Aislinn Clarke, the mad genius behind Fréwaka, hails from Northern Ireland and has already made waves with her debut feature, The Devil’s Doorway (2018), a found-footage horror that tackled the Catholic Church’s Magdalene Laundries with a vicious snarl. Clarke’s knack for weaving Ireland’s brutal history into supernatural dread earned her praise at festivals like FrightFest, cementing her as a voice for socially conscious horror. Before Fréwaka, she directed shorts like Childer (2016), a creepy tale of infanticide, showing her love for unsettling folk vibes. As a lecturer at Queen’s University Belfast, she’s got academic chops, but her real talent lies in crafting stories that claw at Ireland’s cultural scars. Fréwaka is her sophomore feature, and it’s clear she’s doubling down on her obsession with trauma, folklore, and the ghosts of Ireland’s past, all while screaming in Irish Gaelic to make it extra defiant.

Fréwaka follows Shoo (Clare Monnelly), a palliative care worker grappling with her mother’s recent suicide, who takes a job in a remote Irish village to care for Peig (Bríd Ní Neachtain), an agoraphobic elderly woman obsessed with the Na Sídhe, malevolent faerie folk she claims abducted her decades ago. As Shoo navigates Peig’s creaky, charm-laden house and the village’s eerie locals, her own trauma begins to blur with Peig’s paranoia. Strange visions, a blood-red cellar door, and whispers of pagan rituals pull Shoo into a web of folklore and family secrets. Clarke’s film is a claustrophobic slow-burn that leans on atmosphere over jump scares, exploring Ireland’s haunted history through two women bound by pain. It’s a folk horror tale that’s as much about roots as it is about dread.

Fréwaka is a gnarled tapestry of intergenerational trauma, Irish identity, and the collision of pagan and Christian belief systems, all shot through with a feminist lens that doesn’t preach but stabs. The title, derived from “fréamhacha” (Irish for “roots”), is the film’s core metaphor: trauma as a root system, twisting through generations, strangling the present. Clarke ties this to Ireland’s history (Magdalene Laundries, famine, and Catholic repression) without spelling it out like a history lesson. Peig’s fear of the Na Sídhe mirrors the Church’s demonization of women, while Shoo’s urban, modern outlook clashes with rural superstition, reflecting Ireland’s uneasy shift toward progress.

