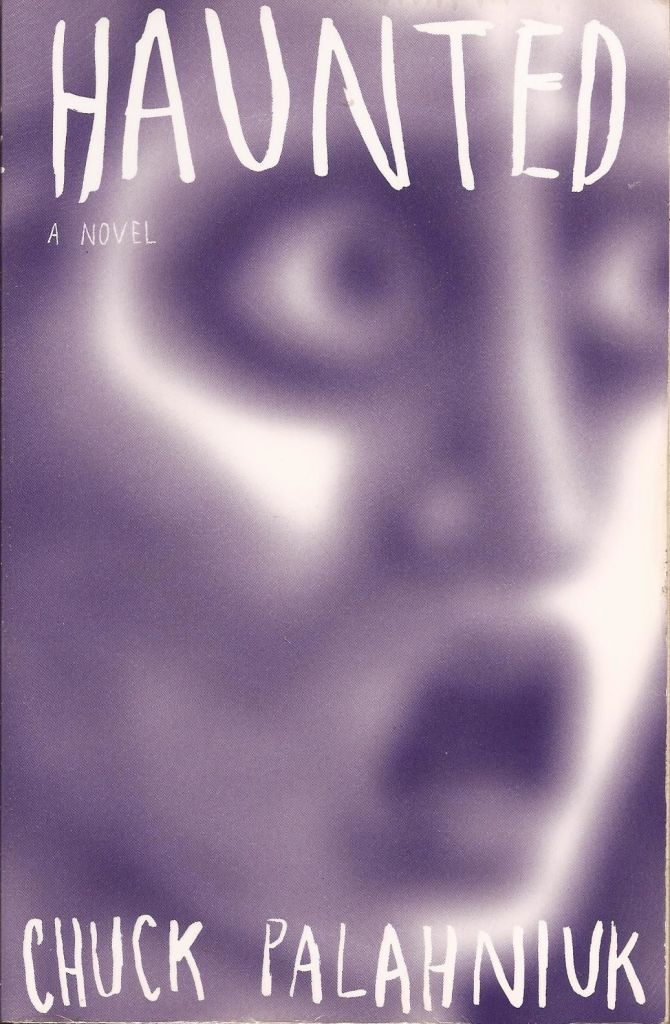

Chuck Palahniuk has spent his career dancing on the razor’s edge of transgression, turning the grotesque into grotesque poetry. Known best for Fight Club, Palahniuk has built a reputation as the bard of the disaffected, an architect of narratives that revel in social decay, nihilism, and the ever-thin veneer of civility that barely contains human depravity. His works often explore themes of alienation, self-destruction, and the dark side of human desire, all wrapped in a style that combines minimalist prose with shocking imagery. If Fight Club was an anarchist’s handbook for toxic masculinity and consumerist disillusionment, Haunted is a misanthropic love letter to human monstrosity itself.

Published in 2005, Haunted is an ambitious, experimental novel masquerading as a collection of interwoven short stories. The overarching premise is simple: a group of writers answers an advertisement for a secluded writer’s retreat, only to find themselves trapped in an increasingly nightmarish scenario. Led by the enigmatic Mr. Whittier, the group of misfits—each given nicknames like Comrade Snarky, Saint Gut-Free, and Mother Nature—gradually descends into savagery, sabotaging their own survival for the sake of crafting the ultimate horror story. Structured as a blend of poetry, short stories, and the novel’s central narrative, Haunted functions both as an anthology of individual nightmares and a social experiment in collective degeneration. Each participant has a story to tell—often a horrifying or satirical commentary on modern society—while the novel’s overarching plot serves as a brutal satire of human ambition and self-sabotage.

At its core, Haunted is a commentary on the desperate lengths people will go to for fame, validation, and meaning. Palahniuk constructs a narrative where people are willing to starve, maim, and even kill for a good story, a metaphor for the extremes of artistic sacrifice and the entertainment industry’s commodification of suffering.

