Silvia Moreno-Garcia is a Mexican-Canadian author and editor known for her work in a variety of genres, including fantasy, science fiction, horror, and historical fiction. Born in Baja California, Mexico, she moved to Canada as a young adult. Moreno-Garcia’s diverse body of work often draws on her Mexican heritage, blending elements of Mexican culture, folklore, and mythology with her narratives.

Moreno-Garcia’s writing is characterized by its richly imagined worlds, complex characters, and intricate plots. She has a talent for weaving elements of the supernatural and the fantastic into her stories in a way that feels both fresh and deeply rooted in folklore.

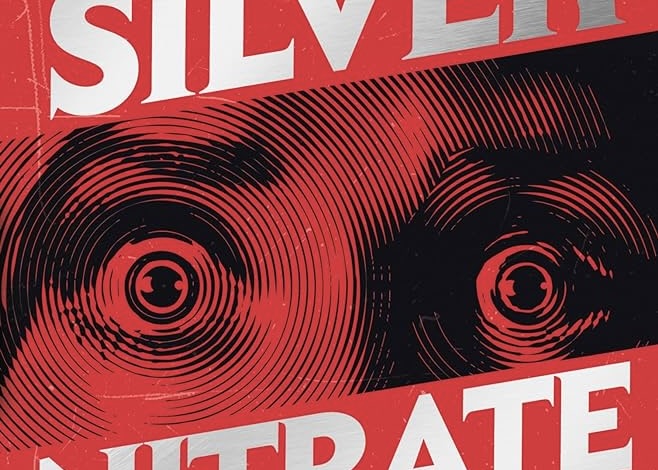

Dive into her latest thriller, Silver Nitrate, and you’re in for a rollercoaster ride that’s part ghost train, part cinematic time machine, whisking you away to 1993 Mexico City—minus the questionable fashion choices. Imagine, if you will, Montserrat, a sound editor with more skills than a Swiss Army knife but somehow still flying under the radar, reflecting Moreno-Garcia’s homage to her own mother’s struggle in the machismo-infested radio world of yesteryears. Then there is Montserrat’s buddy Tristán, who’s essentially the Brad Pitt of soap operas, if Brad had a penchant for the paranormal and a bit less luck.

Together, they stumble into the world of Abel Urueta, a director whose films are so cursed, they make the set of Poltergeist look like a walk in the park. His long lost project, Beyond the Yellow Door, is a cocktail of silver nitrate and dark arts, shaken not stirred, with a splash of Nazi occultism courtesy of Wilhelm Ewers.

Moreno-Garcia doesn’t just throw her characters into this haunted house of a plot; she sets the whole thing against the backdrop of a Mexico City that’s as vibrant and complex as a mole sauce, with a side of socio-political unrest. The novel tickles real-life horrors like fascism and racism with a paranormal feather, because sometimes a ghost story is more than just a ghost story. But don’t expect a documentary; this is more ‘spooky history class meets movie night’. Also, there’s a deep dive into film and occult trivia that didn’t make the cut, because apparently, even haunted tales have a word limit. Pity, as who wouldn’t want to learn more about Nazi occultists chilling under the ice (It’s actually really interesting and scary – see the spoiler section below if your a history buff)?

Sure, the book might take its sweet time getting off the starting blocks, but once it gets going, there’s no stopping it. The second half zips along faster than a greased Chupacabra, pulling you into a whirlwind of supernatural shenanigans and historical whodunnits.

Silver Nitrate isn’t just a book; it’s a masterclass in how to blend the eerie with the eerily real, making the silver nitrate film and the gritty streets of Mexico City characters in their own right. Moreno-Garcia serves up a story that’s as rich and layered as the city it’s set in, proving once again that she’s not just playing in the horror sandbox—she’s building castles with a moat full of monsters.

In a nutshell, Silver Nitrate is Moreno-Garcia’s love letter to those of us who geek out over horror, history, and the magic of movies. It’s a tale that reminds us why we’re afraid of the dark, all while making us wish we could join Montserrat and Tristán for just one night of haunted hijinks. So, grab your popcorn (and maybe a protective talisman or two) and settle in for a story that’s as entertaining as it is enlightening.

Del Rey

Published July 18, 2023

I got excited reading Silver Nitrate because Silvia Moreno-Garcia clearly did her research on occultism, a subject I find fascinating. While German occultism dates back to Medieval times, one of the more interesting times was the occult revival of the late 19th to early 20th centuries. For those interested in an expanded history of this period, feel free to keep reading:

The Occult Revival in Germany during the late 19th and early 20th centuries represents a complex and multifaceted period in the history of occultism. This era was marked by a profound interest in esoteric knowledge, spiritualism, and the integration of ancient wisdom with the new scientific discoveries of the time. Two of the most significant movements emerging from this revival were the Theosophical Society and the Anthroposophical Society, alongside the development of Ariosophy, which wielded a darker influence on the political landscape of Germany.