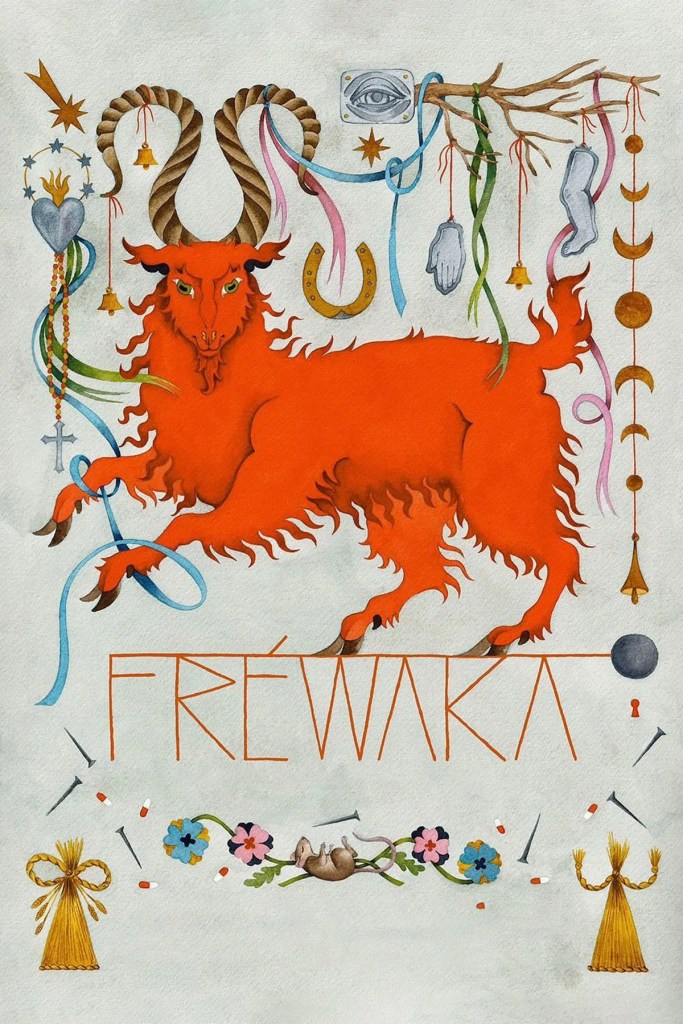

Symbolism is thick but never heavy-handed. The red cellar door, festooned with pagan charms, is a portal to the Otherworld and a stand-in for buried shame. Covered mirrors and fairy trees draped in trinkets evoke a world where the supernatural is mundane, while a glow-in-the-dark Virgin Mary statue mocks Catholic solace. Narayan Van Maele’s cinematography is a masterclass in restraint, using tight close-ups and shadowy daylight to trap us in Shoo’s unraveling psyche. The house itself, with Nicola Moroney’s decrepit production design, feels alive, its rot a visual echo of Ireland’s unhealed wounds.

Clarke’s writing is sparse yet poetic, leaning on Irish Gaelic for authenticity and lyricism. Dialogue crackles with tension. Peig’s matter-of-fact paranoia versus Shoo’s weary skepticism, but it’s the silences that scream. Philosophically, the film wrestles with how nations and individuals bury pain, suggesting that ignoring trauma only feeds the faeries. Culturally, it’s a love letter to Irish storytelling, reclaiming folklore from Hollywood’s leprechaun schlock while exposing the patriarchy’s stranglehold.

Fréwaka is a triumph of atmosphere and performance. Its strengths lie in its daring premise and execution. Clarke’s fusion of Irish folklore with real-world horrors, such as Magdalene Laundries and forced marriages, is fresh as hell, sidestepping the tired “outsider stumbles into cult” trope. Monnelly and Ní Neachtain are electric, their prickly chemistry grounding the supernatural in raw emotion. Shoo’s pill-popping anxiety and Peig’s whip-scarred back make them flawed, human, and unforgettable. The sound design, courtesy of Die Hexen’s industrial-folk score, is a nightmare lullaby that burrows into your skull. Visually, the film’s subtle imagery, a goat in ritual garb, a reflected crucifix in Shoo’s eyes, delivers deep fucking chills.

But here’s where I sharpen my axe. The pacing is deliberate… very deliberate, even for a patient viewer like me. There may be too many long shots of Shoo wandering that feel like filler. At 103 minutes, it could lose 15 and hit harder. The supporting cast, like Shoo’s partner Mila, feels tacked on, their arcs fizzling out like wet firecrackers. Originality-wise, it’s mostly a home run, but echoes of The Wicker Man and A24’s slow-burn aesthetic (think Midsommar) creep in, especially in the climactic procession. The horror is unnerving but rarely terrifying; it’s more psychological than visceral, which suits my taste but might leave some yawning. The writing occasionally stumbles. Some folklore details, like the Na Sídhe’s motives, are vague, leaving gaps where clarity could amplify dread. Still, Clarke’s vision is so singular that these flaws don’t gut the film, just bruise it.

Character-wise, Shoo and Peig carry the weight, but their backstories, while compelling, unfold too slowly, testing patience. The horror’s strength is its ambiguity. Is it faeries or madness? But it leans so hard into this that the payoff feels elusive. Yet, for every misstep, there’s a moment of brilliance, like Peig’s haunting monologue about the Otherworld, that makes you forgive the slog. Fréwaka isn’t flawless, but it’s got the balls to try something weird and meaningful, and that’s more than most horror flicks can say.

Ultimately, this film is a goddamn treat. Its bold premise feels like a fresh wound, and Clarke’s atmospheric direction is a masterstroke. The performances and production design are top-tier, and the thematic depth hits my sweet spot. But the sluggish pacing and occasional reliance on familiar tropes keep it from greatness. It’s not The Witch or The Wicker Man, but it’s a hell of a lot closer than most. For fans of slow-burn folk horror with cultural heft, it’s a must-watch, but don’t expect a blood-soaked banger. Clarke’s a director to bet on, and Fréwaka proves she’s got the chops to haunt us for years.

TL;DR: Fréwaka is an Irish-language folk horror that weaves trauma, folklore, and feminist rage into a creepy, if uneven, slow-burn. Stellar performances and atmosphere outweigh pacing issues for a haunting indie gem.

Recommended for: Folklore nerds who’d sell their soul to the Na Sídhe for a pint of Guinness and a creepy bedtime story.

Not recommended for: ADHD gorehounds who think Irish Gaelic is just drunk English.

Director: Aislinn Clarke

Writer: Aislinn Clarke

Distributor: Shudder

Released: March 20, 2025

Leave a comment