Lindsay King-Miller has been a sharp, funny, unflinchingly honest voice in queer culture for a long time. Her nonfiction book Ask a Queer Chick (Plume, 2016) came out of a long-running advice column and cemented her knack for straight-talk about messy human realities. She’s also a poet and essayist with bylines across mainstream and indie outlets, and in recent years she’s turned hard toward horror (The Z Word, 2024) before delivering this gnarly, heartfelt exorcism of family and faith.

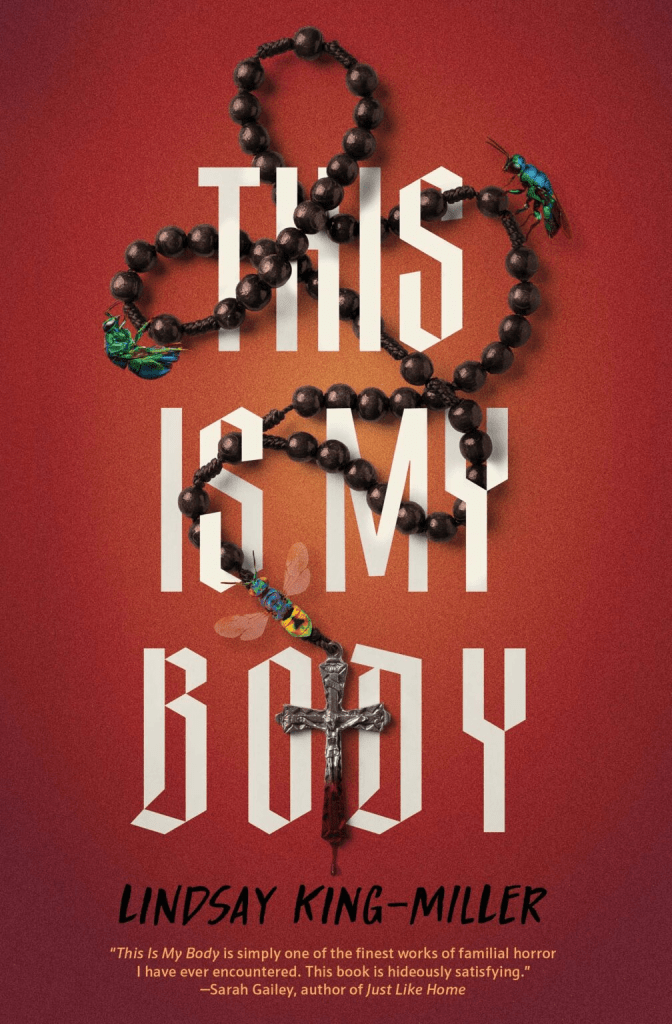

Brigid is a lesbian single mom running a mountain-town occult shop, the Tenth Muse. Her eighth-grader, Dylan, has turned brittle and withdrawn and, out of nowhere, socked her best friend in the face at school. Brigid’s old wounds don’t help: she grew up under the iron fist of her uncle, Father Angus, an off-brand inquisitor who once presided over a back-room exorcism that branded her idea of “holiness” with pure terror. When Dylan grows fixated on an obsidian scrying mirror and starts acting like something is looking out from behind her eyes, Brigid is forced to reckon with the past she fled, the faith she junked, and the possibility that the monster in her house is equal parts demon, memory, and bloodline. The opening exorcism image (girl handcuffed to a bed, a priest forcing holy water down her throat) tells you exactly what kind of damage this world calls “love.”

From there, King-Miller paces between the present (Dylan’s spiral; Brigid’s stubborn caretaking) and the past (Brigid’s first crush, Alexandra “Zandy” Mulligan, and the church-steeped control that warped their lives). The school incident that lights the fuse is handled with needle-point details that feel painfully true to middle school politics and adult condescension. In Brigid’s shop, Dylan’s fascination with that glossy black disc—“It lets you see beyond the surface of things”—is the novel in miniature: how do you live with what you can’t stop seeing?

This is religious trauma horror done right: not a morality play, not an atheist victory lap, but a thorny argument about authority, desire, and the stories families build to survive themselves. The central metaphor is the body, who owns it, who polices it, who gets to call the shots in it, and King-Miller uses the possession framework to pry at bodily autonomy with a chisel and a blowtorch. The obsidian mirror isn’t just a spooky prop; it’s what happens when a kid tries to make sense of secrets adults are too cowardly to name. The mirror invites; it reflects; it punishes; it refuses to lie. (The “don’t dig up secrets unless you want yours exposed” warning lands like a curse.)

