Half a century after its original publication in 1975, Joan Samson’s The Auctioneer remains a haunting and under-appreciated classic of American horror fiction. A novel that drips with dread from its opening pages, The Auctioneer is a slow-burning, psychological nightmare that burrows into the reader’s subconscious and refuses to leave. Its depiction of small-town New England’s unraveling under the influence of a charismatic interloper is as timely now as it was in the 1970s. Samson’s only published novel before her untimely death, The Auctioneer is a masterclass in controlled storytelling, a parable of creeping authoritarianism disguised as small-town charity, and a deeply unsettling meditation on the fragility of rural life.

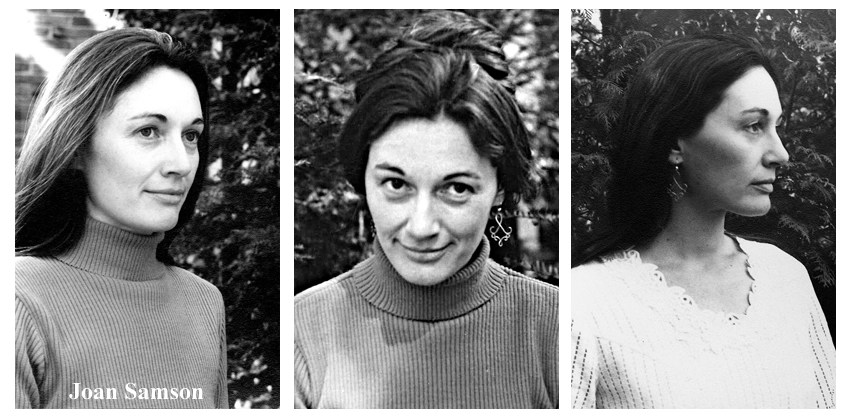

Joan Samson’s legacy is a tragic one. She died of brain cancer in 1976, just a year after The Auctioneer was published, leaving behind what is both a singular and singularly unnerving work. A recipient of a grant from the Radcliffe Institute, Samson wrote The Auctioneer with a keen sense of place and an intimate knowledge of the rhythms of rural life. She was not a writer who dabbled in horror for the sake of sensationalism; rather, she wielded suspense as a scalpel, carving out an unrelenting portrait of a community slowly waking up to its own destruction. Though she never had the chance to publish another novel, her work endures as a cautionary tale about power, greed, and the loss of autonomy.

