Welcome to Dreadful Digest, Vol. 4, a cozy little bonfire where grief pokes the flames and nostalgia tries to eat the marshmallows. We’re starting in the damp with Stephen Howard’s This House Isn’t Haunted But We Are, a love triangle starring him, her, and a needy bungalow that keeps sighing at the loft; think gothic cardigan weather with feelings that won’t stop creaking. Then we cross the Atlantic for Ania Ahlborn’s The Unseen, where a feral boy, a family on the ropes, and a chorus of Amber Alerts hammer home that bureaucracy is the scariest monster with a badge. Jodie Robins drags us to off-season Blackpool in The Off-Season, all carnival smiles and salt-bitten rot, a seaside fable where Punch and Judy grin like they know your browser history. We finish waist-deep in snow with Boreal, Katherine Silva’s taiga mixtape of teeth, antlers, and appetite, proof that the forest is not your friend and the outhouse has career aspirations. Grab a hot drink, lock your attic, and tell your memories to keep their hands where we can see them.

This House Isn’t Haunted But We Are: Love Triangle Featuring Him, Her, and a Needful Bungalow

Stephen Howard is a Manchester-born writer now in Cheshire, with short fiction in places like The No Sleep Podcast and Metastellar, plus a prior comic-fantasy novel (Beyond Misty Mountain) and several collections. Credentials: solid. This novella arrives via Wild Hunt’s Northern Weird Project, a pocket-sized series spotlighting eerie stories of Northern England.

A grieving couple flees to a remote cottage to weld their marriage back together, only to find the house has opinions. The narrative flips between husband, wife, and the literal house, which is less Amityville and more lonely, needful roommate with drafty bones and secrets in the loft. Even the press copy flags the three-POV braid.

This is grief horror wearing a gothic cardigan: damp, wind, rot, and that ache you can’t mop up. It toys with the “haunted house” trope by asking whether the building is haunted or the people are. The prose is clean, unfussy, occasionally lyrical, and the alternating POVs give a nice stereoscopic dread. It never bludgeons you with lore; it prefers gooseflesh by suggestion.

The book’s best idea is that architecture remembers. The house wants warmth like any widower. The couple wants absolution without confession. The result is a moorland feedback loop of need. When it leans cosmic, it whispers scale instead of screaming mythology, which fits the intimate stakes.

Strengths: the triptych narration, the humane take on haunting, and a few razor-sharp images that punch straight through the rib cage. Originality is present but not all the way cooked; the beats are familiar, if tenderly arranged. Pacing is reasonable with a brisk novella glide with a middle stretch that meanders like a lost rambler. Characters are well-sketched, though the husband’s grief monologue occasionally outshouts the wife’s arc. Scare factor: eerie more than terrifying; you’ll shiver, not shriek. As a Northern Weird entry, it’s a tidy, melancholy riff rather than a revelation.

Recommended for: Readers who like their hauntings with tea, tears, and a passive-aggressive cottage.

Not recommended for: Adrenaline goblins demanding demon latrine explosions, or anyone whose loft just made a funny noise and who would like to sleep again this decade.

Published April 3, 2025 by Wild Hunt Books

The Unseen: Amber Alerts And Emotional Support Pinot

Ahlborn is a dependable name in modern horror, known for domestic dread and bad things happening to families. Think novels like Seed and Brother. She writes clean, fast, and mean.

In rural Colorado, Isla is drowning in grief when a silent, feral boy materializes at the edge of her property. The family fosters him, names him Rowan, and quickly collides with the mystery of where he came from and what the hell he is. Missing kids, Amber Alerts, and a chilly state bureaucracy frame the horror while Rowan’s nonverbal strangeness turns the home into a pressure cooker.

This is grief horror braided with the feral-child myth. Ahlborn uses the boy as a walking Rorschach: the parents project need, guilt, and salvation onto a kid who does not speak back. The recurring news alerts read like a Greek chorus for American panic. Symbolically, Rowan is the hole grief leaves behind made flesh. Prose is uncluttered, sometimes starkly effective, with occasional needle-stab images that land.

The novel’s mean little observation is that American families will spiritualize anything rather than look directly at their pain. Isla wants a miracle; the system offers forms; the truth rots in the woods. When the book leans into that moral murk, it works.

