Wendy N. Wagner is editor-in-chief of Nightmare and on the Hugo-winning Lightspeed team. She’s also the writer of The Deer Kings, The Secret Skin, and the Locus-bestselling An Oath of Dogs, with award-nominated short fiction to spare. She lives in Oregon, runs trails, and evidently stares at trees until they confess.

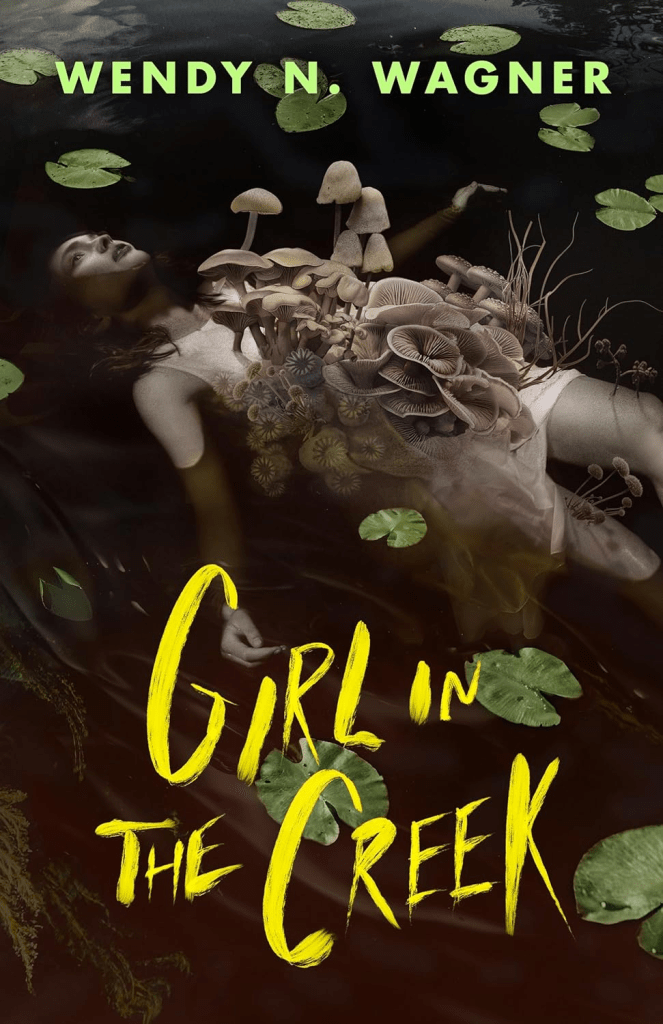

Erin Harper, a travel writer with a grief crater where her brother Bryan used to be, heads to Faraday, Oregon to cover rafting and hot springs for Oregon Traveler while quietly sniffing around the town’s run of missing persons. The first face she meets is on a flyer: Elena Lopez, a server at the local brewery who up and vanished. Erin bunks at a stately guest house owned by Olivia Vanderpoel, matriarch of a family whose shadow touches everything in Faraday, from the burned-down resort hotel to the springs themselves. She teams up (uneasily) with friends, Dahlia and Jordan, plus coworkers Hari and ultralight-gear power couple Kayla and Matt, to poke at Faraday’s rot. The poking leads into the woods, toward the ruins of Hillier and a mill wheel, where history, bodies, and something older than logging camps start answering back.

Also stalking the margins: Erin’s unresolved grief over Bryan, needling her via an old postcard from this very visitor center, whose “nothing to see here” smile hides a watcher in the background.

This is eco-horror with a mycelial brain and a grudge. Wagner alternates human viewpoints with the perspective of a forest-scale network, “the Strangeness”, that hums through coyotes, trees, and rot, spreading like gossip after last call. The opening chapter, seen through a coyote, sets the tone: a body dragged from an adit to a creek, nature not as backdrop but as agent. We hear the network’s music ripple across living things; the forest isn’t scenery, it’s chorus and conductor.

Wagner’s symbolism is thick with fungi. A late-book riff recasts mycelium as a distributed intelligence capable of partitioning mind across objects, which doubles as a metaphor for grief’s sprawl: how a lost person gets smeared through places and keepsakes until the world itself is haunted. The book even names a central node, Haven, like a wounded brain stem pulsing under the town.

