So, you decided to check out Tarot, hoping for a creepy, spine-tingling horror flick that would make you regret every late-night dabble with the occult. Well, I bet you regret it, because what you get instead is a clunky mess of jump scares, facepalming character decisions, and a storyline that’s about as coherent as a drunken tarot reading. I watched the fucking trailer, why did I force myself to watch this? What I do for my (lack of) readers…

Tarot, directed by Spenser Cohen and Anna Halberg (Moonfall, Extinction, Expendables 4… basically directors if cinematic masterpieces), follows a group of college kids who think it’s a brilliant idea to mess with a creepy old deck of tarot cards they find in the basement of a rented mansion. Unsurprisingly, this boneheaded move unleashes a curse that leads to their untimely, and predictably ridiculous, deaths. Each character gets a tarot card that somehow predicts their doom in the lamest way possible.

We’ve got a hell of a cardboard cast for you. First up, we have Haley (Harriet Slater), our resident tarot enthusiast who should’ve known better. She’s nursing a broken heart from her recent breakup with Grant (Adain Bradley) and dealing with her mom’s death, so obviously, dabbling with cursed cards seems like the perfect distraction… girl needs some Jesus in her life. Then there’s Paxton (Jacob Batalon), whose main role is to provide comic relief that’s about as funny as a root canal. The rest of the crew – Paige (Avantika), Elise (Larsen Thompson), Madeline (Humberly González), and Lucas (Wolfgang Novogratz) – are as memorable as the last tarot reading you had at a county fair.

Of the biggest problems with Tarot is its utter reliance on jump scares. It’s like the directors set a timer to go off every ten minutes to remind them to throw in a loud noise and a sudden movement. The suspense is non-existent because you see every scare coming a mile away. And the deaths? Let’s just say, if you’re into off-screen kills and cutaways right before anything interesting happens, you’re in for a treat. Gotta love PG-13 (not everyone can make The Ring). One character gets sawed in half by a demonic magician, but don’t worry, you won’t actually see it – just a quick cut to another scene. How’s that for tension?

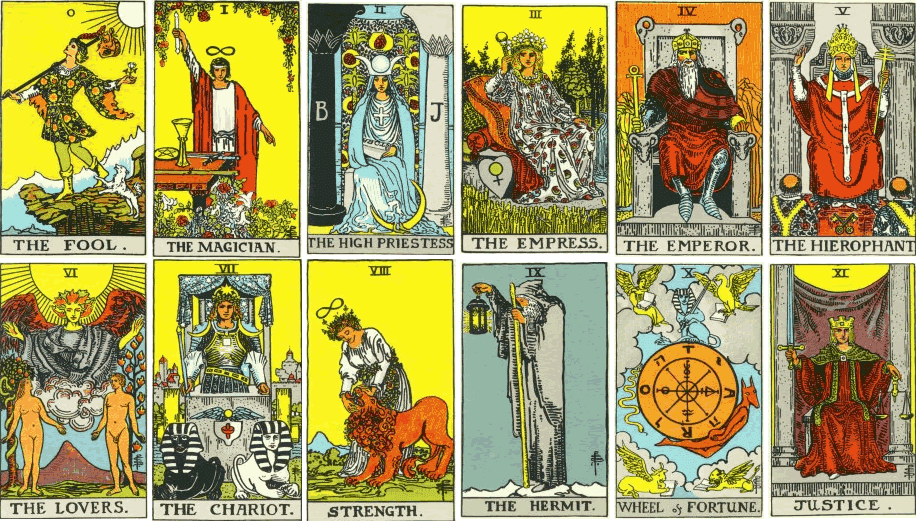

Now, let’s talk about the only decent thing in this film: the creature design. The tarot card villains, like The Fool, The Magician, and The High Priestess, actually look pretty cool. Credit where it’s due, the art department did a good job here. Unfortunately, these creepy-cool designs are wasted on a film that doesn’t know how to use them. The lighting is so bad you can barely see them half the time, and when you do, it’s usually accompanied by yet another lazy jump scare.

The screenplay, based on Nicholas Adams’ 1992 novel Horrorscope, feels like it was written by someone who got bored halfway through and decided to copy-paste from a list of horror clichés. The dialogue is cringeworthy, with characters spouting lines that I hope no real human would ever say. They make decisions that are so idiotic you’ll be rooting for the tarot monsters to put them out of their misery just so you don’t have to listen to them anymore.

