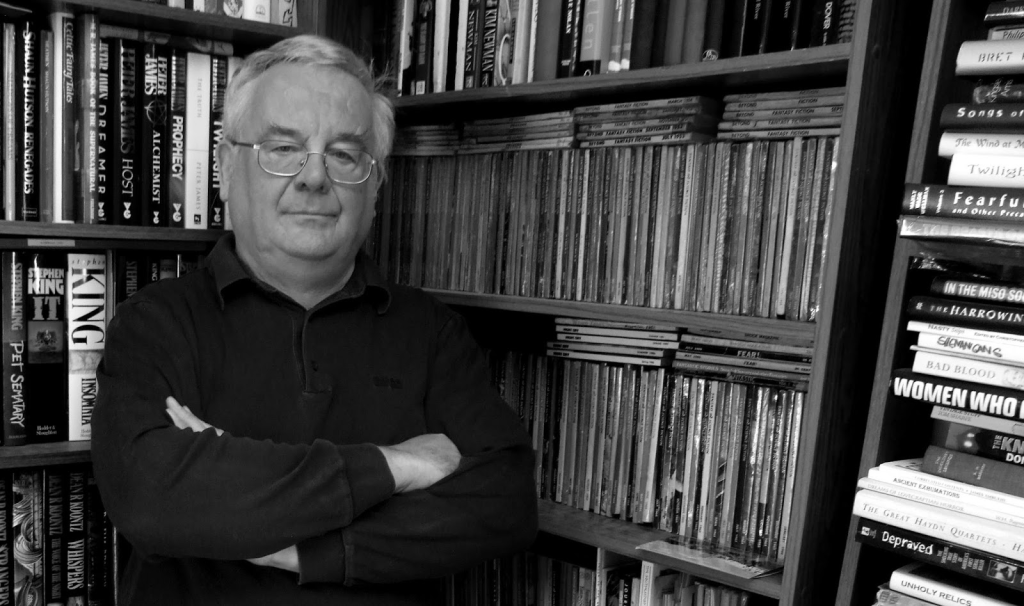

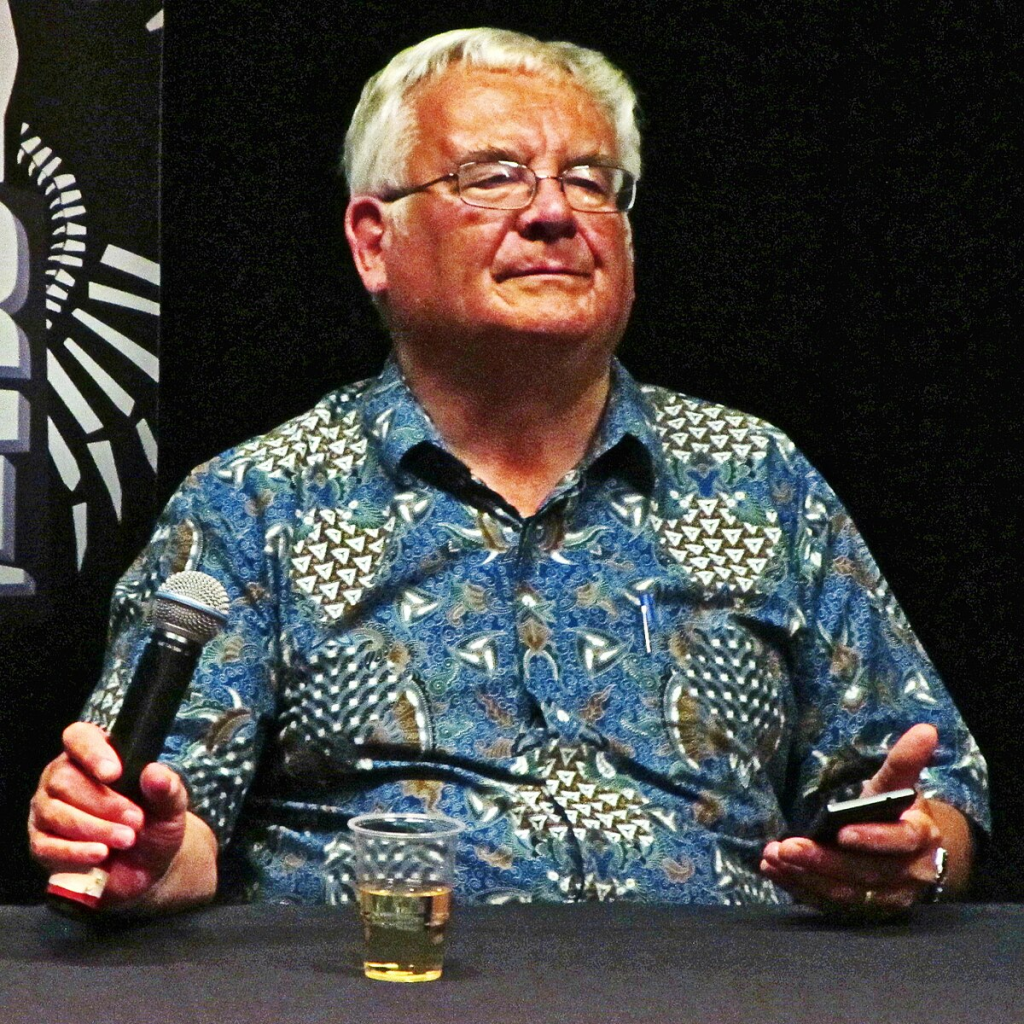

Ramsey Campbell is Britain’s quiet assassin of horror. He started as a teenage acolyte riffing on Lovecraft, then slashed free and made Liverpool his haunted organ. By 1976 he’d already proven himself a short-story killer with collections like Demons by Daylight, swapping cosmic tentacles for urban mildew, bad lighting, and human guilt thick enough to spread on toast. The Doll Who Ate His Mother was his first published novel, a grimy, street-level murder trek that points toward later masterworks where psychology does more damage than any monster: The Face That Must Die, Incarnate, The Influence, the whole “let me show you how ordinary life curdles” catalog. Campbell’s lane is atmospheric dread married to moral rot. He writes cities like they’re alive and quietly judging you, and he writes people like they’re sleepwalking off cliffs with smiles on.

In The Doll Who Ate His Mother a young schoolteacher, Clare Frayn, survives a horrifying car accident in nocturnal Liverpool. Her brother does not. Worse, someone steals the evidence in the ugliest way possible. A slick true-crime writer, Edmund Hall, swoops in with a book deal and a theory about an old schoolmate turned predator. Reluctantly, Clare joins a grim amateur manhunt through back streets, derelict houses, and crumbling psyches. The hunter’s trail runs through a local history of spiritual grifters and homemade rituals, and the closer they get, the more Liverpool itself feels complicit. The novel isn’t a whodunit so much as a what-are-we-really-made-of. Think serial predation, occult leftovers, and the human urge to stare at car wrecks because some part of us wants to see the worst. The finale delivers a mud-slicked reckoning that’s as much about childhood nightmares as it is about bones in the ground.

This book is a pressure cooker. Themes: guilt, voyeurism, exploitation, class friction, the way family “love” can deform into a cage, and how the present is just the past wearing fresh skin. There is literal hunger in here, sure, but the real appetite is psychic. People feed on each other. Some take attention. Some take safety. One vile little soul takes more.

