Welcome back to Dreadful Digest Volume 3, the buffet where your conscience goes to die and the pies are definitely not vegan. Tonight’s menu: a Victorian dossier of blood and whispers where nuns hoard secrets like relics and Mrs. Lovett’s ghost hovers over a stack of sticky letters; Bogotá Gothic absolutely marinated in incense, condors, and institutional guilt, with a waterfall hotel that wants your soul and your luggage; a slick true-crime grief machine that starts at a rest stop hot dog and ends with you side-eyeing every bystander in your life; a creaky manor tale that promises banshees but mostly delivers marital therapy with extra ravens; and a social-media splatterfest that asks if viral fame is worth your humanity, then shrugs and films the answer. Grab a fork, sinners. We’re carving into history, hypocrisy, and whatever the hell that thing on your feed was.

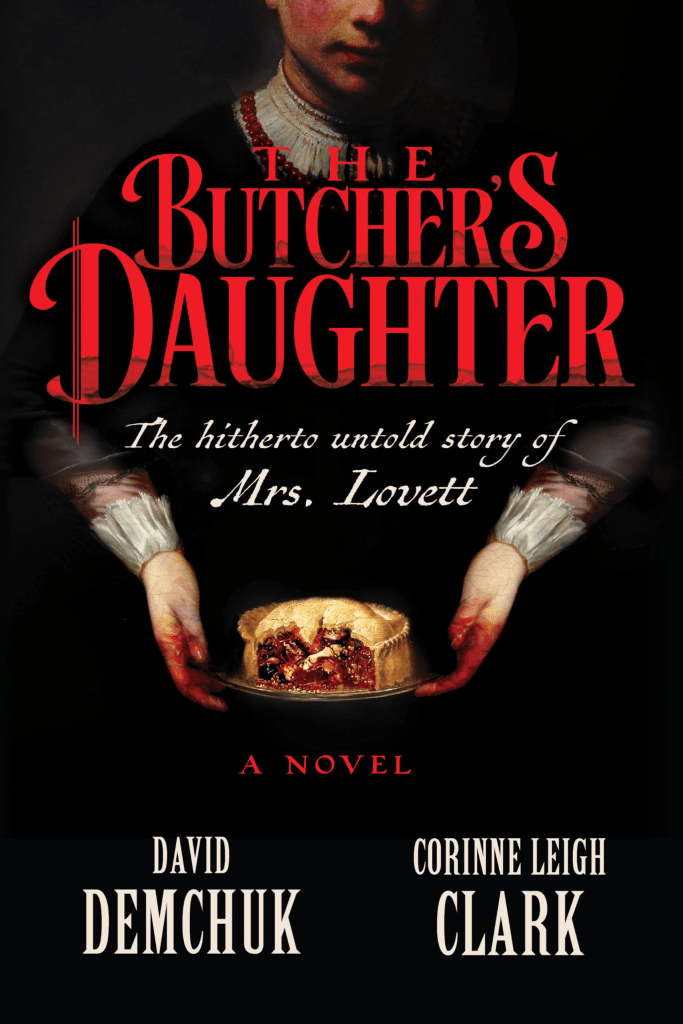

The Butcher’s Daughter: Mrs. Lovett’s PR Disaster, Now With More Letters

Demchuk and Clark team up under Soho’s Hell’s Hundred imprint for a Victorian gut-punch told as a corkboard of artifacts. The hook is deliciously lurid: a journalist sniffing around St. Anne’s Priory for the true history of Mrs. Lovett, yes the “meat pies” Mrs. Lovett, with the tale unspooling through a seized dossier of letters and documents. The book doubles down on epistolary collage, “an assembly of communications and reports” that plays like sensation-fiction autopsy notes.

London, 1887. Miss Emily Gibson probes the priory while the nuns circle the wagons. A prioress collapses and a poison narrative takes hold, then starts to stink. Suspicion spreads, brass plaques are bought, threats of “deserved silence” fly, and a voice calling herself M.E. keeps slipping letters to the gate.

This is a novel about consumption in every sense. Women’s bodies, piety as performance, and who gets to carve the narrative. Even the street gutters feel complicit, “ran red at dawn,” while skins steam and nothing goes to waste. The book keeps returning to ownership of the body and voice, with “freedom and agency” foregrounded. The style is tactile and nasty in the best way: penny-dreadful grime, newspaper clippings, pleading notes, and prim pieties all sharpening each other.

By re-centering Mrs. Lovett from the margins of myth to the center of a living archive, the novel argues that canon is usually just crime scene cleanup. Faith institutions, class privilege, and press power are all implicated. The “truth” is less a reveal than a slow bacterial bloom.