One of the most potent symbols in the novel is food—or rather, the lack thereof. As the characters slowly starve, their physical deterioration parallels their moral collapse. The fact that they could leave at any time but choose to stay speaks to the self-destructive allure of storytelling as both salvation and curse. The novel suggests that humanity’s true horror isn’t supernatural—it’s our own selfishness, vanity, and willingness to manufacture suffering for spectacle.

There’s also a persistent motif of bodily horror, best exemplified in the infamous story “Guts,” a tale so viscerally disturbing that it reportedly caused readers to faint at public readings (you keep hearing these stories about books and films every few years). This bodily disintegration throughout the novel mirrors the characters’ psychological disintegration, reinforcing Palahniuk’s belief that the human body and mind are equally fragile and grotesque.

Palahniuk’s signature prose is on full display in Haunted—terse, punchy, and brutally efficient. His penchant for repetition and staccato phrasing gives the novel an almost hypnotic rhythm, one that draws the reader into its sickly fascinating horror. However, while this style works brilliantly in shorter works like Fight Club or Choke, its effectiveness in Haunted is more debatable. The novel’s disjointed structure means that just as one story grips the reader, it is abruptly interrupted by another, breaking narrative momentum.

Moreover, Haunted leans heavily on shock value. There is a difference between horror that lingers and horror that assaults, and Haunted often chooses the latter. While Palahniuk has always wielded shock as a tool for commentary, here it sometimes feels like an end unto itself. Stories like “Guts” succeed because they combine visceral horror with tragic irony, but others, like “Exodus” or “Hot Potting,” feel gratuitous, as though they exist solely to test the reader’s tolerance for disgust rather than to serve a deeper narrative purpose.

Despite its excesses, Haunted is undeniably compelling. Palahniuk’s vision of human nature—depraved, desperate, and darkly comedic—remains as relevant today as it was 20 years ago. The novel’s satirical edge cuts deep, particularly in its critique of the media and reality television’s exploitation of tragedy. The individual stories, while uneven, include some of Palahniuk’s most memorable work. “Guts” is a modern horror classic. “Slumming” offers a brilliant critique of privilege and the romanticization of suffering. “The Nightmare Box” feels like a lost episode of The Twilight Zone, oozing existential dread. When Haunted works, it really works.

The novel’s biggest issue is its length and repetition. What begins as an intriguing social experiment devolves into a series of escalating grotesqueries, each trying to outdo the last. The characters, while conceptually interesting, remain largely one-dimensional, existing more as caricatures than fully fleshed-out people. Their self-imposed suffering becomes exhausting rather than engaging.

Additionally, the novel’s structure—jumping between the main plot, individual stories, and poetry—makes for a frustratingly uneven reading experience. While some of these interruptions are masterfully placed, others feel like distractions that detract from the overarching narrative’s impact. Finally, while Palahniuk’s critique of media culture is insightful, it sometimes feels heavy-handed. Haunted doesn’t so much trust the reader to grasp its themes as it beats them over the head with them. Subtlety is not Palahniuk’s strong suit, and while that works in his best novels, Haunted often feels like it’s shouting its message rather than letting it unfold naturally.

Two decades later, Haunted remains one of Chuck Palahniuk’s most polarizing works. It is equal parts brilliant and exhausting, insightful and indulgent. At its best, it delivers some of the most unsettling and thought-provoking horror of the 21st century. At its worst, it becomes a test of endurance rather than a rewarding literary experience. For readers who revel in the grotesque and can stomach the darkest aspects of human nature, Haunted is a must-read. For those looking for a more cohesive, emotionally resonant Palahniuk novel, Fight Club or Invisible Monsters might be a better entry point.

Ultimately, Haunted is an ambitious, flawed, and unforgettable novel—a book that, love it or hate it, refuses to be ignored.

Published June 21, 2005 by Vintage

Leave a comment