King-Miller’s prose is wired and musical, smart-mouthed without being glib. She’s good at rooms: a principal’s office that shrinks you by design, those terrible retail-witch shelves where crystals sit like weaponized self-help, a mountain-town sunset you can’t see because the storefront turns into a mirror and throws your face back at you. The voice has humor, but it’s defense-mechanism humor: the kind of jokes you make while prying your fingers out of a trap. And when she wants to go for the jugular, she does, with body horror beats that feel both occult and biological.

This Is My Body is ultimately about inheritance. Not just the easy “cycles of abuse” tagline, but the practical engineering problem of how to re-route power when your whole childhood taught you that obedience is salvation. Brigid’s arc is not “believe again” or “disbelieve harder,” it’s “what does care look like when belief has been used to hurt you?” The novel posits two bad gods: the literal demon that may or may not be in Dylan, and the institutional god that definitely is in Father Angus and in the rituals that excuse him. To love a child inside that crossfire is to pick a third way (messy, queer, syncretic, full of contradictions) and the book insists that’s the only honest miracle.

It’s also a romance with time: Brigid and Zandy’s adolescent tenderness (the secret language of hands, the first electric kiss under a tree) shows what was stolen. When Zandy reenters as an adult, the book dares to imagine adult queer joy that isn’t sanitized or apolitical. The exorcism template becomes a reclamation template. If a priest can say “this is my body” while denying you yours, watch what happens when you say it back.

Strengths

- Voice and character. Brigid is fallible and fierce, a mother who loves hard and still snaps at the wrong moment, then tries to fix it with coffee and apology. Dylan reads like a kid on the edge of a cliff, scabbed lip, bitten nails, running out of language, which is exactly where horror belongs. (See Dylan’s flat “No” as choir is forced on her and tell me you didn’t flinch.)

- Worldbuilding via small stakes. A principal’s weaponized politeness; an obsidian mirror demo from a too-cool college clerk; the smell of a shop that sells packaged transcendence, these micro-threats snowball into a macro-haunting.

- Theological bite. The book understands Catholic performance and its shadow twins (New Age aesthetics, self-help pieties) and lets them scrape against each other until they spark. It doesn’t pick a side; it demands responsibility.

Critiques

- A couple of middle-stretch loops. The investigation circles the same anxieties once or twice too often; you can feel the story catching its breath before the next descent. The flipside is that the repetition sells how obsession works.

- Angus as the big bad… mostly. He’s chilling, but at times he teeters on being a symbol more than a man. Then again, that’s the point: patriarchy loves a mask.

Originality: It’s not reinventing possession so much as refusing to play by its church-approved rules. Instead of priest vs. devil, we get mother vs. machine, where the machine is a culture that treats girls’ bodies as battlegrounds. That angle and the queer, working-class specificity feel fresh as cut stone. (The book’s own materials pitch it as “a queer, thorny possession tale,” which is exactly right.)

Pacing: After a tight, nasty prologue, the book simmers (family drama and occult hints) before it boils. I liked the slow heat. When it pops, it pops red. The chapter architecture gives you just enough oxygen, right up until it yanks the air away. (The table of contents promises an epilogue; the structure pays off. )

Characters: Brigid and Dylan are drawn with granular empathy; Zandy has dimensional charm; even the shop clerk, Cypress, sticks in your head. Angus is an excellent hate-totem. The side cast, principal, classmates, townies, do a lot of atmospheric work.

Scare factor: It’s more suffocating dread and bodily wrongness than jump-scare carnival. The horror lands in kneecap-level realities: the way authority handles a “problem girl,” the way faith gets under your skin and won’t come out, the way love gets mean when it’s afraid. The set pieces are gnarly enough to make an exorcist blush, but the scariest moments are intimate.

TL;DR: A queer possession novel that swaps priestly heroics for a mother’s stubborn love and a teenager’s haunted autonomy. King-Miller turns religious trauma into sharp, tender body horror and lets the characters bleed honestly. It’s gnarly, funny, pissed-off, and ultimately generous. An exorcism that makes room for a future.

Recommended for: Readers who have complicated feelings about church basements, moms who would fight a demon with a coffee mug and a coupon for sage, queer kids who ever stared into a bathroom mirror and saw it stare back, and anyone who knows middle school is the real hellmouth.

Not recommended for: People who think an exorcism is just CrossFit with holy water, principals who weaponize “Mizz,” clergy who treat “this is my body” like eminent domain, and anyone who believes an obsidian mirror is only good for checking your bangs.

Published August 5, 2025 by Quirk Books.

Leave a comment