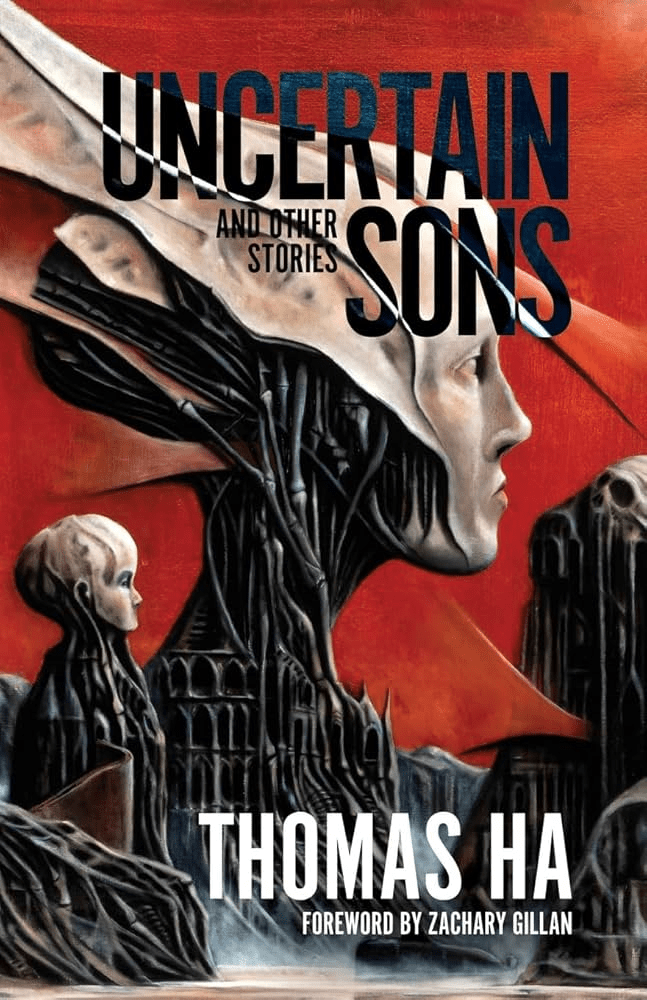

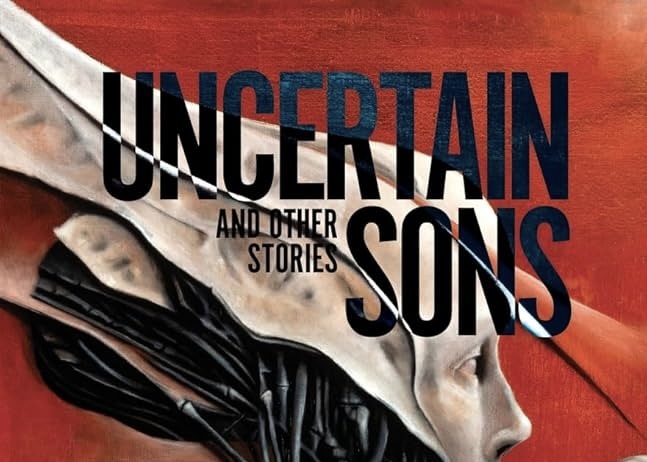

Thomas Ha writes like someone smashing a viewfinder with a ruby-handled hammer so you’re forced to look at the world from three angles at once. Uncertain Sons and Other Stories is weird horror tuned for adult nervous systems: intimate, prickly, tender, then casually apocalyptic. It’s also a banger of a debut collection from Undertow.

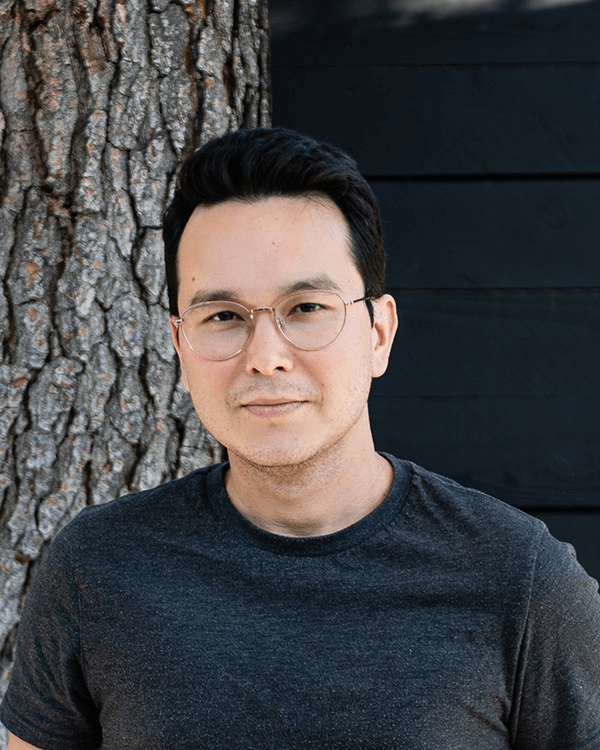

Ha is a short-fiction assassin whose work has picked up a small museum’s worth of nominations. He’s been up for the Nebula, Ignyte, Locus, and Shirley Jackson, with appearances in Clarkesworld, Lightspeed, Beneath Ceaseless Skies, Best American Science Fiction & Fantasy, and more. He grew up in Honolulu and lives in Los Angeles with his family. “Window Boy” is his best-known story, reprinted in Best American SFF 2024 after being a finalist for the Nebula, Ignyte, and Locus.