At 92 minutes, Tarot manages to feel both rushed and painfully slow. The editing is choppy, with scenes jumping around in a way that makes it hard to follow what’s happening – not that you’ll care much. The film spends an eternity on pointless exposition and then speeds through the supposedly scary bits. It’s a masterclass in how not to build tension.

The cast, especially Jacob Batalon, deserves better. Batalon’s Paxton is stuck delivering terrible jokes and acting like he’s in a different movie entirely. Harriet Slater tries to bring some depth to Haley, but it’s a losing battle against the script. Avantika is utterly wasted here, blending into the background like a piece of old wallpaper.

Tarot is a frustratingly bad movie that squanders its only good element – the creature design – on a plot that’s been done to death and characters you won’t remember five minutes after the credits roll. If you’re looking for a horror movie that will actually scare you, keep looking. If you want to see cool monster designs, just Google the images and save yourself the trouble of sitting through this snooze-fest.

In summary, Tarot is a horror flick that should’ve stayed in the deck. It’s a predictably bad, jump-scare-riddled, poorly written mess that fails to deliver on any front except for a few cool-looking creatures. Maybe next time, the filmmakers will draw a better hand.

But, hey, if you want to learn a bit more about the tarot, keep reading!

Director: Spenser Cohen, Anna Halberg

Writer: Spenser Cohen, Anna Halberg

Released May 3, 2024

While I tend to be a pretty skeptical person, at heart I want to believe in the mystical and supernatural. So, I seek it out. As you may have noticed with my review of Silver Nitrate I love investigating the historical roots that can inspire horror. Relevant to this film, the origins of tarot cards are quire interesting, beginning in the 15th century, rooted deeply in the social and cultural fabric of Renaissance Europe.

Tarot cards, originally known as “tarocchi,” first appeared in northern Italy around the 1440s. These cards were not intended for divination initially but were used for playing a group of card games that are still played today in some parts of Europe. The structure of these decks was somewhat similar to the modern tarot. The decks typically comprised 78 cards, split into the major arcana (22 cards) and the minor arcana (56 cards). The minor arcana resembled contemporary playing cards with four suits. In tarot, these suits are typically cups, swords, wands (or staves), and coins (or pentacles), each containing 14 cards—ten numbered cards and four court cards (king, queen, knight, and page).

The major arcana consisted of allegorical figures, each illustrated with symbolic imagery reflecting various themes like strength, justice, and the fool. These figures weren’t just arbitrary but were deeply infused with the medieval iconography that resonated with the cultural and philosophical preoccupations of the era.

One of the earliest and most significant tarot decks was created for the Duke of Milan, Filippo Maria Visconti, and his successor Francesco Sforza. These decks, known collectively as the Visconti-Sforza tarot, are among the oldest surviving tarot cards and show exquisite artistic detail, a hallmark of the craftsmanship and artistic abilities of the time. Painted by Bonifacio Bembo and other artists of the Milanese court, these cards were luxuriously crafted with gold leaf, indicative of their role as aristocratic status symbols rather than mere playing cards.

The iconography of the early tarot is often linked to the Christian morality and the Renaissance’s rediscovery and reinterpretation of classical philosophy, art, and science. The cards included themes and characters from Christian allegories, medieval courts, and classical myths, reflecting the complex interplay between various cultural streams.

From Italy, the use of tarot cards spread to other parts of Europe. The French tarot, which used the cards for a different set of game rules, became particularly popular. As the cards spread, they evolved into various regional patterns. Some of these, like the Tarot de Marseille, which appeared in the 17th century, would become standards for later occult interpretations.

The transition of tarot cards from simple playing tools to objects of occult and mystical significance occurred during the late 18th and early 19th centuries. This shift is largely attributed to the work of several key figures and a changing European intellectual environment that was increasingly open to esoteric and mystical ideas.

The most pivotal figure in this transition is Antoine Court de Gébelin (1725–1784), a French clergyman, scholar, and Freemason. In 1781, de Gébelin published a massive study of the tarot in his work, “Le Monde Primitif,” in which he asserted that tarot cards were not merely playing cards but were, in fact, mystical Egyptian hieroglyphs in disguise. According to de Gébelin, these cards preserved ancient universal wisdom and held the secrets of the universe, which had been brought to Europe by traveling gypsies from Egypt.

De Gébelin’s theories were speculative and not based on any historical evidence, but they captivated the imagination of the public and scholars alike. He claimed that the tarot deck encoded ancient wisdom and could be used for divination, to uncover hidden knowledge and divine the future. This was the first serious proposal that tarot cards could be used for esoteric purposes, rather than entertainment.