Strengths: atmosphere for days, a fully committed document form, and a chorus of believable voices. The butchery passages are sickly vivid, the priory intrigue tight, and the moral rot delicious. Minor gripes: the collage occasionally dawdles, a few side correspondents blur together, and readers craving tidy answers may want a mop and a priest.

Originality: solid. The dossier frame makes a familiar legend feel fresh. Pacing: measured but tense, with bursts of grisly momentum. Characters: M.E., Sister Catherine, and the pit-viper Augustine are sharply drawn. Scary? More dread than jump scares, but the clinical gore and moral chill do the job.

Recommended for: Readers who like their historical horror with blood under the fingernails, devotees of penny-dreadful vibes, archivists who enjoy messy truths, and anyone who thinks theology pairs nicely with a hot pie and a guilty conscience.

Not recommended for: Vegetarians of the imagination, devotees of tidy moral accounting, readers who faint at the words “offal” and “catgut,” and anyone who insists nuns never lie, scheme, or pass notes through a priory gate.

Published May 20, 2025 by Hell’s Hundred

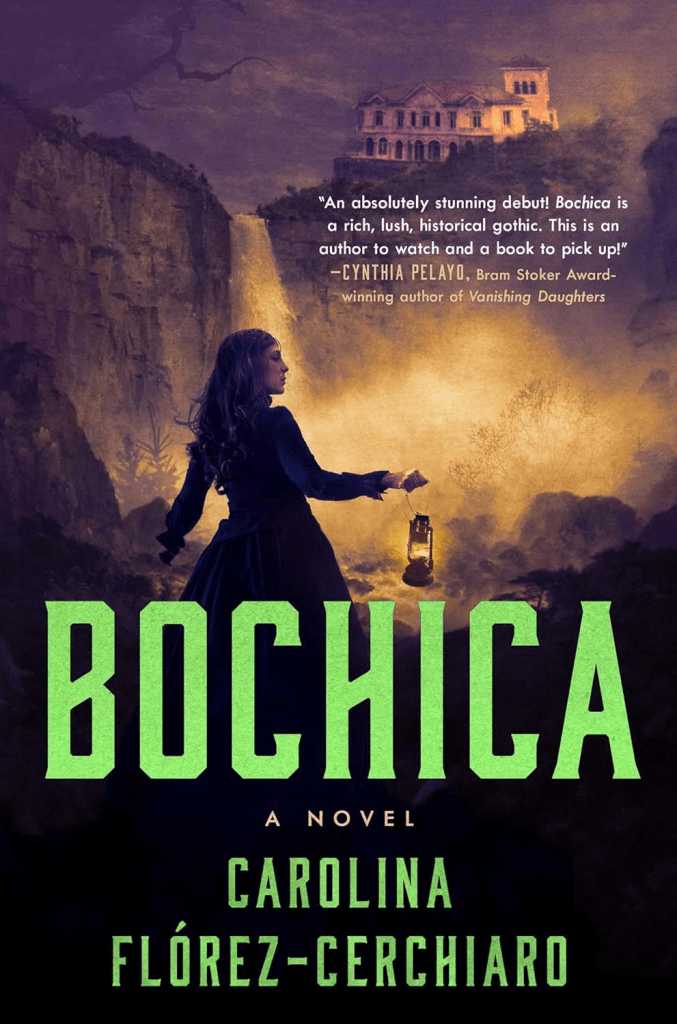

Bochica: Bogotá Gothic With Extra Incense And Side-Eye

Flórez-Cerchiaro is a Colombian writer from Medellín who blends history with the supernatural and centers marginalized voices. She drinks her coffee black and her fiction bendy. That cocktail shows up on every page here.

Bogotá, 1936. Antonia, a sharp-tongued schoolteacher drafted into Catholic catechism duty, is suffocating under nuns, patriarchy, and incense that smells like a graveyard. Her family’s old mountain manse by El Salto del Tequendama has been reborn as a luxury hotel, which is about as comforting as a smile from a vulture. Nightmares, red-eyed apparitions, and her mother’s journals drag her back to that house to confront what the hell happened.

This is Colombian Gothic soaked in folk horror. The book puts Catholic control and misogyny on blast, then braids in Muisca cosmology and talismans, with the condor and the legend of Bochica hovering like a judge in the clouds. The house itself reads like a shrine and a trap. It’s about who gets to define evil, and what belief can excuse.