Twelve stories orbit a loose future history where collapse is less an event than a climate. Rich families hide in fortified houses while grackles the size of streetlights roost on utility poles. People wear “amp-glasses” to filter each other into brandable themes. Balloons are not balloons. Homes are sometimes safe and sometimes lies. The capstone novelette, “Uncertain Sons,” is original to this volume and closes the book with an action-forward, fairy-tale-logic quest that detonates into a quietly devastating flashback.

Standouts:

- “Window Boy,” a privileged kid peering through a screen at the boy outside and trying not to see what’s real.

- “Cretins,” a Ferrier’s-syndrome narrator stalked by a “hound,” flipping the predator script in a way that will make you grin and then feel bad for grinning.

- “The Brotherhood of Montague St. Video,” a cult of physical media and grief that doubles as the collection’s philosophical center.

- “Balloon Season,” in which domestic fortification meets a sky full of wrong.

The foreword nails it: Ha writes about occultation in the verb sense, what we hide from ourselves to keep functioning. His characters choose how to see, or not see, the broken world. That’s the core engine here.

Houses are altars and blindfolds. Hospitality matters until it doesn’t; the Greek code of xenia gets invoked, then violated, and the violation is treated as true monstrosity. The walls we build to “keep it out” often keep us from seeing the rot in the living room.

Ha also sneaks a color-coded leitmotif through the book. Yellow flickers as caution, cowardice, and glitch: UI states for not-quite-human minds, a trickster named Yellow Eyes, medicinals that destabilize a mind, and camouflage that keeps viewers from seeing what’s in front of them.

Formally, he’s anti-infodump. You learn the world by catching the corners of things as the light moves over them. It’s pointillist worldbuilding with lived-in, naturalistic prose that refuses to hold your hand, which is exactly why it works.

The collection also contains a quietly linked triptych: “House Traveler,” “The Sort,” and “Uncertain Sons.” Read them as a wobbling line about walls, seeing, and the myth that separation is real. The author flags those three as the core connective tissue.

Ha is writing about the moral ergonomics of attention. If you lower the filter too far, you drown; if you keep it too high, you become a cartoon of yourself. “Uncertain Sons” reframes the book as a meditation on how we carry fathers and sons through extinction events without turning them into talismans. It’s elegy smuggled inside a creature feature, and it hits hard because the monsters are never as bad as the compromises.

Strengths:

- Atmosphere you can chew. Even the quiet stories hum with threat.

- Original creature logic: balloons, grackles, amp-glasses, and coded pharmacology feel weird in the useful sense.

- Emotional honesty without melodrama. Several endings land with surgical sadness.

Critiques:

- A couple pieces risk feeling like variations on the same macro-move of withholding. I like ambiguity, but there are moments where the opacity isn’t additive.

- “The Mub,” with its deliberately atavistic voice, may read like a tonal detour if you’re here for the near-future dread. That’s taste, not sin.

- One or two mid-book stories sag in the center as they orbit their big conceit.

Originality: High. This isn’t “Netflix-pitch horror.” It is its own nervy ecosystem.

Pacing: Mostly excellent. Ha alternates short adrenalin pops with slow dread burners, then spikes the landing with the title novelette.

Characters: Fully human in a broken physics. Even when the world is funhouse-mirrored, the interiority is straight.

Is it scary? In the marrow, yes. Less jump scares, more existential tightness. “Cretins” in particular weaponizes vulnerability until the blade flips.

Prose quality: Clean, measured, deceptively simple. No purple frosting, just knives.

This belongs near the top of your 2025 shelf if your shelf likes the weird. It is bold, atmospheric, thematically sharp, and not trying to sell you a streaming deal. Only the occasional over-elliptical move and a couple of tonal swerves keep it from perfect.

TL;DR: A razor-precise, humane, and deeply weird collection about the things we refuse to see so we can keep living. Houses lie, balloons hunt, screens soothe, and fathers and sons try to find each other anyway. Ha refuses cozy answers and earns your dread the hard way.

Recommended for: Readers who think hospitality is sacred until a monster drinks the coffee, parents who barricade their feelings as carefully as their windows, and anyone who smiles when a “balloon” is the scariest thing on the page.

Not recommended for: Readers who need the apocalypse explained in bullet points, panic when balloons don’t behave, refuse to take off their amp-glasses at dinner, file complaints when grackles get mythic, think xenia is optional, prefer the Brotherhood’s back room to eye contact, and won’t look Yellow Eyes straight on.

Published September 16, 2025 by Undertow Publications.

Leave a comment