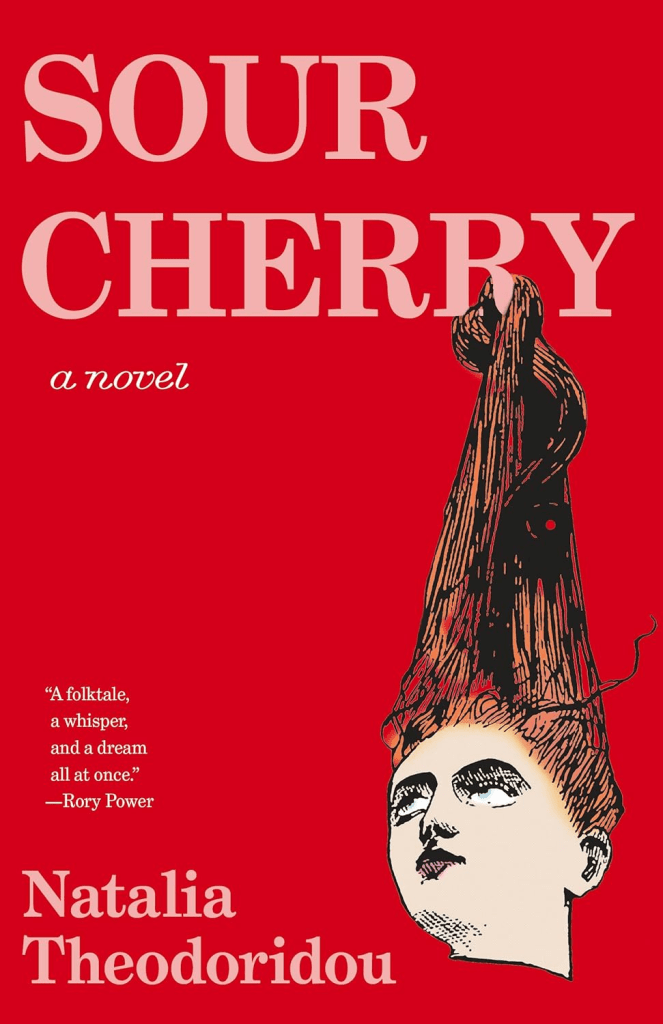

Alright, you horror-loving freaks, buckle up. Natalia Theodoridou, a queer and transmasculine Greek writer with roots sprawling across Georgia, Russia, and Turkey, has been slinging dark, weird tales for years, their work popping up in joints like The Kenyon Review and Strange Horizons. They’ve got a World Fantasy Award for Short Fiction under their belt (2018, no big deal) and a knack for stories that twist your gut while whispering cosmic unease in your ear. Their background in media and cultural studies bleeds into their fiction, giving it a layered, almost academic edge that doesn’t feel like it’s trying to impress your college professor. Sour Cherry, their debut novel, is a reimagining of the Bluebeard myth, and it’s as if Theodoridou took a rusty scalpel to the fairy tale, carved out its heart, and stitched it back together with threads of gothic menace and feminist rage. Let’s dive into this blood-soaked cherry pie and see if it’s worth the mess.

Sour Cherry unfolds in a claustrophobic apartment where a mother narrates a fractured fairy tale to her child, weaving a story that’s both a confession and a warning. The tale spirals into a gothic labyrinth of a manor house, where Agnes, a wet nurse, arrives to care for a mysterious child in a decaying estate ruled by the enigmatic Lord Malcolm. The narrative toggles between the mother’s present-day urgency and Agnes’s past, a world of blighted crops, spectral women, and a creeping sense that something is very wrong with the house and its inhabitants. It’s a story about survival, betrayal, and the stories we tell to keep ourselves sane when the walls are closing in.

This is not a mere retelling of Bluebeard; Theodoridou guts it and hangs its entrails out to dry. The core theme is the cyclical nature of abuse, how it festers, repeats, and traps its victims in narratives they can’t escape. The mother’s story to her child is a desperate attempt to break that cycle, to warn without dooming. It’s feminist as hell, not in a preachy way but in its raw, unflinching look at how women are consumed by men, by stories, by their own complicity. Agnes, the wet nurse, embodies this: she’s not a wife but a “not-quite-mother,” a woman who pours herself into a child and a man who will never fully see her, her agency eroded by her own need to be needed.

