TL;DR: This is end of the world as compost, not spectacle. Forests, kudzu, horses and bees all want a piece of your soft human meat and your bad history. It is weird, ambitious and sticky as hell, the kind of book that makes you feel small, guilty and absolutely thrilled you picked it up.

Corey Farrenkopf has been quietly building a reputation as an eco-weird guy with Haunted Ecologies and a stack of magazine credits; The Final Sight feels like him turning the dial to apotheosis. Tiffany Morris brings her L’nu’skw Mi’kmaw eco-horror chops from Green Fuse Burning and Elegies of Rotting Stars and just lets loose here. Eric Raglin, who runs Cursed Morsels and already proved he can juggle politics and viscera in Antifa Splatterpunk, anchors the back half with a grounded, socially loaded weird novella.

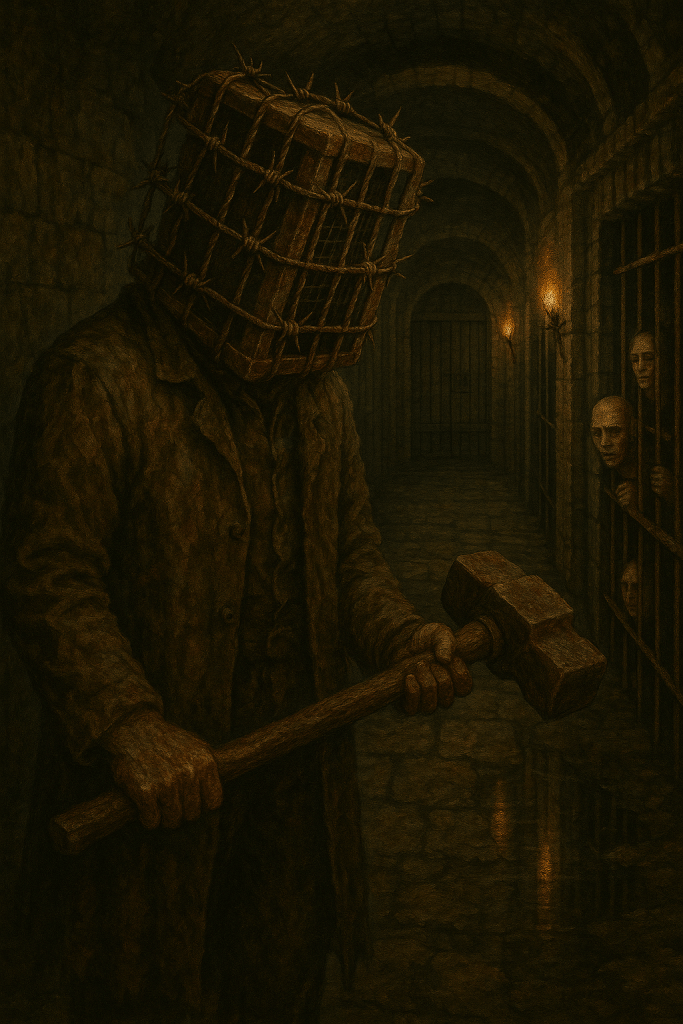

Across the collection, the world has basically decided it is done with us. In The Final Sight, a small, dying community perched over a chasm full of fused animal–human “amalgams” debates whether to stay in their rotting town or cross through that living pit toward an impossibly lush forest. In Morris’s suite of stories, lovers, kids and workers navigate kudzu-choked cities, kelpie horse hauntings and hive-minds of bees and ghosts that may offer transcendence or just a prettier way to die. Raglin’s On Phantom Wings follows estranged friends on a birding trip where impossible birds and real-world bigotry collide and things with wings start to feel like both salvation and doom. Everyone is trying to cross something, everyone is food for something else.

I love how the book deeply commits to “verdant” as both beauty and threat. Farrenkopf’s chasm full of stitched-together beasts feels like a long, slow panic attack. Limbs and beaks and hooves weld together from industrial runoff and bad decisions; it is grotesque, but the real horror is how banal it feels, like this is simply where capitalism and climate collapse were always heading. Morris takes that same impulse and turns it up until it is neon. Her kudzu city in The Neon Dread of Leaves is one of those settings that instantly lives in your head: gasping vines, golden spores, two exhausted wives trudging through a world that smells like sweetness curdled into rot. Kelpie transformations, death-courting flower men, bee cults that might actually love you back, all hit that sweet spot where folklore, grief and body horror snuggle up together. Raglin closes the set by making the monsters share the stage with police brutality, transphobia and burnout. The phantom birds are cool as hell, but the real punch is how he shows systemic violence as another kind of predatory ecosystem.

Nobody here phones it in. Farrenkopf writes in a rotating close third that feels like an oral history of the end; his sentences are long, sandy, a little choked, like everyone is out of breath and still trying to explain. The Final Sight moves between leader, farmer, child and dying Watcher, and the structure lets the chasm feel communal rather than just set-dressing. Morris’s prose is lush and sticky; she leans into scent and texture so hard that you practically feel pollen in your lungs and salt spray on your face. Her stories are shorter and more dreamlike, but they never dissolve into pure vibe, there is always a beating emotional heart under the moss. Raglin’s style is more direct and nervous, full of social awkwardness, road-trip pacing and then these sharp eruptions of uncanny shit that feel like a panic spike on an EKG. Together, the three voices feel distinct yet weirdly braided, like different roots feeding one ravenous tree.

Eco-dread is the big undercurrent, obviously, but it is not the lazy “humans bad, trees good” thing. The book keeps worrying at complicity, at how much of the apocalypse we carry in our bodies, our faiths, our families. The cannibal religions and Watchers in Farrenkopf read like a roast of reactionary nostalgia; they would rather stare at a forest they will never touch than risk changing anything. Morris keeps coming back to hunger and seduction: horses from the sea, bees that know your secrets, ghosts selling bouquets that double as exit doors. The horror machinery is always tied to longing, to grief and to colonization of land and body. Raglin, meanwhile, threads in how marginalized people live in a constant state of haunting even before any spectral wings show up. It’s all a thick mix of honey, blood and fertilizer, and the nagging question of whether joining the writhing ecosystem might actually be less monstrous than what we are doing now.

In the the larger context of eco-horror, this sits comfortably amongst the best, but the Indigenous perspective from Morris and the explicitly anti-fascist pedigree of Raglin’s other work give it a particular bite. Farrenkopf’s Haunted Ecologies felt like a thesis; The Writhing, Verdant End feels like the next-level group project where the thesis sprouts limbs and claws and drags three writers and a small press into something bigger.

This is excellent, weird and memorable eco-horror from front to back, the kind of fucked-up, leafy nightmare that will have you eyeing your houseplants and your own shitty species with the exact same mix of awe and fear.

Read if you crave fucked-up eco-apocalypse that feels intimate rather than panoramic spectacle.

Skip if you need your end of the world stories clean, hopeful and low on gore or systemic ugliness.

The Writhing, Verdant End, published December 9, 2025 by Cursed Morsels.

Leave a comment