- Originality: The feral-child angle grafted onto missing-children paranoia is fresh enough, but the story often retreats to familiar beats.

- Pacing: Front third hums, middle meanders, finale tidies more than it detonates.

- Characters: Isla is sharply etched; Luke and teen son August feel real if occasionally sitcom-loud. Secondary kids blur.

- Scary? Unsettling, not pants-wetting. You’ll squirm more than scream.

- Craft: Clean structure, strong setup, a few striking set pieces; the big answers feel half-brave.

Competent, readable, occasionally chilling, ultimately not a banger. You’ll finish it, nod, and move on.

Recommended for: Parents who alphabetize the spice rack to avoid crying, fans of quiet dread and state paperwork horror.

Not recommended for: readers whose idea of comfort is doomscrolling Amber Alerts before bed and then wondering why the forest keeps knocking.

Published August 19, 2025 by Gallery Books

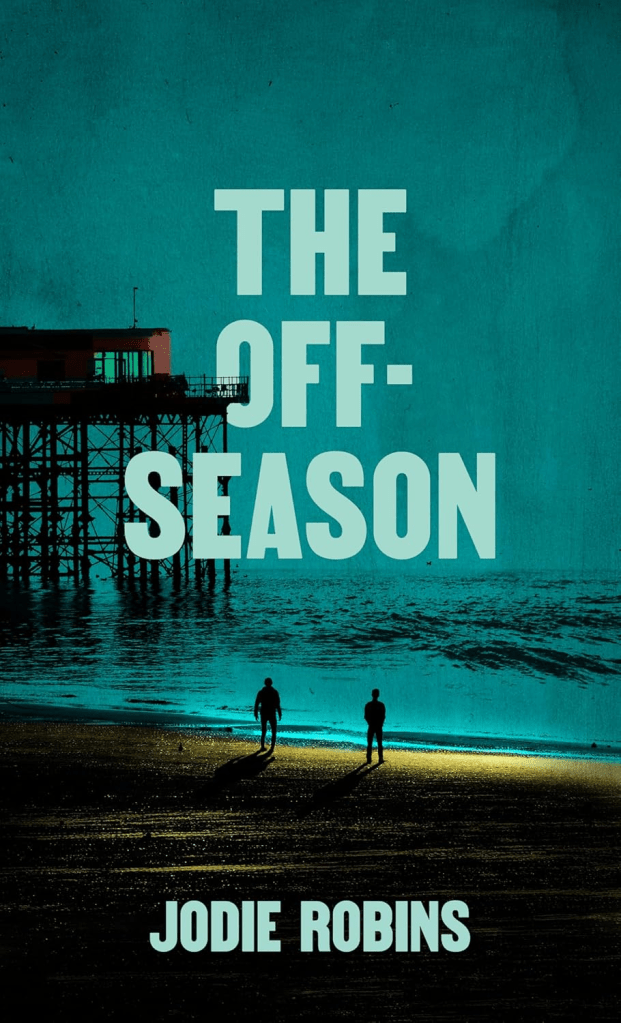

The Off-Season: Blackpool Smiles With Too Many Teeth

Jodie Robins drops a wintry little gut-punch set in Blackpool, that grand old seaside that looks glorious on postcards and terminal on a Tuesday in January. The novella is yet another entry from Wild Hunt’s Northern Weird Project, which already tells you the vibe: salt, rust, and ghosts dressed as memory. Robins writes with a crisp line that lets the cold do the talking.

Tommy and his dad, Al, are grinding through the days around a friend’s funeral when a vintage charabanc rattles into town like a carnival that forgot what month it is. Stalls bloom along the dead promenade, Punch and Judy start cackling as if they’ve unionized, and the locals smile the wrong kind of smile. No spoilers, but the town doesn’t so much wake up as get replaced by a cheerier, hungrier version of itself.

The book’s engine is grief welded to economic decay. Blackpool is a body out of season, and the past arrives offering cotton candy and answers it does not have. The carnivalesque visitors work as a funhouse mirror: community rituals that should console instead cannibalize. A bus named Dorothy might as well be labeled nostalgia, do not feed, will bite. Robins knows that the most dangerous hauntings are the ones you ask for.