Symbolism shows up in small, nasty packages. Dolls crop up as creepy mirrors. They hold power, secrets, and an obscenity of birth that Campbell wields like a scalpel. Basements, lamps, sodium-orange night, and wet earth turn Liverpool into a half-awake beast. You can practically smell the damp. The city is the novel’s big symbolic organism. It shelters ghosts of demagogues and hustlers, and it leans in like a nosy neighbor while the characters try to keep their masks straight.

Campbell’s style is precise, patient, and mean. He doesn’t shout. He whispers the worst thing into your ear right when you realize you’re alone. Sentences carry dread like static electricity. He loves the tiny sensory detail that opens a trapdoor. He is not here to spoon-feed gore. He is here to watch you watch, then make you feel weird about wanting to.

Fifty years on, the book reads like an early indictment of content culture. Edmund Hall is proto-content. He packages other people’s pain and calls it “research.” He’s suave, hollow, and magnetic in the way only an opportunist can be. Campbell doesn’t sermonize. He sets Edmund next to Clare’s ordinary decency and lets the comparison corrode you. The question becomes: which is worse, the demon or the documentary? Who does more damage, the eater or the exploiter who sells the recipe?

Clare is the soul of the thing. Guilt chews her, shame handcuffs her, but she keeps moving. In a lesser novel she would be the Final Girl, stabbed and purified. Campbell gives her something smarter. She has to face the truth about the killer, the city, and her own complicity in chasing the spectacle. The book’s lingering aftertaste is not fear of the boogeyman. It’s fear of our appetite for him.

The occult thread matters less as literal magic and more as a metaphor for inherited monstrosity. The past leaves artifacts that demand attention. You dig in the wrong garden and up comes the family business. Birth itself becomes an image of entrapment. Creation can be corrupt. Nurture can be a form of predation in a polite dress.

In 1976 this was a nasty piece of originality. Campbell drags the horror novel out of creaky mansions and into municipal orange glow. He braids serial predation with a scuzzy folk-occult residue and lets the two feed each other. Half a century later we’ve overdosed on serial-killer fiction, but Doll still feels singular because Campbell keeps the camera pointed at shame, class, and complicity rather than giddy body counts.