Another significant contributor to the esoteric tradition of tarot was Jean-Baptiste Alliette, better known by his pseudonym, Etteilla. He was a Parisian occultist who was the first to create a comprehensive method of tarot divination, released in several works from 1783 onwards. Etteilla redesigned the traditional tarot to align with his own interpretations and occult beliefs, creating one of the first tarot decks specifically designed for divinatory purposes. His deck, along with its accompanying book of instructions, laid down many of the conventions still used in tarot readings today.

Etteilla’s modifications included the introduction of astrological attributions to the cards, the elements, and other esoteric correspondences, such as the four humors and the Hebrew alphabet, which were not part of the original tarot symbolism.

The late 18th century and throughout the 19th century saw a resurgence in interest in the occult, which played a critical role in the transformation of tarot. This period, often referred to as the Occult Revival, saw tarot being increasingly folded into the broader fabric of Western esotericism. Occult societies such as the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn, which emerged in the late 19th century, incorporated tarot into their rituals and practices. Members such as Arthur Edward Waite and Aleister Crowley, both influential figures in their own right, developed new tarot decks that deeply embedded the cards in the Kabbalistic, alchemical, and Christian mystical traditions.

By the time the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn got involved, tarot had been thoroughly integrated into the mystical and occult traditions of the West. The Golden Dawn developed complex connections between the tarot cards, astrology, Hebrew letters, and the paths on the Kabbalistic Tree of Life, crafting a comprehensive framework that remains influential among modern practitioners.

The development of occult tarot during the 19th century represents a significant evolution in the history of tarot cards, as they were increasingly intertwined with esoteric theories and mystical philosophies. This period saw several key figures and movements redefine tarot from a simple card game to a profound tool for divination and self-discovery.

One of the most influential figures in this transition was Alphonse Louis Constant, better known by his pseudonym, Eliphas Lévi. A French occultist and ceremonial magician, Lévi was pivotal in integrating the tarot with the Jewish mystical system of Kabbalah. In his seminal works, such as “Transcendental Magic, its Doctrine and Ritual” (1854-1856), Lévi proposed that the tarot symbols are directly related to the Hebrew alphabet and the Kabbalistic Tree of Life, with each card corresponding to a specific path or sephira on the Tree.

Lévi’s ideas were revolutionary because they provided a framework that extended the interpretive possibilities of tarot beyond simple fortune-telling, suggesting that the cards could be used as keys to understanding esoteric truths about the human condition and the workings of the cosmos. His association of the Major Arcana cards with the Hebrew letters laid the groundwork for the tarot’s later developmental stages within occult circles.

The late 19th century saw the rise of the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn, an organization that was to have a profound impact on the development of the modern occult tradition, including tarot. Founded in 1888 by William Wynn Westcott, Samuel Liddell MacGregor Mathers, and William Robert Woodman, the Golden Dawn synthesized elements of Freemasonry, Rosicrucianism, Theosophy, and various other esoteric doctrines.

Arthur Edward Waite, a member of the Golden Dawn, is particularly notable for his development of the Rider-Waite-Smith Tarot deck in 1909, which was illustrated by Pamela Colman Smith, also a member of the Order. Waite’s deck was one of the first to include detailed pictorial images for the Minor Arcana cards, not just the Major Arcana. This innovation allowed for more nuanced interpretations and made the tarot more accessible to the general public, not just occult practitioners.

The imagery of the Rider-Waite-Smith deck incorporated many of Lévi’s and the Golden Dawn’s symbolic correlations but was designed to be somewhat more ecumenical in its spiritual symbolism. It remains one of the most popular and influential tarot decks in the English-speaking world.

Another key figure in the development of occult tarot was Aleister Crowley, also a former member of the Golden Dawn, who later developed his own magical system and philosophy. Crowley created the Thoth Tarot deck, painted by Lady Frieda Harris. This deck was filled with symbolic imagery that drew from astrology, alchemy, and the Kabbalah, reflecting Crowley’s belief in the tarot as a tool for spiritual evolution and enlightenment. The Thoth deck, published posthumously in the 1960s, is renowned for its intricate artwork and complex interpretative depth.

The development of occult tarot in the 19th and early 20th centuries transformed tarot cards into a profound system of symbols capable of providing deep psychological insights and spiritual guidance. This period established many of the foundational concepts and methodologies still used in tarot practice today, embedding the cards deeply within the Western esoteric tradition.

Leave a comment