On the craft side, the book is original enough to feel alive without pretending it reinvented the altar. The blend of Andean myth and Spanish Catholic terror gives the familiar haunted-house spine a new pulse, even when you can see a few beats coming. The pacing lingers in schoolroom skirmishes and catechism power plays, then tightens once we return to the cliffside hotel and the family journals start whispering. Antonia’s voice carries chapters by sheer will; Madre Asunción smiles like a splinter; Estela’s pages add grit and grief. Some side characters waft by like candle smoke and never quite condense. The scares mostly ride on oppressive mood and ritual stink rather than gotcha shocks, with one red-eye encounter that actually bites. Atmosphere and moral unease do the heavy lifting, which is the novel’s superpower and also its ceiling.

The book’s real knife isn’t the ghost; it’s the institutions. Nuns weaponize fear, men memorialize their own delusions in concrete, and myth gets domesticated into décor until it bites back. Flórez-Cerchiaro keeps asking whether evil is a demon, a doctrine, or just the rot we lovingly paint over. When the condors lift off that mural, you feel the argument: liberation isn’t neat, and faith without accountability is a predator.

Strengths: luscious sense of place, decolonial myth engine, a heroine who questions everything, and a house that feels alive. Critiques: the prose occasionally luxuriates when it should lunge, the mystery telegraphs a few beats, and the ending asks you to forgive some melodrama. Still, it’s a competent, enjoyable ride.

Verdict: Good. Not a banger, but distinctive enough to recommend.

Recommended for: Folks who like their horror humid, Catholic, and full of condors; readers who collect haunted-house blueprints and indigenous myths like trading cards; anyone who thinks a hotel opening is the perfect time to confront generational doom.

Not recommended for: People allergic to slow burns, tidy exorcisms, or stories where the scariest monster might be a smiling cleric with a syllabus. Also, if murals coming to life make you squeak, maybe sit this one out.

Published May 13, 2025 by Atria

The Man Made of Smoke: Fog, Guilt, And A Hot Dog You Will Regret Forever

Alex North, British purveyor of upscale creep, is best known for mashing crime fiction with the uncanny. Think polished page-turners like The Whisper Man and The Shadows, then imagine him cranking the fog machine and muttering about guilt.

The book opens at a motorway rest stop where a grim stranger drifts through the food court muttering “Nobody sees, and nobody cares,” before Very Bad Things follow. Years later, therapist Daniel Garvie comes home after his father’s death and gets tangled in old violence, a notorious child-killer dubbed the Pied Piper, and the true-crime circus that commodified it.

This is a book about complicity. The repeated mantra about not seeing and not caring is North’s whip, cracking at bystanders, media, and survivors alike. The Pied Piper becomes a myth about control and public apathy, while the island setting functions like a guilt terrarium that keeps dragging people back. The meta twist, where a bestselling account turns horror into product, makes the stomach turn in the right way.

North’s prose is clean and moody, with sharp set pieces: the rest-area sequence hums with fluorescent dread, and the later confrontation with a shattered boy is ice-cold and effective. Structure runs on the five stages of grief, which is neat on paper and occasionally pat in practice. The investigation beats feel tactile, yet the book loves explaining its own themes like it doesn’t trust you to keep up.

The novel’s nastiest question is whether spectatorship is its own small evil. The killer’s mantra lands like a slap, but the harsher sting is realizing how many adults did not look closely enough and then bought the hardcover later. That is bleak, honest, and worth the price of admission.

Strengths: tight scenes, a morally ugly mirror, and a killer with chilling ritual logic. Gripes: the middle sags, characters flatten into vehicles for trauma speeches, and the reveal trail leans on coincidence. The voice can feel like therapy homework stapled to a police file. Scary? Uneasy more than pants-ruining. The burned-body imagery bites, then the book gnaws the same bone.

Originality is middling. The packaging is fresh; the core is familiar true-crime dread. Pacing is front-loaded brisk, back-half swampy. Characters show promise yet too often serve the metaphor instead of breathing.

Recommended for: Readers who like their crime fiction staring into a mirror and calling them out.

Not recommended for: Anyone expecting constant terror, or for folks allergic to novels that keep repeating the same moral until it squeaks. Also not for rest-area enthusiasts. You will never buy a hot dog again.

Published May 13, 2025 by Celadon Books

We Live Here Now: Creaky Floors, Creaky Vows, Crappy Scares

Listen up, you depraved denizens of the dark. Sarah Pinborough’s We Live Here Now is a ghost story that’s more wet fart than banshee wail. This novel wants to be a spine-chilling gothic gut-punch, but it’s more like a tepid slap from a damp dishcloth. It’s got the bones of something creepy, but the flesh is flabby, and the heart’s barely beating.