Measured and deliberate, the book breathes like a stalker. If you need jump scares every five pages, go watch a streaming show that thinks “loud violin” equals terror. Campbell wants you stewing in moral humidity. He slow-rolls dread until the basement scenes hit like a punch you saw coming and could not dodge. When the plot goes subterranean, the tempo kicks just enough to make your stomach drop.

Clare is quietly excellent. She is capable, blinkered, and painfully human, and the book never treats her as a prop. Edmund is a beautifully awful portrait of a man who believes “I’m telling the truth” is the same thing as “I’m doing good.” The villain is not a mustache twirler. He is a product of household damage, social neglect, and something rotten that wants to repeat itself. Even side characters feel observed rather than placed. Campbell never forgets that horror is a social genre. People make monsters, then pretend the monster arrived by courier.

This is thick with atmosphere. The scares are cumulative rather than spiky. There are sequences in basements and derelict rooms that had me curling my toes like a cat about to bolt. The city’s sodium haze is its own jump scare. And yes, there are images here that will just sit in your head humming, like a fridge that might contain something you do not want to open. I would not call it splatterpunk. It is worse. It is patience.

Lean and quietly lethal. Campbell’s sentences walk you right up to the thing and then make you admit you wanted to see it. He does not grandstand. He just keeps choosing the detail that knifes you. There is humor, but it is the bitter, human kind, not wink-wink camp. If you’ve got a grudge against mediocre writing, you will feel seen.

The Doll Who Ate His Mother still slaps. It is bold in its restraint, original in its urban moral lens, and gutsy enough to make true crime itself the secondary monster. It is not perfect for every reader in 2025, but that is mostly because it refuses the sugar rush. Good. Let the weak have their candy.

Recommended for: Readers who like their horror damp, morally ugly, and weirdly tender. Fans of decayed cities, doomed basements, and dolls with terrible ideas. Anyone who has ever side-eyed a slick true-crime bro and thought, “you would absolutely monetize my funeral.”

Not recommended for: Folks who need car chases every chapter. People who think dolls are adorable keepsakes and would like to keep thinking that. Anyone who believes the past is safely buried and that basements are for storage rather than spiritual biohazards.

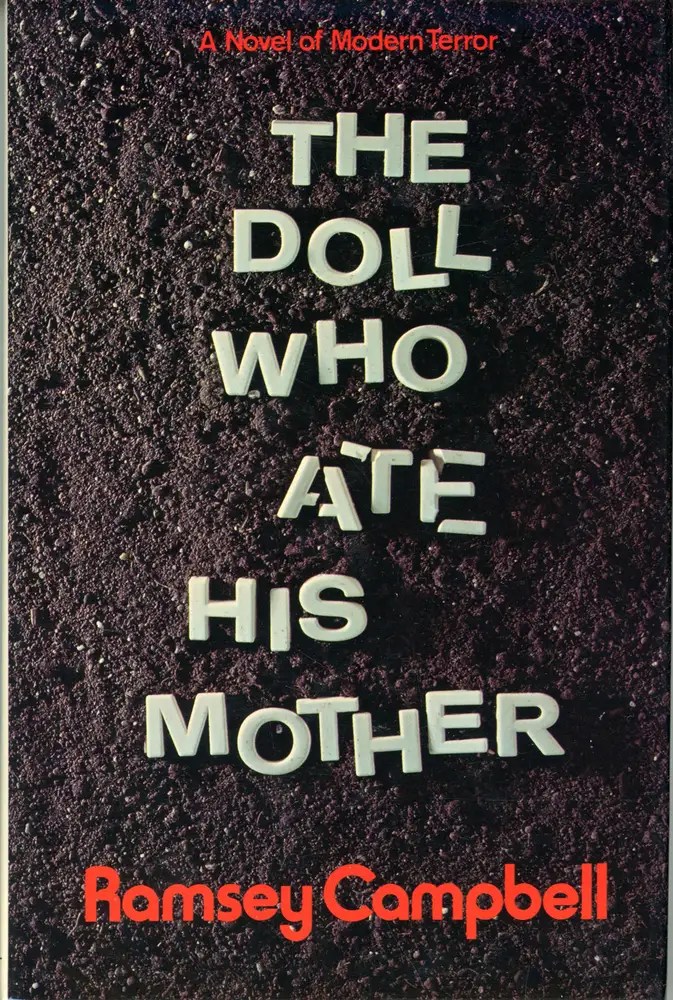

The Doll Who Ate His Mother by Ramsey Campbell,

published 1976 by Bobbs-Merrill Company.

Leave a comment