Culture-rot and extraction run parallel: the Vanderpoel empire (hotel, hot springs, minerals) sits on Faraday like a cover stone; the town’s origin myth includes a 1907 meteor and a resort that eventually burned, leaving relics and resentments. Wagner folds in small-town misogyny via the Steadman clan, the kind of men who’ve “harassed” generations like it’s a family business. Meanwhile, Olivia Vanderpoel’s house hangs with her missing son’s powerful, flesh-and-forest art, cracking open a vein of maternal grief and body-into-land imagery.

Prose-wise, Wagner toggles clean realism with wet, sensory horror. You get Pacific Northwest textures (the brewery, visitor center, and mud-slicked switchbacks) then sudden, squelchy intrusions that feel like stepping on a deer kidney. Which, sometimes, you are.

At its best, Girl in the Creek argues that the world is not merely alive but plural. The Strangeness isn’t “evil” so much as non-anthropocentric: it prefers conversion to companionship, a vibe summed up in the coyote’s comfort that it’s “better Strange than human.” That’s chilling as a thesis statement for the Anthropocene. The book’s grief engine (Erin’s brother, the town’s missing, a mother’s absent son) makes a convincing case that loss feeds ecosystems, social and literal. The postcard watcher gag is perfect: the land looks back.

Wagner also jabs at who gets listened to. Erin’s a freelancer. Hari’s a true-crime podcaster. Locals like Jordan and Dahlia know the terrain. The Steadmans are protected idiots. Deputy Duvall is that overworked small-town cop trying to keep order while the ground literally opens. There’s a grimly funny scene where our crew reports being shot at near Hillier Creek and the bureaucracy shrugs like it’s Tuesday, which says plenty about rural policing and power.

Strengths

- Setting with teeth. Faraday feels lived-in: the burned resort, the “owned by Vanderpoel” everything, the B&B with Addams-Family fencing and weird statuary.

- Nature’s POV. The Strangeness chapters sing. Opening on the coyote is a flex, and the network hum is creepy in a slow-fungus way.

- Atmospheric horror. A house that smells wrong, curtains drawn, heat cranked too high. Wagner knows how to make you taste mildew.

Critiques

- Character depth is uneven. Erin and Dahlia feel human. Jordan works. But the REI power couple sometimes read like catalog cutouts, exactly how the prose frames them. Kayla eventually gets interesting for reasons I won’t spoil, but Matt never rises above “smiling halogen fiancé.”

- Pacing wobbles. The early sections marinate nicely; the last act becomes a sprint over slick rocks with exposition trying to keep up. The “distributed mind” idea rules, but its delivery leans tell-y in the crunch.

- Human villains vs. nonhuman agency. The Steadmans are believably awful, but sometimes the book’s human monster thread feels small beside the cosmic mold, which blunts moral stakes when the fungus takes center stage.

Originality: High concept executed with sincerity. Mycelial hive-mind eco-horror isn’t common in mainstream releases, and Wagner gives it biological heft.

Pacing: Middle acts are confident, strolling through Faraday’s rot; the finale is kinetic but chaotic. Think river rapid you survive but still swallow a quart of water.

Characters: Erin’s grief arc anchors things, Olivia’s art and reserve scratch nicely at class and loss, and Jordan/Dahlia bring local oxygen. Kayla becomes compelling late; Matt remains a handsome lamp.

Scare factor: Not “sleep with the lights on,” but persistently unnerving. Bodies move where they shouldn’t, rooms breathe damp, and the forest thinks in chords you can almost hear.

Girl in the Creek is bold eco-weird with Oregon mud under its nails. It’s atmospheric, smart about grief, and periodically metal. It’s also uneven in the home stretch and doesn’t fully land its people.

TL;DR: Earthy, fungal eco-horror where a mycelial network plays God and Faraday, Oregon pretends it’s fine. Great atmosphere and ideas, uneven characters, and a finale that sprints faster than it sticks the landing. Weird enough to recommend to the adventurous, not sharp enough to evangelize.

Recommended for: Hikers who whisper “sorry” to mushrooms before kicking them off logs, grief goblins who want the forest to talk back, and anyone who smiled at the idea of a coyote as an accessory to a cosmic compost heap.

Not recommended for: Gear-catalog couples who think a Patagonia shell can stop a sentient mycelium, small-town abusers, and readers who insist their horror never gets damp, dirty, or has the audacity to hum.

Published July 15, 2025 by Tor Nightfire.

Leave a comment