The Theosophical Society, founded in 1875 by Helena Petrovna Blavatsky, Henry Steel Olcott, and others, was instrumental in the global spread of occult and esoteric ideas. While not a German organization per se, its influence permeated German occult circles significantly. The Society’s teachings were rooted in the synthesis of Eastern and Western philosophies, emphasizing the exploration of the mystical and occult traditions of the world, the study of comparative religion, philosophy, and science, and the investigation of unexplained laws of nature and the powers latent in humanity.

The Theosophical Society’s ideas found fertile ground in Germany, appealing to those disillusioned with conventional religious institutions and intrigued by the integration of spirituality and science. German theosophists engaged deeply with the Society’s literature, contributing to the translation and dissemination of Theosophical works, and organizing lectures and study groups across the country.

Rudolf Steiner, an Austrian philosopher, social reformer, and esotericist, initially associated with the Theosophical Society, founded the Anthroposophical Society in 1912. Steiner’s break from Theosophy was rooted in his desire to create a spiritual movement more closely aligned with Western esoteric traditions and Christian mysticism, and to apply esoteric knowledge to practical fields such as education, agriculture, and the arts. Anthroposophy, meaning “wisdom of the human being,” proposed an elaborate spiritual science that aimed to uncover the spiritual dimensions underlying the physical world. Steiner developed a unique system of thought that included concepts such as karma and reincarnation, the spiritual evolution of humanity and the Earth, and the existence of spiritual beings at various levels of reality.

The practical applications of Anthroposophical ideas led to the creation of Waldorf schools, biodynamic farming, anthroposophic medicine, and eurythmy (a form of expressive movement art). In Germany, these initiatives flourished, leaving a lasting legacy on educational and agricultural practices.

A darker strand of occultism emerged in the form of Ariosophy, developed by Guido von List and Jörg Lanz von Liebenfels. Ariosophy, blending the words “Aryan” and “Sophia” (wisdom), sought to revive ancient Germanic pagan traditions, but it was deeply entwined with nationalist and racist ideologies. List and Liebenfels posited the superiority of the “Aryan race” and combined esoteric and mystical beliefs with anti-Semitic and racist views.

List was an occultist, mystic, and nationalist who believed in the existence of a secretive, ancient Germanic priesthood called the Armanenschaft. He propagated the idea of rune magic, ancient Germanic wisdom, and a pan-Germanic revival, claiming that modern society had fallen from its ancient spiritual greatness.

Liebenfels founded the Order of the New Templars, an esoteric society that mixed Christian and pagan elements with racist doctrines. He published Ostara, a magazine that propagated his theories of racial purity and eugenics, influencing a wide readership, including, allegedly, Adolf Hitler.

The Thule Society, a secretive group formed in Germany just after World War I, plays a pivotal role in the nexus between occultism and the early Nazi movement, bridging the gap between esoteric interests and political ideology. Established in Munich in 1918 by Rudolf von Sebottendorff, the Thule Society was named after a mythical northern land in Greek legend, which was synonymous with the pursuit of ancient Aryan culture. The society was deeply infused with nationalist, anti-Semitic, and anti-communist sentiments, making it a crucible for the ideological underpinnings that would later characterize the Nazi Party.

Interestingly, the concept of the “Aryan race” has its origins in linguistic studies rather than racial science. The story begins with the recognition of similarities between European languages and those of the Indian subcontinent. In the late 18th century, Sir William Jones, a British judge, and scholar in India, proposed that Latin, Greek, and Sanskrit, the ancient language of India, had a common origin. This led to the identification of the Indo-European language family, a group of related languages spreading across most of Europe and into parts of Asia, including Iran (Persia) and the Indian subcontinent. The word “Aryan” comes from Sanskrit, where it means “noble” or “honorable” and was used by the peoples of ancient India to describe themselves and their languages. Similarly, in ancient Persia, the term was used to refer to the ethnic group who spoke Old Iranian languages and identified themselves as noble or free.

As European scholars delved into comparative linguistics and archaeology, some began to speculate about the peoples who spoke these ancient languages. The term “Aryan” was gradually extended from a linguistic label to denote a supposed racial group. The idea of the Aryans began to be romanticized in European nationalism and folklore, envisioned as a superior race of noble origins, creators of civilization, and progenitors of the European peoples.

The aforementioned theosophical movement, founded by Blavatsky, also adopted the term “Aryan” in its esoteric teachings. Blavatsky described the Aryans as a spiritually advanced people in her cosmology of root races, further detaching the term from its linguistic roots and embedding it within occult and mystical ideologies.