As a reading experience, it’s competent and enjoyable with flickers of something sharper. The originality sits in the seaside apocalypse by way of weaponized nostalgia; the mechanics of the weird stay coy, which keeps the mood chilly but occasionally leaves the stakes fuzzy. Pacing is mostly steady, a brisk walk along the front with a few pauses to stare at the gray water. Tommy and Al carry the heart; their prickly father–son banter feels lived in, while the supporting cast mostly functions as atmospheric chorus. Scare factor lands in the uncanny zone. You shiver, you smirk, you do not turn on every light.

It’s good, not great: a salty elegy with a grin full of splinters. I wanted one more gear, one nasty choice that pushed the fable into legend. Still, the wind cuts, the jokes bite, and the last image hangs around like sea mist.

Grief throws a carnival on a dead-cold Blackpool day. Strong atmosphere, sly humor, a memorable duo, and a weird that winks more than it devours. You’ll feel the chill and wish it stabbed deeper.

Recommended for: Readers who like their horror briny, their jokes bitter, and their ghosts disguised as memories with terrible customer service.

Not recommended for: Thrill-seekers demanding chainsaws, or anyone who thinks Punch and Judy is adorable and won’t mind it grinning at them after midnight.

Published June 26, 2025 by Wild Hunt Books.

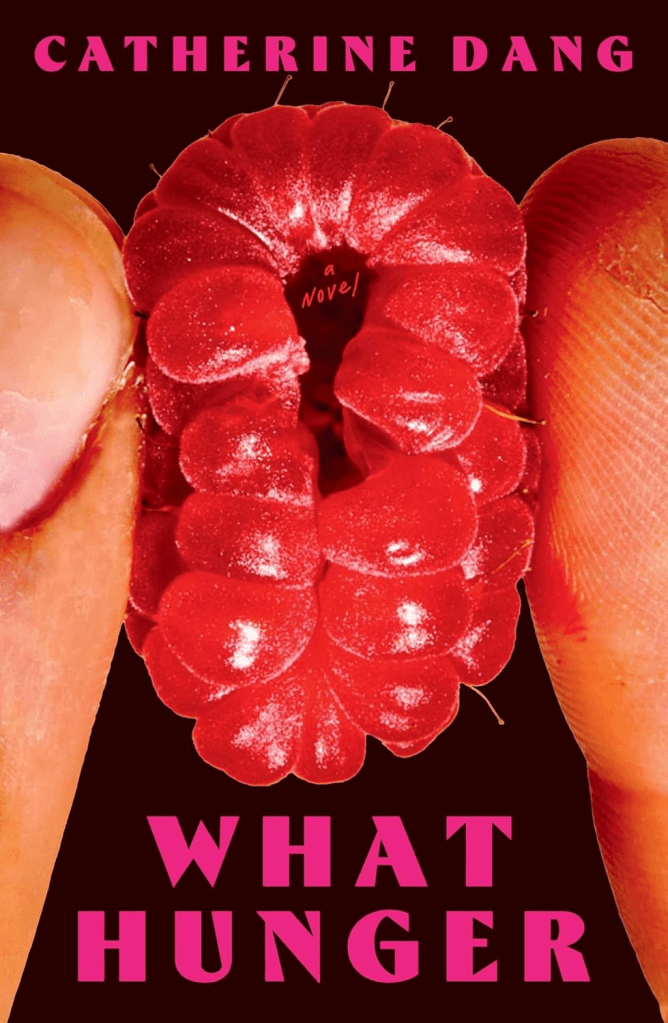

What Hunger: The Squirrel Saw Too Much

Catherine Dang, author of the buzzy debut Nice Girls, turns to a grief-soaked, immigrant-family coming-of-age that keeps staring at the highway and asking why it always eats first. We follow Vietnamese American siblings Veronica and Tommy through a “Big Summer” that curdles into aftermath: hot gyms, family food, neighbors who trap wildlife like it’s a hobby, and a town that can’t mind its own business. The opening chapters build a lived-in world of sweat, sniping, and love, then yank the floorboards. The book is less monster mash, more human wreckage with teeth.

