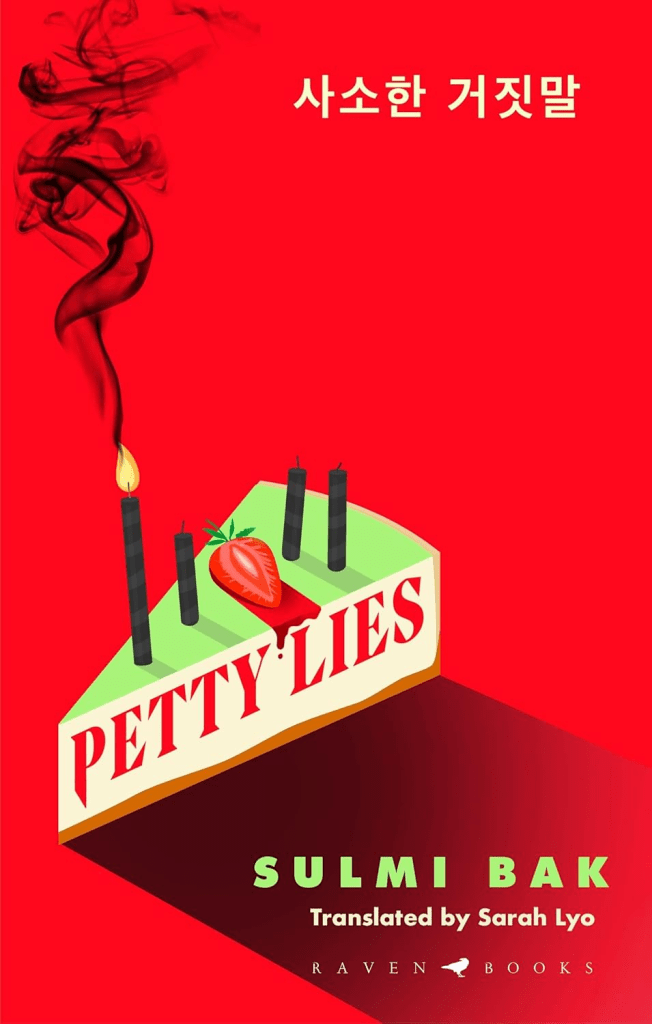

TL;DR: Petty Lies is a vicious little psychological crime novel about revenge, animal cruelty, and rich people hiding their rotten kids behind money and bullshit. It is smart, nasty, and grounded in real world horrors, even if it lectures a bit, and it will absolutely fuck up your next quiet family dinner.

Sulmi Bak is a former journalism major, and you can feel that reporter brain ticking away in the background. Petty Lies is her debut, followed by The Silence of the Swan and Dalwhinnie Hotel, which sets this up as her opening shot in a career clearly interested in crime, class, and human ugliness. It reads like the work of someone who has been stockpiling horrible stories from the news and finally decided to weaponize them into fiction.

The book is built as four interlocking letters: from Mira, a private tutor with a catastrophic family history; from Moon Jiwon, the high status mother who hired her; from a son whose inner landscape is deeply wrong; and finally from a voice that signs off with a kind of exhausted, scorched earth calm. The spine of the plot is simple in the best way. Years ago, a brutal act of animal cruelty and a mother’s unhinged defense of her prodigy son contributed to another woman’s suicide and the death of her disabled child. Mira has lived with that fallout and sees her chance when she finds a way into the culprit’s house as a tutor. What starts as a revenge fantasy soon runs into something worse than the golden boy she thought she was hunting: the younger brother, Yujae, whose casual confession about killing neighborhood dogs is one of the book’s coldest, most fucked up scenes. Mira’s “solution” is a poisoned birthday cake and a long, vicious letter explaining exactly why. From there, Jiwon and later the son write back, each letter twisting the knife and complicating who, if anyone, actually deserves sympathy.

What makes Petty Lies special is how mundane the horror feels. This isn’t a haunted house; it is a haunted neighborhood, a haunted set of court cases, a haunted chain of shitty decisions. Bak keeps returning to marginal victims, especially animals, and to how cheaply the law prices their suffering, reciting real world cruelty cases like a prosecutorial litany. It sounds almost clinical, which somehow makes it feel even more like a punch in the throat. The book is at its best when it lets that anger bleed into the monologues: Mira’s bitter fixation on Bell the dachshund and the Somang and Eunbi cases, or Jiwon’s raw admission that she absolutely did play favorites between her sons. That mix of true crime detail, maternal guilt, and teenage sociopathy gives everything a sweaty, “this could be on the news tomorrow” vibe that sticks.

Stylistically, this thing is a long, angry argument written in beautifully controlled prose. Each section is one sustained voice, heavy on rhetorical questions, little asides to “you,” and that specific Korean domestic-drama rhythm that slides from polite into poisonous in a heartbeat. Even in translation, the sentences feel sharp and deliberate, with a cool, almost essayistic surface that keeps cracking to reveal something messy underneath. The downside is that Bak sometimes cannot stop herself from spelling out the thesis. We get pages of examples of animal cruelty, pages of psychological theorizing about parents and psychopaths, pages of “society crowns the powerful” that, while on point, start to feel like being lectured by a very smart friend who does not realize you already agree with them. The result is that a story that is emotionally gnarly as hell occasionally reads like an op-ed taped to a crime novel. It is still good, but you can see the scaffolding.

Petty Lies is about responsibility, class contempt, and the way violence radiates outward from “small” acts. A kid lies about who killed a dog, a rich mother humiliates a poor one, a long exhausted caregiver decides she cannot do it anymore, and suddenly there are graves everywhere. The horror engine is clever: animal torture stands in for all the bodies society decides are disposable, while the poisoned cake and the letters play out a sick moral debate over whether there is such a thing as righteous revenge when the target is a damaged kid. It leaves you wondering which is more terrifying, the possibly psychopathic son or the exhausted adults who keep choosing the cruelest possible option while telling themselves they are protecting their own. The aftertaste is sour and sticky, like you just binged a true crime podcast and realized the real monster is the culture that lets this shit slide.

In context, Petty Lies sits comfortably with the wave of dark, domestic psychological horror that asks how far parents will go and what happens when the kids are already broken, somewhere between My Sister, the Serial Killer and a particularly bleak K drama thriller. It is not a once in a decade masterpiece, but as a debut it announces a writer who knows exactly which social nerves she wants to stab.

A smart, pissed off, and often devastating crime horror novel that occasionally talks a little too much, but when it hits, it hits like a fucking brick.

Read if you are into morally fucked up narrators, unreliable letters, and kids who say the quiet part out loud.

Skip if graphic harm to animals is a hard no, even when the book is clearly raging against it.

Petty Lies by Sulmi Bak,

published November 11, 2005 by Mulholland Books.

Leave a comment