Of course, the most infamous appropriation and distortion of the term “Aryan” occurred in Nazi Germany. The Nazis adopted the concept of the Aryan race to construct a racial hierarchy that placed “Aryan” peoples, particularly those of Northern European descent, at the top, as the supposed master race. This perverted interpretation was used to justify horrific policies of racial purification, anti-Semitism, and genocide, leading to the Holocaust.

The Thule Society emerged from the German Workers’ Party (Deutsche Arbeiterpartei, DAP), which later evolved into the National Socialist German Workers’ Party (NSDAP), more commonly known as the Nazi Party. Its members believed in the racial superiority of the Aryan people and were dedicated to the revival of the ancient Germanic traditions, myths, and symbols they believed were linked to the Aryan race. The society mixed these racist and nationalist ideologies with a keen interest in occult practices, including astrology, mysticism, and theosophy, reflecting the broader occult revival occurring in Germany at the time.

Several members of the Thule Society were directly involved in the early development of the Nazi Party. For instance, Rudolf Hess, who would later become Adolf Hitler’s deputy, and Dietrich Eckart, one of Hitler’s early mentors, were associated with the Thule Society. Eckart, in particular, is often credited with shaping Hitler’s anti-Semitic and nationalistic views, as well as introducing him to various esoteric ideas.

The Thule Society played a role in the Munich Putsch of 1923, an early attempt by the Nazi Party to seize power. While the coup failed, it was a pivotal moment in the rise of the Nazi movement, demonstrating the willingness of its members to engage in direct action to achieve their goals. The involvement of Thule Society members in the putsch illustrates the society’s commitment to merging its esoteric and nationalist objectives with political activism.

After the failure of the Munich Putsch and as the Nazi Party began to gain traction in German politics, the importance of the Thule Society diminished. The Nazis sought to present a more unified and less overtly mystical front to gain widespread support among the German population. As a result, the explicit occultism of the Thule Society fell out of favor within the upper echelons of the Nazi Party, although the ideological and symbolic influences remained.

The relationship between the Nazi regime and occultism during the 1930s and 1940s is a subject of extensive historical interest and speculation. While the official stance of the regime was to suppress occult practices, viewing them as superstitious and potentially subversive, there was a notable fascination with the occult among some of its highest-ranking officials. This paradoxical stance reflects the complex interplay between ideology, power, and the search for legitimacy through ancient traditions. The aftermath of World War II saw a significant shift in the perception and practice of occultism within Germany, influenced by the war’s profound cultural and psychological impacts.

Heinrich Himmler, one of the most powerful men in Nazi Germany, harbored a deep interest in the occult. He was particularly fascinated by ancient Germanic paganism and the potential of occult practices to reinforce the Nazi narrative of Aryan supremacy. Himmler’s SS (Schutzstaffel) was not just a military organization but also a quasi-mystical order, with Himmler envisioning the SS as a modern incarnation of the Teutonic Knights, embodying purity, loyalty, and a mission to safeguard the Aryan race. The SS conducted research into ancestral heritage, Germanic pre-Christian traditions, and occult symbols, seeking to embed these elements into the ideological framework and rituals of the Nazi party.

The Ahnenerbe (Ancestral Heritage) was an organization founded by Himmler in 1935, dedicated to researching the archaeological and cultural history of the Aryan race. It undertook expeditions and scholarly studies aiming to find evidence of the global dominance and advanced civilization of ancient Aryan peoples. This research was intended to provide a historical and scientific foundation for Nazi racial theories, blending genuine archaeological work with esoteric speculation and pseudoscience.

The Nazi regime employed a range of symbols and rituals with occult or mystical connotations. The swastika, appropriated as the emblem of the Nazi Party, is an ancient symbol with positive meanings in many cultures. The Nazis, however, reinterpreted it as a symbol of Aryan identity and power. Other symbols, like the SS runes, the Totenkopf (Death’s Head), and the Black Sun, were integral to the iconography of the Nazi regime, embedding esoteric meanings into the visual and ritualistic fabric of Nazism.

The Occult Revival period in Germany was a time of great spiritual exploration but also of socio-political danger, as the incorporation of esoteric ideas into nationalist and racist ideologies contributed to the toxic environment that allowed the rise of Nazism. The legacy of the Theosophical and Anthroposophical Societies remains influential in contemporary spiritual and educational circles, reflecting the positive search for knowledge and understanding. While the shadow of Ariosophy serves as a reminder of the potential misuse of occult and esoteric beliefs for harmful ends, Theosophy is not exactly guilt-free, claiming nonsense like races with lower and higher levels of consciousness. The diverse outcomes of this period underscore the complex nature of the occult revival in Germany, reflecting broader themes of search for meaning, the intersection of spirituality and science, and the dark potential of misapplied esoteric wisdom.

Leave a comment