Thematically, Dang goes hard on appetite. Hunger is literal and social and moral. People hunger for safety, for status, for forgiveness, for someone else to be wrong so they can feel right. The squirrel in the trap, bloody and frantic, becomes the book’s grim little mascot: panic as a worldview. The writing is clean, heat-shimmer exact, with sharp domestic detail and dialogue that sounds like real family warfare. When the prose slows to watch a gesture or an object, it lands with the pop of a camera flash and the sting of salt.

Meaning wise, this is a novel about how grief colonizes the body, and how diaspora households metabolize rage. It pokes at memory, masculinity, and the way institutions smile while handing you a form. There is power here. There is also drift. The middle lapses into samey scenes of simmering anger and parental stonewalling, and the larger machinery of the plot never clicks into something feral enough to match the title.

Strengths: sticky atmosphere, unforced cultural texture, a sibling bond that feels painfully true. Originality sits in the vantage point and the granular domesticity, not the arc. Pacing is workable but baggy in the gut. Characters are sketched with care, though side players blur. Scary? Not really. It is unnerving and sad, with a few images that will not quit, but horror fans looking for dread spikes will get a slow ache instead.

Good book, not a gut-punch classic. Competent craft, flashes of brilliance, too much idling.

Intimate grief novel in a hot American summer. Razor clean prose, vivid family dynamics, resonant symbols. Also meanders, undercuts its own menace, and never quite turns the screw far enough to draw blood. Solid read, not a bruiser.

Recommended for: Readers who season their fiction with fish sauce and spite, and think a trapped squirrel is a thesis statement.

Not recommended for: Readers who treat grief like a checklist, prefer their families neat and silent, gag at fish sauce, and would like the squirrel, the summer heat, and everyone’s bad decisions to stop making eye contact with them.

Published August 12, 2025 by Atom.

Boreal: Taiga Tourism Board Says “Please Don’t Visit”

Katherine Silva‘s Strange Wilds Press takes to the subarctic as she curates twenty-two wintry nightmares where the trees are not your friends and the past keeps chewing. It’s a themed buffet of isolation, grief, and weird folklore set across the boreal belt, with a table of contents that swings from creature terror to eco-gothic to outright human rot.

No spoilers, but a few standouts: E. M. Roy’s “Cabin Creatures” gives us a wendigo-adjacent brute and a cabin that remembers, then answers, which is metal as hell. “Every Mask, Another Cask” (Akis Linardos) turns an inn into a masquerade of hunger and identity; it’s boozy, feral, and oddly tender. Vincent West’s “Gathering of the Dead” is the gut-kick, a feminist folk-monster assembled from missing women that turns local “monster” lore back on the men who benefit. Jon Gauthier’s “Nightmare in Kettle Park” features the most upsetting al fresco cooking scene I’ve read this year; you will never trust an outhouse again. The intro also name-checks journeys like Santos’s “Cold White Teeth” and Ally Wilkes’ alpine dread, framing the anthology’s mission as survival in a biome that does not care if you’re having a moment.

The throughline is appetite. People, places, and things want: warmth, absolution, meat, meaning. Silva’s theme works because the taiga itself becomes a character, a long, needling silence that judges. Symbolism skews tactile: antlers shedding meat, bone-built beasts, carnival-bright auroras. The prose across authors stays crisp and cold, rarely fussy, often barbed.

Does it rip? Sometimes. Originality shows up in concept and image, but a handful of mid-list entries wobble or end on polite fades. Pacing is what you expect from anthologies: bangers, then a snowdrift, then another banger. Character work varies, though the best pieces sketch people fast and bleed them faster. Scare factor lands more uncanny than pants-ruining, with two or three legit disturb-your-sleep moments. Net result: competent, enjoyable, a few keepers, not a canonizer.

This is a wintry horror mixtape of grief, hunger, and hostile trees. Several excellent stories, a few shrugs, strong sense of place, and enough nightmare fuel to salt your driveway. You’ll shiver, highlight lines, and wish the middle third hit as hard as the openers and closers.

Recommended for: Readers who think a nice vacation involves snow, knives, and unresolved ancestral curses.

Not recommended for: Folks who call 50 degrees “freezing,” hate pine, and prefer their bathrooms unoccupied by chefs with briefcases.

Published February 25, 2025 by Strange Wilds Press.

Leave a comment