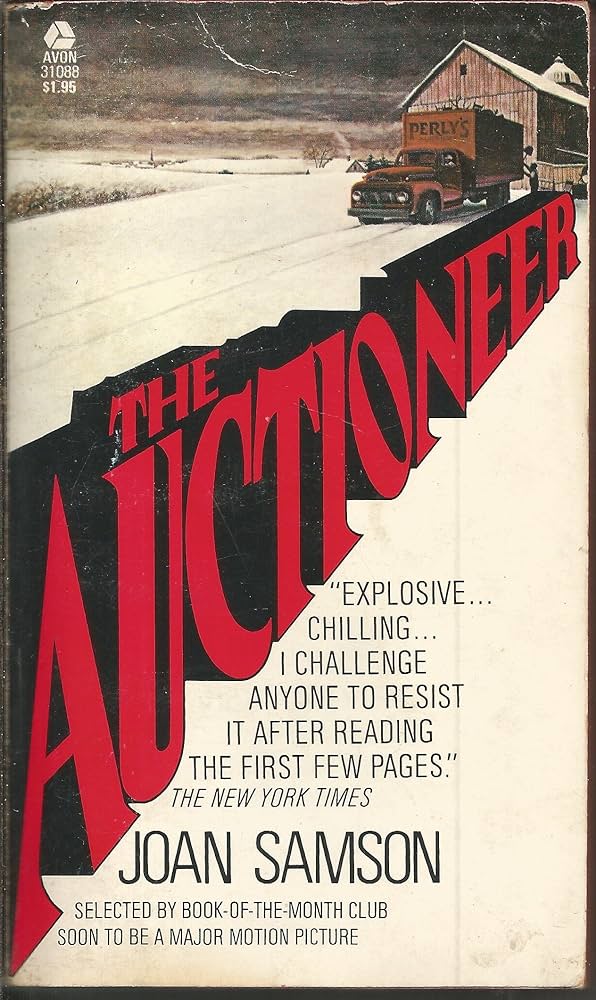

Set in the fictional town of Harlowe, New Hampshire, The Auctioneer follows John and Mim Moore, a hardworking farming couple, and their daughter Hildie. Their quiet existence is disrupted when Perly Dunsmore, a slick, fast-talking auctioneer, arrives in town and begins orchestrating community-wide auctions, purportedly to help raise money for the town’s police force. At first, the Moores and their neighbors are happy to donate small, seemingly useless items. But as Perly’s influence grows, his demands become increasingly insidious. First, it’s a few old wheels, then a plow, then family heirlooms, livestock, and eventually, even their land and homes. The town finds itself trapped in an inexorable cycle of compliance and fear, unable to resist Perly’s persuasion—or the mounting violence that follows those who do.

As the novel progresses, the noose tightens around Harlowe. The town’s leadership is complicit in Perly’s schemes, and the Moores, like their neighbors, are caught in a slow-motion disaster, unable to push back without severe consequences. The final moments of the novel, in which the remaining townspeople are left stripped of nearly everything, underscore Samson’s ultimate message: evil does not always announce itself with violence. Sometimes, it arrives with a smile, a handshake, and the promise of something better.

At its core, The Auctioneer is a parable about power, submission, and the ease with which communities can be manipulated. While its most immediate reading is as a critique of unchecked capitalism and the commodification of rural America, it is also an eerie precursor to modern anxieties about authoritarianism, the erosion of individual rights, and the dangers of mass complacency. The town of Harlowe is not taken over in a sudden coup; it is lost piece by piece, in what feels like an inevitable march toward destruction.

Samson also explores the psychology of fear and compliance. The Moores, like the rest of the town, know that something is terribly wrong, but they rationalize, delay action, and convince themselves that their sacrifices are temporary. The novel forces readers to ask themselves how long they would wait before resisting, and whether they too would be lulled into passivity by a figure as cunning as Perly Dunsmore.

The titular auction serves as the novel’s most powerful symbol. Traditionally, an auction is a transaction between willing participants, a fair trade where items are exchanged for value. But in The Auctioneer, the auctions are a mechanism of coercion and theft. What begins as voluntary community participation morphs into an unrelenting system of control, a process by which Perly slowly strips the town of everything it holds dear.

Perly himself is a symbol of corruption masked as progress. He presents himself as a benefactor, a man bringing prosperity to Harlowe, yet he is nothing more than a parasite, feeding off the town’s resources while offering nothing in return. His dog, Dixie, trained to perform tricks and feign submission, serves as a chilling parallel to the people of Harlowe, who are manipulated into obedience through charm and intimidation.

Samson’s prose is deceptively simple, but her control over tension and atmosphere is extraordinary. She does not rely on cheap scares or supernatural elements; instead, she cultivates a feeling of encroaching dread through precise, economical storytelling. Every interaction in The Auctioneer carries an undercurrent of menace, even in the seemingly mundane moments. Samson’s ability to evoke setting is also remarkable—Harlowe is vividly realized, a New England farming town that feels wholly authentic, making its downfall all the more tragic.

The novel’s pacing is deliberate, its horror cumulative. Readers may not recognize the depth of the town’s loss until it is too late—just as the characters do not. This slow-motion destruction is what makes The Auctioneer so disturbing; there is no moment of cathartic, explosive violence, only a suffocating descent into despair.

One of the novel’s greatest strengths is its realism. Unlike many horror novels of its era, The Auctioneer does not rely on the supernatural, yet it is one of the most terrifying books of the 20th century. Its depiction of power, coercion, and collective inaction resonates just as strongly today as it did in 1975.

Some may find its pacing too methodical, and the relentless bleakness can be exhausting. Additionally, the character of Mim, while well-drawn, sometimes feels overshadowed by John’s perspective, despite her being just as integral to the story. A deeper exploration of her internal struggles might have enriched the narrative further.

Fifty years after its release, The Auctioneer remains an essential, deeply unsettling novel that deserves a place among the greats of American horror fiction. It is a book that forces readers to reconsider the nature of power, the insidiousness of greed, and the terrifying ease with which a community can be dismantled. Despite its relative obscurity compared to other horror novels of its time, The Auctioneer deserves to be rediscovered by a new generation of readers. It is a quiet masterpiece, one that does not scream for attention but instead whispers in the dark, unsettling and unforgettable.

Published 1975

Leave a comment