TL;DR: A boys’ water polo camp becomes a chlorinated horror factory where cruelty spreads faster than any rash, and the scariest monster is a kid with status. Polinger turns middle-school social physics into dread cinema with brutal performances and a deranged, choir-haunted score. It lands hard if you can stomach the cringe-pain.

Ben is twelve, newly transplanted, and walking into that very specific kid-hell where everyone already has a pecking order, a slang dialect, and a list of who is “safe” to be seen with. At the Tom Lerner Water Polo Camp in the summer of 2003, he clocks the alpha pack fast. Jake (Kayo Martin) runs the place with a grin that says he’s joking, while his eyes say he’s taking notes on how to ruin your fucking life. Ben (Everett Blunck) wants what every kid wants in that moment: a seat at the table, a nickname that doesn’t stick to him like gum, and proof he’s not the next sacrifice.

The sacrificial lamb is Eli (Kenny Rasmussen), an oddball with a visible skin condition and the social positioning of a kicked lunch tray. Jake declares Eli has “the plague,” a made-up contagion with made-up rules that everyone treats like scripture: don’t touch him, don’t stand too close, wash up if you brush past him, and for the love of God don’t be seen enjoying his company. The stakes are brutally simple and totally adolescent: belong, or get erased. Coach “Daddy Wags” (Joel Edgerton), the lone adult presence, tries to keep the boys pointed vaguely toward sportsmanship, but he’s basically a lifeguard at a pool full of piranhas.

What’s great about this film is how Charlie Polinger takes a premise that could have been a neat little bullying drama and instead makes it feel like a curse movie where the curse is attention. The “plague” is a social technology. Jake uses it the way adults use money or titles: to control proximity, to enforce loyalty, to make fear look like common sense. And the film understands the worst part: the game works because it’s fun. It’s fun to be included. It’s fun to have a target that isn’t you. It’s fun to watch someone else squirm and tell yourself you had no choice.

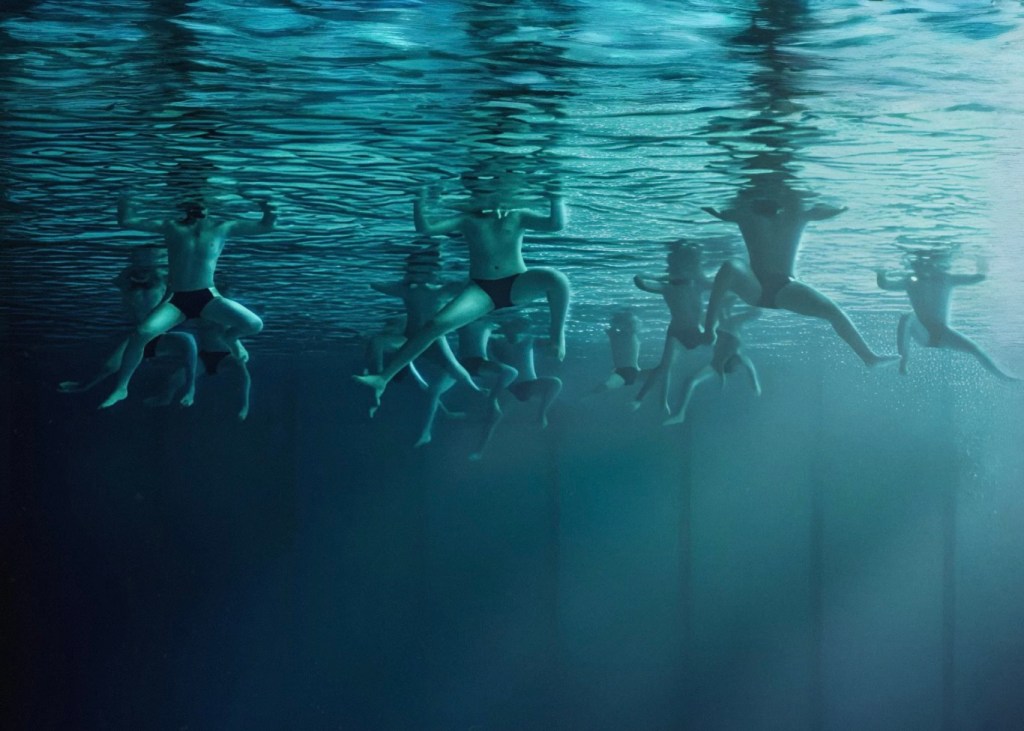

Polinger’s debut is drenched in bodily humiliation, the kind that makes you want to crawl out of your seat and shower with steel wool. Puberty is treated like a haunted house attraction: rashes, pimples, sweat, wet hair, locker-room air, and the constant sense that your own body is betraying you on camera. The film weaponizes the pool itself, that big blue rectangle of “health,” into something alien and predatory. Underwater shots turn the boys into floating torsos and kicking legs, like a school of half-formed creatures learning how to hunt. It’s gorgeous and unsettling, and it keeps reminding you that this is an ecosystem, not a summer camp.

Polinger shoots this like a fairy tale for people who still have nightmares about seventh grade. The pacing is tight, but it has the confidence to sit in silence and let shame bloom. When it goes loud, it goes biblical: Johan Lenox’s score leans into voices, breath, chant, and ritualistic pounding that turns ordinary competition into something tribal and feral. The sound design keeps you trapped inside Ben’s head, where every glance is a threat assessment and every laugh might be about you. The cinematography, often cool and clinical, makes the camp feel sterile in the way hospitals are sterile, which is funny because the real disease here is social.

Everett Blunck carries the film with a face that can hold empathy and terror at the same time. You can watch him do the math in real time: what he believes is right versus what will keep him alive in the hierarchy. Kayo Martin’s Jake is one of those truly infuriating kid villains, not a cartoon psycho, just a smart, charismatic little shit who understands leverage. Rasmussen’s Eli is the quiet miracle. He is not written as a saint or an inspirational prop. He’s strange, funny, stubborn, occasionally maddening, and unmistakably human, which makes the cruelty aimed at him feel even more rancid.

This is a movie about contamination, but not the medical kind. It’s about how shame spreads by touchless contact. It’s about how boys are trained, early, to confuse dominance with safety, and how “being normal” becomes a form of self-harm. The horror expresses that through the body because that is where kids feel everything first. When the social pressure spikes, skin reacts, breath shortens, posture collapses. The next day, what stuck in my ribs was the question the film keeps whispering: how much of your adult self is just the version of you that survived the camp?

Polinger, who wrote and directed the film, is making his feature debut here, and it feels like a filmmaker with a specific wound and a sharp set of tools. Interviews around the release have framed the project as deeply personal and rooted in his memories of boyhood social dynamics, with details pulled from that era’s texture and rituals. That context matters because the movie doesn’t feel like an “issue film.” It feels like an exorcism with excellent lighting.

The Plague earns a spot near the nastier, weirder end, not because it invents bullying, but because it shoots it like a contagion ritual and refuses to soften the corners. It’s not genre-defining, but it’s a hell of a calling card and a reminder that the most terrifying haunted house is a locker room with no adults who matter.

A vicious, beautifully crafted little nightmare that understands the real plague is wanting to be loved by the people who are hurting you.

Watch if you crave coming-of-age horror that treats social rules like life-or-death folklore.

Skip if you want straightforward scares instead of psychological suffocation.

Directed by Charlie Polinger, written by Charlie Polinger.

Released January 2, 2026 by IFC Films.

Leave a comment