The setup’s got promise: Emily and Freddie, a couple battered by her near-death coma and his gambling addiction, move into Larkin Lodge, a creepy-ass Devon manor that’s all creaky floorboards and bad vibes. Pinborough leans hard into the “haunted house picks broken couples” angle, with the place practically licking its lips at their secrets, her infidelity, his debts, and a miscarriage that’s left them raw. Strange shit starts quick: dead ravens, phantom nails, books spelling “YOU WILL DIE HERE.” Emily’s post-sepsis brain fog makes her question if it’s ghosts or her own crumbling sanity, while Freddie’s hiding something darker than his betting app. The house’s history unravels through a dusty surgeon’s ledger, hinting at murders and betrayals that echo their own fuck-ups.

Pinborough’s prose is slick, and she nails the claustrophobia of a marriage rotting under supernatural strain. The raven’s POV (yeah, a fucking bird narrates) adds a quirky, Poe-esque touch that I kinda dug, like a nod to the grim shit you lot lap up. But the plot’s a slog. It’s 500 pages of Emily limping around, hearing scratches, and doubting herself, while Freddie’s “I’m a tortured bastard” act gets old fast. The scares are repetitive, same nail, same smell, same “is it real?” bullshit. The big reveal about the house’s curse feels like it was scribbled on a napkin during a pub brawl, and the climax? A limp noodle of a resolution that left me muttering, “That’s it?” The subplots with their cheating friends, Iso and Mark, feel like soap opera filler, and don’t get me started on the Ouija board scene that’s more Scooby-Doo than The Haunting.

It’s not a total wash. The psychological horror of Emily’s fractured mind and the house’s knack for sniffing out guilt hit the mark for fans of slow-burn dread. But for my bloodthirsty blog crew, who crave Hell House levels of terror, this is a watered-down wine cooler when you’re jonesing for rotgut. Pinborough’s done better. Behind Her Eyes had more balls. This one’s a creaky old house that forgot to lock its doors against mediocrity.

Recommended for: Couples who think moving to the sticks will fix their marriage and love a tame ghost tickle.

Not recommended for: Anybody who wants to avoid another “maybe it’s all in my head” snooze-fest.

Published May 20, 2025 by Flatiron Books

Feeders: Scrolling to Hell, One Fist Bump at a Time

Alright, you sick freaks, let’s dive into Feeders by Matt Serafini, a novel that tries to claw its way into the horror pantheon but mostly just scratches at the door like a mangy cat. This book wants to be a razor-sharp commentary on social media’s dark underbelly, but it’s more like a dull butter knife, occasionally cutting, mostly just smearing the mess around.

The story follows Kylie Bennington, a college kid obsessed with climbing the ranks of MonoLife, a fictional app that’s basically TikTok on steroids, where users chase clout by posting increasingly depraved content. It’s Black Mirror meets The Purge, but with less brains and more blood. Kylie and her pal Erin get sucked into a vortex of viral stunts, from petty pranks to straight-up murder, all to keep the fist-bump notifications rolling. The app’s anonymity fuels a cesspool of voyeurism, and soon Kylie’s filming suicides, stabbings, and worse, all while dodging a shadowy figure called Mister Strangles. Sounds juicy, right? Well, hold your guts, it’s not as tasty as it seems.

Serafini’s got the right idea: social media’s a horror show, amplifying our worst impulses for likes and follows. The early chapters nail this, with Kylie’s desperation for relevance feeling like a punch to the soul. Her spiral from wannabe influencer to full-on sociopath is chilling, especially when she’s justifying atrocities for clout. But the book stumbles hard in execution. The pacing’s a mess, too many repetitive scenes of Kylie scrolling, filming, or arguing with her equally shallow friends. The horror elements, like the creepy emoji masks and gore-soaked livestreams, start strong but get numbed by overkill. By the time we hit the MonoLife Retreat (a culty influencer orgy that should’ve been the climax), it’s just a chaotic blur of blood and bad decisions.

The characters are another sore spot. Kylie’s a believable monster, but everyone else (Erin, Simon, Duc) feels like a cardboard cutout with a smartphone. The dialogue’s snappy but often veers into try-hard territory, like a Reddit thread come to life. And the supernatural hints (what’s with that throbbing back sore?) fizzle out, leaving a plot that’s more splatter than substance. Serafini’s clearly got chops. His prose can be viciously vivid, but Feeders feels like a rough draft that needed a meaner editor to trim the fat and sharpen the scares.

It’s not a total dumpster fire. The satire bites when it lands, and the gore’s grotesque enough to satisfy the splatter freaks. But this is ultimately a lukewarm shot of whiskey when you’re craving moonshine. It’s got the vibes but not the venom.

Recommended for: Social media addicts who jerk off to their follower count and think Hostel was a documentary.

Not recommended for: Anyone who likes their horror with a side of depth or a plot that doesn’t trip over its own entrails.

Published May 20, 2025 by Gallery Books

Leave a comment