Symbolism drips from every page like blood from a fresh wound. Cherries (sour, red, staining) stand in for love, loss, and the indelible marks of trauma. They’re in the mother’s lips, the ghost wives’ mouths, the land’s decay. The manor’s crumbling walls and peeling wallpaper mirror the unraveling of sanity and the fragility of the stories we tell to survive. Ghosts, those spectral women in white and red, aren’t just spooky window dressing; they’re the weight of history, the collective memory of every woman who didn’t get out. The locked rooms and forbidden doors scream Bluebeard, but Theodoridou makes them feel less like plot devices and more like metaphors for the secrets we carry in our bones. The novel’s refusal to pin down time or place, flitting between a vague past and a modern apartment, amplifies its universality: this isn’t just one woman’s story, it’s every woman’s.

Theodoridou’s prose is a goddamn symphony of lyricism and menace. It’s poetic without being precious, each sentence sharp enough to cut but soft enough to seduce. They wield language like a painter, splashing vivid images—ghosts trailing bridal veils, cherries bursting red, a house exhaling dust—that stick in your brain like a bad dream. The dual timelines (mother’s present, Agnes’s past) are woven with precision, the fairy-tale cadence of Agnes’s story clashing beautifully with the mother’s raw, urgent voice. Honestly, sometimes the poetic flourishes pile up too thick, threatening to smother the narrative’s momentum, but when it hits, it fucking hits. The dialogue is sparse but loaded, every word a landmine. Theodoridou’s ability to shift from gothic grandeur to intimate confession is an impressive tightrope walk: thrilling, dangerous, and occasionally you wonder if they’ll fall.

The novel’s structure, with its meta-narrative of storytelling, could’ve been a gimmick, but Theodoridou pulls it off by grounding it in emotional truth. The mother’s asides to her child, the ghosts’ interruptions, and the constant reframing of the tale as a “fairy tale” keep you off balance, reminding you that stories are both salvation and cage. It’s not derivative, but you can feel the ghosts of Angela Carter and Kelly Link hovering nearby, nodding approvingly. If there’s a critique, it’s that the pacing can drag in the middle, with Agnes’s sections occasionally overstaying their welcome as they linger on atmospheric dread.

Sour Cherry is a hell of a debut, a novel that takes a fairy tale older than dirt and makes it feel like it was written in fresh blood. Theodoridou’s prose is quotable as hell: “The ghosts crowd around me, their hair in my face, their hands reaching as weightlessly as my own” could be tattooed on a horror fan’s soul. The feminist lens is sharp without being didactic, exposing the horror of patriarchal control with a clarity that’s both timeless and timely. The symbolism is rich but never heavy-handed, and the emotional weight of the mother-child relationship anchors the supernatural elements in something painfully human. It’s a book that dares to be weird, to be angry, to be beautiful, and it mostly succeeds.

The middle sags under the weight of its own atmosphere, with some of Agnes’s chapters feeling like they’re treading water in a swamp of gothic imagery. The ambiguity of the ending, while thematically fitting, might frustrate readers who want a clearer resolution. And while the prose is a strength, it can tip into self-indulgence, with a few too many metaphors crowding the page. It’s not perfect, but it’s bold, and in a genre drowning in predictable slasher rehashes, that’s worth more than gold.

This is a damn fine horror novel. It’s a haunting, original take that’ll stick with you like cherry juice on your fingers. Theodoridou takes risks, and most of them pay off.

TL;DR: Sour Cherry is a gothic fever dream that rips the Bluebeard myth apart and sews it back together with feminist fury and poetic precision. It’s a debut that’ll haunt you, equal parts beautiful and brutal.

Recommended for: Weirdos who’d rather sip absinthe with Angela Carter’s ghost than slog through another zombie novel.

Not recommended for: People who think horror means jump scares and need their endings gift-wrapped with a bow.

Published April 1, 2025 by Tin House

Leave a comment